Evergrande, Ever Given, & beyond

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

In March, the Ever Given, one of the world’s largest container ships, grounded itself in the Suez Canal. In the six days that it was wedged in the Canal, it held up over 350 ships and led to widespread delays as global shipping was backlogged. At the time, I noted that the search for efficiency had led to an exposure to diseconomies of scale.

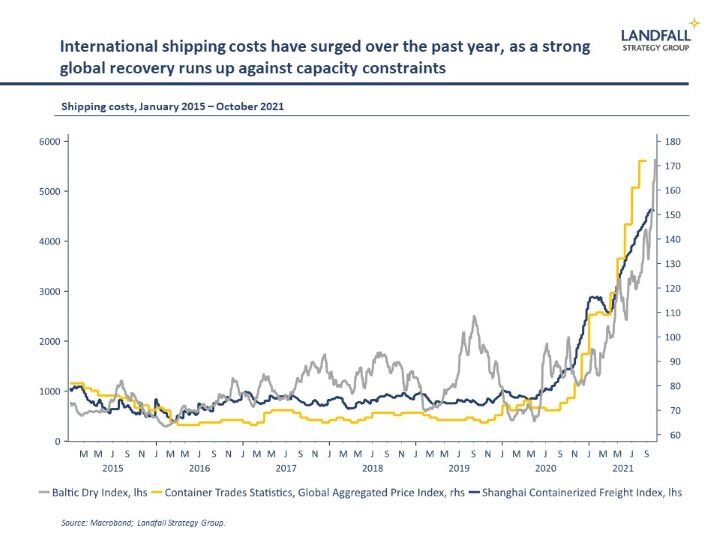

As it turned out, this was only the start of a much wider set of disruptions. The rapid global economic rebound, combined with constraints on the global shipping network, has created pressures across the system – with multi-month delays in shipping goods across the world as well as substantial increases in shipping costs.

From stuck ships to debt defaults

In a linguistic quirk, the world’s attention has shifted from the global economic impact of the Ever Given to Evergrande, China’s largest property developer. Indeed, Evergrande is likely to be a much more significant global economic event over time.

Evergrande has debts of over $300 billion, which it is now unable to service in full. It has become one of China’s largest and most important companies through aggressive, debt-fuelled expansion (China’s growth model in microcosm). But policy changes and economic fundamentals have created a perfect storm.

The direct costs of Evergrande are likely to be managed, imposed on holders of Evergrande’s equity and debt (its shares are down by 85% over the past year). And companies and economies that are exposed to the construction sector in China have also suffered losses. Iron ore prices are down by ~40% since July, and partly in response Hong Kong equities have sold off heavily.

However, China’s scale and political model gives it an ability to absorb this debt and reallocate it across the system – we are seeing this already, with parts of Evergrande in the process of being sold off. China has a playbook for dealing with these things: there will likely be no bail out for investors (note the new emphasis on ‘common prosperity’) but household exposure to Evergrande will be managed.

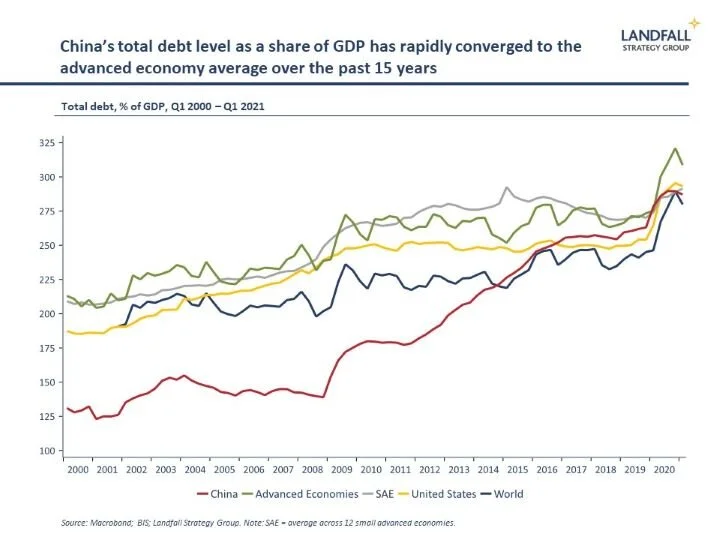

The broader impact is on China’s growth model. Debt-driven property investment has been a central part of the Chinese growth model over the past 20 years. But this model has run into constraints, with huge over-supply (perhaps enough for 90m people), an aging population, and so on. Ken Rogoff recently estimated that real estate accounts for 29% of China’s GDP, well ahead of other economies that have encountered real estate crises.

China’s overall debt level was ~290% of GDP in Q1 2021, in line with levels seen in advanced economies, having grown substantially from ~140% of GDP in 2008. This imposes limits on further debt-driven growth.

It is unlikely that the Evergrande situation will lead to a deep financial crisis in China, although the risks are higher than they were a decade ago. But it will take time to transition to a new growth model that emphasises consumption and productive investment; and this will require significant and sustained policy commitment. In the meantime, a weaker contribution from the real estate sector will lead to a deceleration in China’s growth.

China has become a less open economy as it has become larger, with an import share of 16% of GDP down from a peak of 28% of GDP. And the new dual circulation strategy will likely move it further in this direction, perhaps reinforced by its closed border policy to contain Covid.

Even so, a slowing Chinese economy will have spillover effects into the global economy through lower Chinese import demand; China accounts for ~11% of global imports of goods and services.

The strong Chinese economic recovery over the past 12 months has supported the global economic recovery. But this dynamic can work in reverse as well. Countries like Australia and New Zealand, where China accounts for 31% and 40% respectively of merchandise exports, are particularly exposed.

The Evergrande experience reminds that as China becomes a larger share of the global economy, it adds to the overall global risk profile. It is unusual for an emerging market, with the associated economic risk profile, to be one of the largest economies in the world.

A rolling series of global shocks

For all of the talk of globalisation weakening and decoupling, both the Ever Given and Evergrande events show that we remain exposed to a tightly networked global system. The dense linkages have made the global economy more efficient, but have also increased the risk profile. And the Covid pandemic is of course a powerful reminder of our global connectedness.

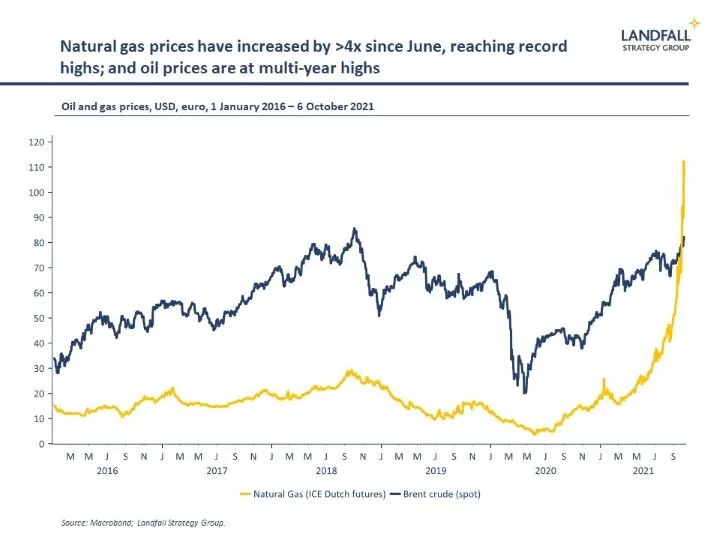

We should expect more of these risks as structural change works its way through a complex global system, from the energy transition to international economic rebalancing. This is reinforced by the strong global recovery from the Covid shutdown, which is putting real pressure on the supply side of the global economy. From semiconductor shortages to high energy prices and accompanying constraints on production, a rolling series of global shocks are being generated.

Some of these emerging pressures are temporary and will fade as the supply side responds. But structural responses are also required to respond to a high risk world, from a greater focus on ensuring resilience (e.g. supply chains) to managing concentration risk (e.g. strategic autonomy). And investment is required to strengthen the capability to manage these exposures, from renewable energy capacity to public health.

Each of these multiple shocks is specific and idiosyncratic, but together they speak to a global system under pressure. Prepare for more turbulence ahead.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

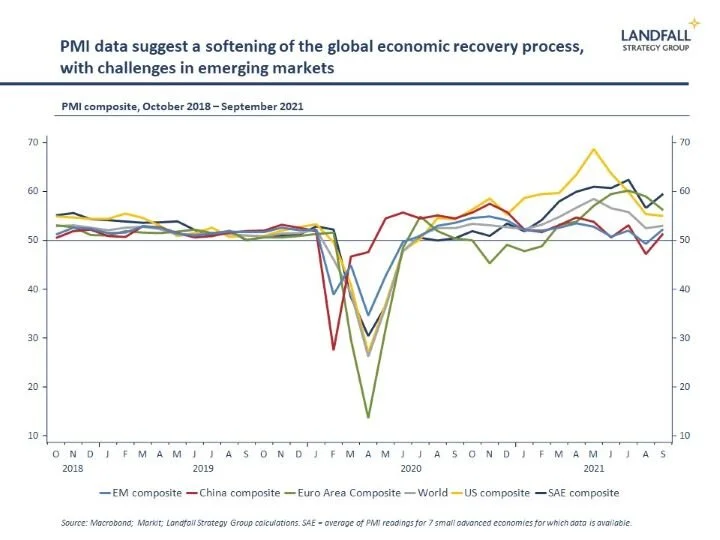

PMI data indicate that the strength of the global economic recovery process is fading, with September levels below their recent peaks. For most advanced economies, this is a second derivative issue: economic activity remains healthy, but is slowing. However, there are some more questions about the strength of the recovery in emerging markets – including China – that are more exposed to the direct effects of Covid-19, closed borders, and disruptions to supply chains.

Around the world in small economies

Covid has had a meaningful impact on populations. Singapore’s population shrank by 4.1% in the year to June 2021, in large measure due to fewer foreign workers. On the other hand, Finland enjoyed a baby boom that has pushed back the start of its forecast population decline.

Ireland tops Bloomberg’s Covid resilience index, followed by Spain, the Netherlands, Finland, and Denmark; New Zealand and Singapore drop sharply on their latest lockdown measures. In other Covid news, Israel vaccination passport now require a third shot: the evidence so far is that the third vaccine shot is very effective.

Singapore’s central bank continues to back crypto, as part of a drive to strengthen Singapore’s hub status. And New Zealand’s central bank is considering issuing a digital currency.

Tensions between Lithuania and China continue across a range of issues; and Lithuanian firms are now facing disruptions to Chin-based supply chains.

In green news, there is a cross-party agreement in Denmark for a binding limit to agricultural emissions by 2030. And Austria has announced plans to introduce a €30/tonne carbon levy (rising to €55 over 4 years) to control emissions – funding lower taxes and better access to public transport.

Several Nordic countries have implemented or announced higher tax rates, particularly on high income or high wealth taxpayers.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon argues that she has ‘time on my side’ in her efforts to move to a positive referendum result on Scottish independence. And time has been in plentiful supply in Dutch politics: over six months after the election, the end is finally in sight for the coalition negotiations – likely with the same coalition as before the election.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling