Global institutions are creaking

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

From Washington to Geneva and beyond, the past few weeks have provided more evidence that multilateral institutions are creaking under the pressure of a changing world. Big power rivalry is playing out in these institutions, weakening their effectiveness, at the same time as structural changes in the global economy demand policy innovation – from climate change to global trade.

The IMF and World Bank have been caught up in scandal about the current IMF MD’s (and former World Bank Group Chief Executive) involvement in shaping China’s ranking in the now discontinued Doing Business rankings. This leaves a stain on the reputation of those involved – and their respective institutions.

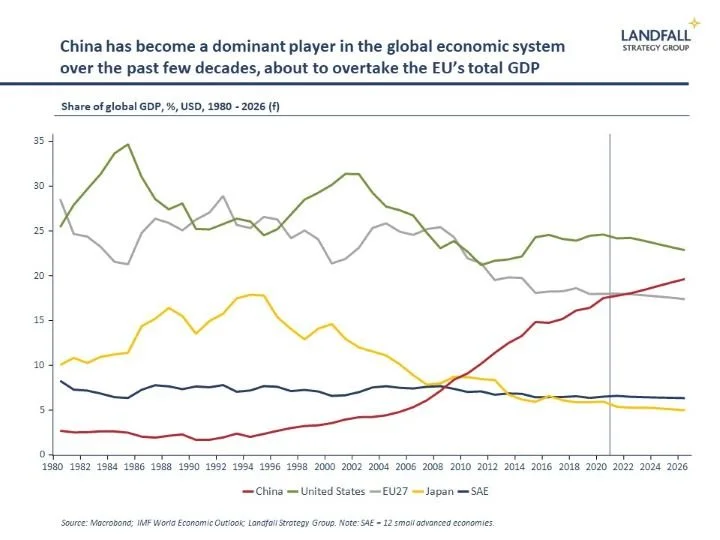

But it also speaks to geopolitical tensions and changing power structures. The US objected to actions that favoured China, and were apparently inclined to let Dr Georgieva go; whereas the Europeans backed her. These big power tensions greatly complicate the task of running the Bretton Woods institutions: the US is the largest shareholder, but China is a central economic player.

And the role of the World Bank and the IMF is being overtaken by other institutions. The Fed is the world’s provider of global liquidity and operates swap lines with central banks around the world. Last week’s Fall meetings showed the high quality analysis from these institutions, but they are no longer dominant.

In Geneva, the WTO continues to struggle. The current DG is musing about resigning after less than 12 months in the job; the previous incumbent also left early. No meaningful global trade rounds have been delivered for over 25 years, with little/no progress on recent negotiations, and trade restrictions are mounting up.

These outcomes are partly due to the objections of member countries like India and South Africa. But geopolitics is also a significant factor. President Trump threatened to pull the US out of the WTO because of alleged preferential treatment of China; and successive US Administrations have refused to appoint Appellate judges. The US Trade Representative visited the WTO last week (the first official visit in several years) but offered little to revive the organisation.

It is also striking that multilateral institutions – from the WHO to the IMF – have not been central in the Covid response; national governments (and the EU) have been the dominant actors.

A changed world

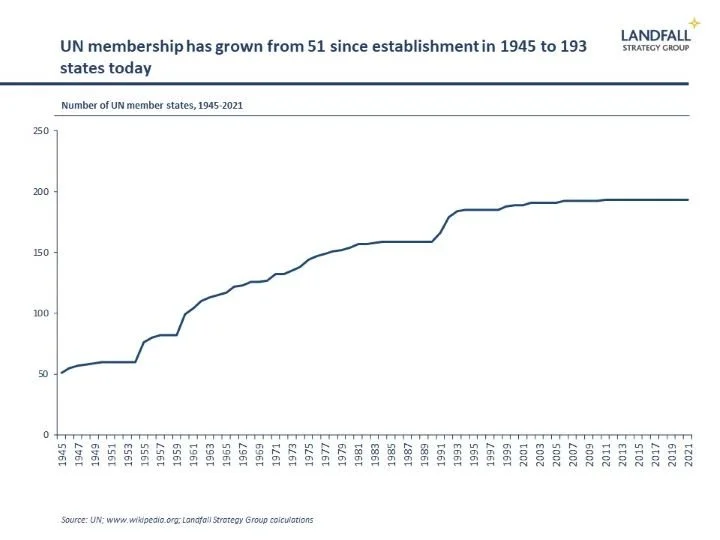

Post WWII institutions created to govern the international system were designed for a particular (US-led) environment in a less complex world. The growing strategic rivalry with China changes this context, creating deep challenges. It is hard for C20 institutions to confront C21 challenges in a C21 context.

US/China strategic rivalry also constrains new institutions such as the G20. After an effective G20 response to the global financial crisis, the G20 has not delivered much. Last week, President Xi did not dial into a G20 leaders’ meeting on Afghanistan and he is not attending the flagship meeting in Italy later this year. The G7 is a more coherent grouping at the moment.

The COP26 meetings in Glasgow are unfortunately unlikely to yield much progress in terms of new ambitious commitments, with leaders like Mr Xi and Mr Putin not attending. Even on existential issues, international cooperation is hard in the context of strategic rivalry and competing national interests.

These challenges are not new but recent events feel a bit like a tipping point in the effectiveness and legitimacy of international institutions. The similar tensions across a range of institutions suggests that structural dynamics are at work.

How did you go bankrupt?

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

This institutional weakness makes it more difficult to make progress on critical global issues. And it exposes smaller countries (reliant on an open, rules-based system) to big power politics.

Far-reaching reform to global institutions is often discussed, from a new Bretton Woods system to a reformed UN. But these often feel utopian: substantial strategic cooperation between the US and China is unlikely for some time, and the current key actors are unwilling to give up power. The more likely end state is institutional irrelevance rather than fundamental reform.

Institutional creative destruction

So there is a need for institutional creative destruction to develop institutions that can deliver in a changed global economic and political system. The good news is that there are examples of effective institutional approaches as countries look for new ways forward.

This is evident in trade architecture: regional or plurilateral agreements, and creative open platforms that can be expanded over time (e.g. CPTPP, RCEP, digital trade agreements in the Asia Pacific). These deals are frequently driven by small countries such as New Zealand and Singapore that are exposed to trade and investment barriers.

Interestingly, the OECD is perhaps the most effective post-WWII institution in the current environment. The OECD has a limited membership, strong analytic capability, and is an explicitly values driven organisation (openness, markets, democracy). It has the flexibility to make progress, and can provide open platforms.

The OECD has just provided the platform for a global corporate tax agreement (136 countries have signed on); and the OECD SG has proposed a similar model to agree a common approach to carbon pricing.

In the security space, smaller coalitions like the Quad and AUKUS are emerging that are based around shared values and interests around more narrowly defined goals.

And it is national governments (and coalitions of governments) and firms that will lead in reducing emissions. The EU is aggressively positioning itself as a green leader, and there is increasing firm and investor commitment to low emissions activities.

These more flexible, focused approaches, organised around open coalitions of the willing, are more likely to work given current realities than ‘one size fits all’ global institutions. Investments should be made in innovative institutional approaches to advance an open, rules-based system - perhaps the EU joining the CPTPP?

A portfolio approach to international cooperation may be messier than a fully multilateral approach, but it reduces the risk of inertia and may lead to more innovation.

Get in touch to let me know what you think about this note. And I am available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

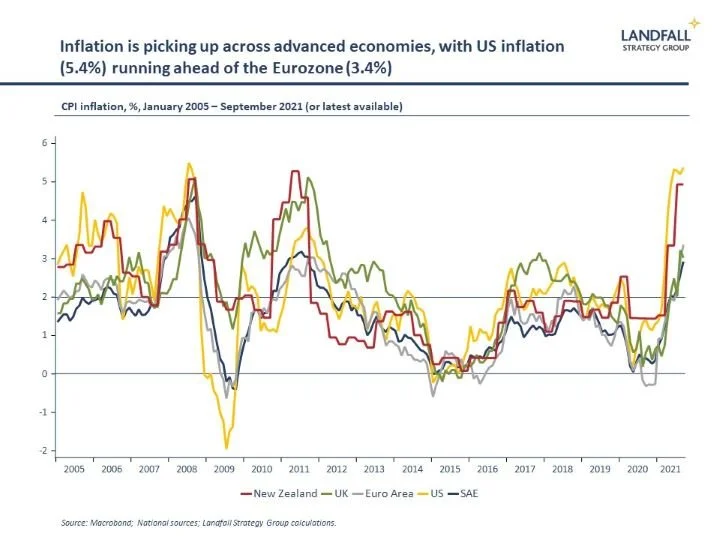

Concerns about higher inflation continue. US inflation came in at 5.4% in September, the highest since 2008. Inflation is also rising in the Eurozone (3.4%) and the UK (3.0%), but pressures are more acute in the US. Across small advanced economies, recovering strongly and deeply exposed to global dynamics, inflation is also rising – led by economies such as New Zealand. The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook, released last week, picks inflation to peak this year before declining to under 2% across major advanced economies by 2023.

Around the world in small economies

Ireland agreed to the OECD-brokered global corporate tax deal, having secured some concessions on the minimum tax rate wording. This is estimated to cost Ireland about €2 billion a year in reduced tax revenue. However, Ireland’s government budget – released last week – forecast a declining government debt share even as spending and investment grow.

The Dutch, famous in Europe for their hawkish fiscal stance, are discussing amending their domestic fiscal guidelines to allow for greater green investment (as part of coalition negotiations). This mirrors German coalition negotiations, and may have implications for the way in which the EU’s Stability & Growth Pact will be renegotiated.

Singapore’s advance estimate of Q3 GDP reported growth of 6.5% (0.8% on the quarter, following a quarterly contraction in Q2). Despite supply chain disruptions and Covid restrictions, full year growth is expected to be in the 6-7% range.

New Zealand’s Q3 inflation came in at 4.9% for the year (2.2% qoq), well above expectations, with strong contributions from housing as well as energy prices. The central banks of New Zealand and Norway are leading other advanced economy central banks in lifting policy rates, with more increases likely to come.

Singapore is moving to relax Covid restrictions, including a partial reopening of its borders – stealing a march on Hong Kong, which is following the aggressive approach of the mainland.

New Zealand has secured a FTA with the UK, almost 50 years on from New Zealand losing preferential market access to the UK - its largest export market at the time – when the UK joined the European Economic Community.

Chinese state-backed firm Cosco now own 67% of Piraeus Port in Greece, seen as part of China’s Belt & Road Initiative. However, concerns are growing - both in Europe in terms of Chinese control of strategic infrastructure in Europe, as well as in Greece in terms of whether Cosco is delivering the benefits it promised.

A study of over 1% of Iceland’s workforce found that a reduction of working time by 3-5 hours a week allowed (public sector) workers to get paid the same, while maintaining productivity and improving personal well-being. I regret to advise that I have not figured out how to make this work for me…

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling