Playing the inflation long game

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Inflation – and the inflation debate – is heating up. Recent inflation readings in the Eurozone, the US and the UK, as well as Australia and New Zealand, have come in above expectations.

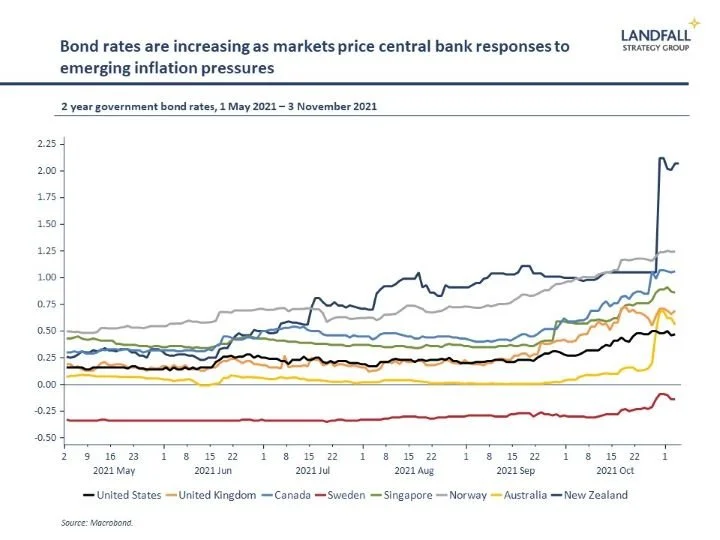

Opinions vary widely on how persistent these inflationary dynamics will be. Some central banks (Norway, New Zealand) have already lifted rates, and bond markets are pricing in rate rises by large economy central banks. But the ECB, the Fed, and the Bank of England remain unpersuaded.

Accelerating from 0 to 100

There are good arguments on both sides of the inflation debate. Resolving the issue is complicated by the unprecedented nature of the Covid shock and the speed of the recovery. The global economy is moving from a hard shutdown in 2020 to a very strong recovery process.

So it is not surprising that pressures and constraints are emerging across the global economy, from supply chains to energy prices and skills shortages. As well as inflation.

But recent data should not be over-interpreted as necessarily a resurgence of broad-based inflation. Inflation will be higher for longer than expected a few months ago, but these pressures may plausibly weaken significantly over the next 12 months.

For example, supply chain disruptions, as well as energy and commodity prices, may ease as bottlenecks are addressed and consumers rotate from buying goods to consuming services; China’s growth may slow markedly; and fiscal policy will become less stimulatory.

However, vigilance on inflation is required. This is particularly so given that many advanced economy governments are likely to continue to run high-pressure economies. Fiscal tightening is likely to be gradual so as not to endanger the recovery – and increased government capex is likely. And on monetary policy, my assessment is that there will be economic and political constraints on lifting interest rates.

Expanding the supply side

More importantly, policy vigilance on inflation will be required over a longer period as price pressures associated with structural changes in areas from labour markets to globalisation and climate change play out – reinforced by relatively expansionary macro policy. Policy instruments beyond monetary policy will be required to manage these medium-term inflationary pressures.

This matters for economic outcomes. But the politics of higher inflation are also challenging. Periods of high inflation often lead to political turbulence.

Economic policy should focus on expanding supply-side capacity, and raising productivity. This should be based on a coherent economic strategy. Simply asserting that higher wages and costs will deliver productivity without further policy action (as suggested by the UK’s Prime Minister) is not enough.

Consider a few examples where structural changes will require supply side responses to manage price pressures.

First, changes in the nature and location of jobs in the post-Covid economy are creating mismatches between labour supply and demand – leading to skills shortages and wage pressures emerging across the economy (compounded by constraints on migration). In addition to talk of the ‘great resignation’, technology and new business models are creating new jobs and displacing others quickly and at scale. These pressures will endure for some time.

These structural changes in labour markets, accelerated by Covid, could lead to wage and price inflation unless met with policies that enable better matching of labour demand and supply – and support labour productivity growth.

Investing in skills policy, active labour market policy, and in well-judged migration policy, will help alleviate pressures on labour markets. Done well, wages can grow strongly with productivity improvements offsetting any inflationary effects.

Similarly, investment in capital and technology can push out the supply side of the economy – and support the labour market transition. The rapid, at-scale adoption of technology during Covid – and the expectation of a global ‘investment bonanza’ – will contribute to stronger productivity growth over time and contain inflationary pressures.

Governments can support productivity-enhancing investments by firms, and make complementary investments in public infrastructure (from high speed broadband to funding research).

Second, the intensity of globalisation, which has been a deflationary force over the past few decades, is no longer increasing – and the deflationary impulse of large emerging markets like China is weakening/reversing. And there are costs with trade and investment frictions (e.g. US/China), as well as the pressure for localisation and strategic autonomy.

Governments (and firms) should retain a strong bias towards openness, and strengthen resilience in a disciplined manner to manage the risks of higher cost structures.

Third, there are cost pressures associated with the transition to net zero. Although renewable energy prices are reducing sharply, the pricing is not yet always competitive with fossil fuels; and the broader transition to a low emissions economy will involve costs (including carbon taxes). This can be seen as a negative supply side shock, which is likely to have an inflationary impact.

The transition to a low emissions economy will require substantial investments in new capacity. Over time, renewables should be consistently cheaper and productivity enhancing. But in the meantime, governments will need to manage the distribution of the costs of this transition across the population and over time – including funding new low emissions infrastructure, technology, and innovation.

Playing the long game

These structural dynamics across the global economy will shape inflation outcomes beyond the near-term economic reopening. The governments (and firms) that act to strengthen productivity and expand supply side capability are likely to manage inflation pressures relatively well. The policy response needs to extend well beyond monetary policy.

Small advanced economies, which have a bias towards supply side over demand side measures to generate productivity growth, are worth watching in this environment. From Singapore to the Nordics, several have been developing relevant supply-side measures as part of their post-Covid economic strategies.

Many advanced economy governments have used macro policy effectively to exit the Covid crisis. But a new policy emphasis is now required: structural changes require a supply side response. Without this, expect higher trend inflation, weaker economic outcomes, and greater economic and political turbulence.

Get in touch to let me know what you think about this note. And I am available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

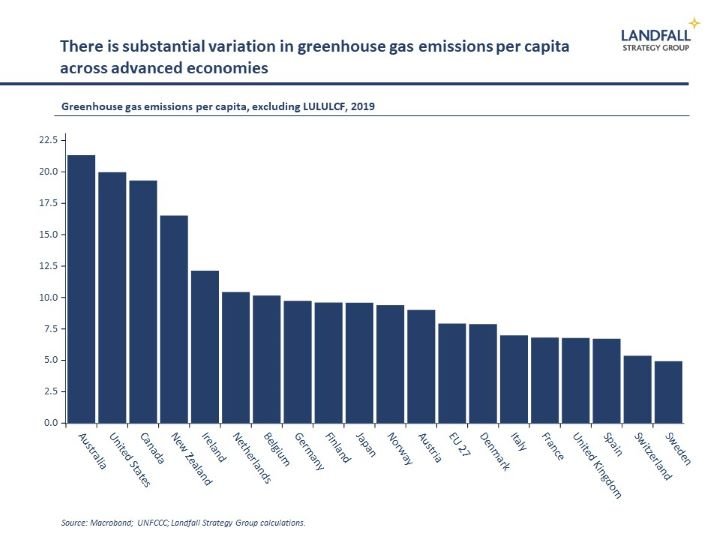

As the COP26 meetings launch in Glasgow this week, it is striking how much variation in emissions per capita there is across advanced economies. This variation in emissions intensity goes some way to explaining variation in the ambition of national targets: Australia and the US have the worst records, whereas many European countries perform relatively well. The encouraging news is that emissions per capita has been consistently reducing across advanced economies – although not by enough.

Other writing

I wrote a guest blog post (with multiple charts!) for Macrobond Financial on the general resilience of globalisation through Covid. The piece is available here.

Around the world in small economies

Strong Q3 GDP data has been reported for several small economies: quarterly GDP readings were strong in Austria (3.3%), Belgium (1.8%), Sweden (1.8%), and Singapore (0.8%).

Adrian Orr, Governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, argued that ‘climate change could lead to a prolonged period of faster inflation that requires a monetary policy response’. The Reserve Bank released a paper on how it would mitigate and manage the significant economic risks associated with climate change.

The Sweden/China relationship has been challenged over the past several years, but Chinese-owned Volvo launched its IPO last week. Volvo is transitioning to an all-electric line-up, and the IPO was well-received after governance changes were made.

After a visit to Israel, the FT’s Gideon Rachman noted the ‘mood of buoyant optimism among the country’s political and business leaders’ as growth continues (Israel now has a higher per capita income than the UK), VC money pours in, and economic engagement in the region takes off.

Singapore is rewriting the rules for global cities, including a rebalancing between foreign and local firms and workers.

The UAE is facing growing economic competition from Saudi Arabia, its large economic neighbour. Saudi Arabia is aggressively attracting foreign companies and talent to locate in Riyadh rather than Dubai.

Greece is embarking on a major energy transition. ‘As wealthier European countries like Norway and Denmark make strides re-engineering their economies to be more climate friendly, Greece offers a test case of whether - and how effectively - Europe’s poorer states can turn away from fossil fuels while providing buffers for those threatened by the change’.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling