Climate change politics is local

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

We all know what to do, we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it’, Jean-Claude Juncker.

Progress was made at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow. Although the commitments made fall short of what is required, it was more than ‘blah, blah, blah’.

But addressing climate change is a deeply political process, and policy approaches need to respond to domestic political realities to make meaningful progress. In thinking about the best way forward, it is useful to learn from the good and the bad of managing globalisation.

First, avoid utopianism. The claims that free trade would inevitably create prosperity and that the distributive impacts would be taken care of by rising incomes (and assumed compensating policies) led to policy neglect. Now similar claims are made that aggressive climate change policy will simultaneously deliver net zero as well as green jobs and prosperity. From the US to the EU and beyond, the green transition is portrayed as central to strong and inclusive growth.

I’m in favour of both trade liberalisation and net zero, but the associated costs and risks need to be recognised and managed. A utopian view that sees everything as win-win is likely to lead to political pressures that undercut the feasibility and sustainability of effective policy. And there is no time for delay in reducing emissions.

International economic integration has led to a backlash in some countries. For example, the ‘China shock’ on US manufacturing, and the politics around migration in the UK, contributed to the election of Mr Trump and the Brexit vote respectively – both of which led to reversals in integration.

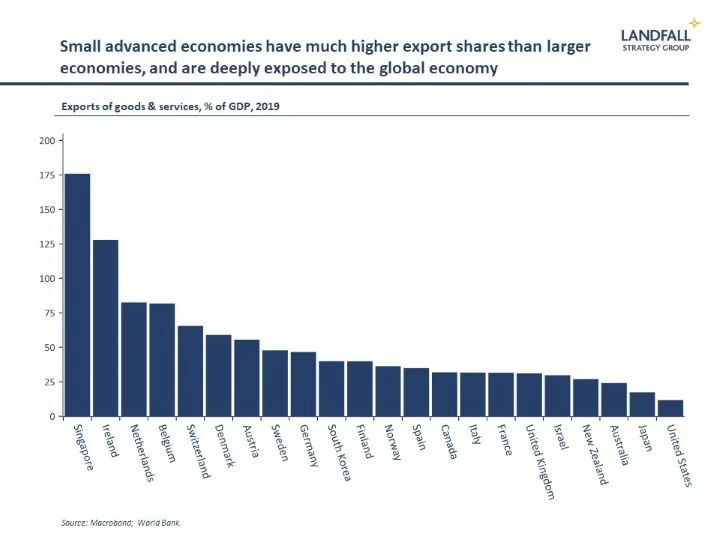

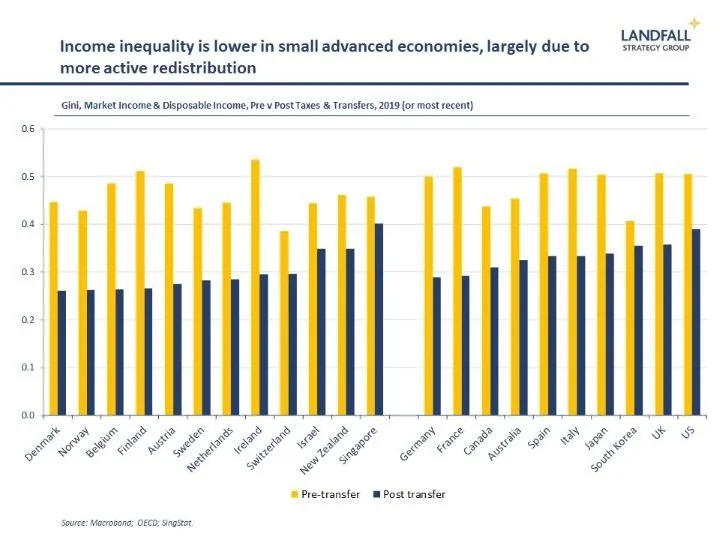

Second, deliberate policy responses can capture the opportunities and manage the risks. It is striking that political pushback on globalisation has been stronger in the US and the UK than in small open economies that have managed their deep exposures to the global economy.

Small advanced economies have focused on managing risks and ensuring that the costs and benefits of global engagement are broadly distributed; through social insurance, active labour market policy, and so on. And they have actively worked to develop competitive advantage in global markets. This policy approach has allowed small economies to maintain high levels of support for open policies.

From globalisation to climate change

This experience is relevant to designing climate change policy. As with globalisation, the net zero transition offers the potential for substantial economic benefits: new jobs in the green energy sector, new low emissions growth sectors, and cheaper energy sources over time (as well as avoiding the economic costs of environmental disaster).

Indeed, some emissions reducing activities come at negative cost with existing technology - and some companies already see a market for low emissions goods and services.

But there are also significant economy-wide transition costs: emissions intensive goods and services will become more expensive (energy and transport); the value of substantial amounts of capital will be destroyed; and there will be disruption to labour markets. It is a significant negative supply side shock. And people on lower incomes will often be disproportionately exposed to these costs.

Public concerns about risks to household incomes are slowing policy change: note the protests in response to rising energy prices or proposed carbon taxes, from France to New Zealand. The climate-conscious Biden Administration has responded to high energy prices by exhorting OPEC to increase supply.

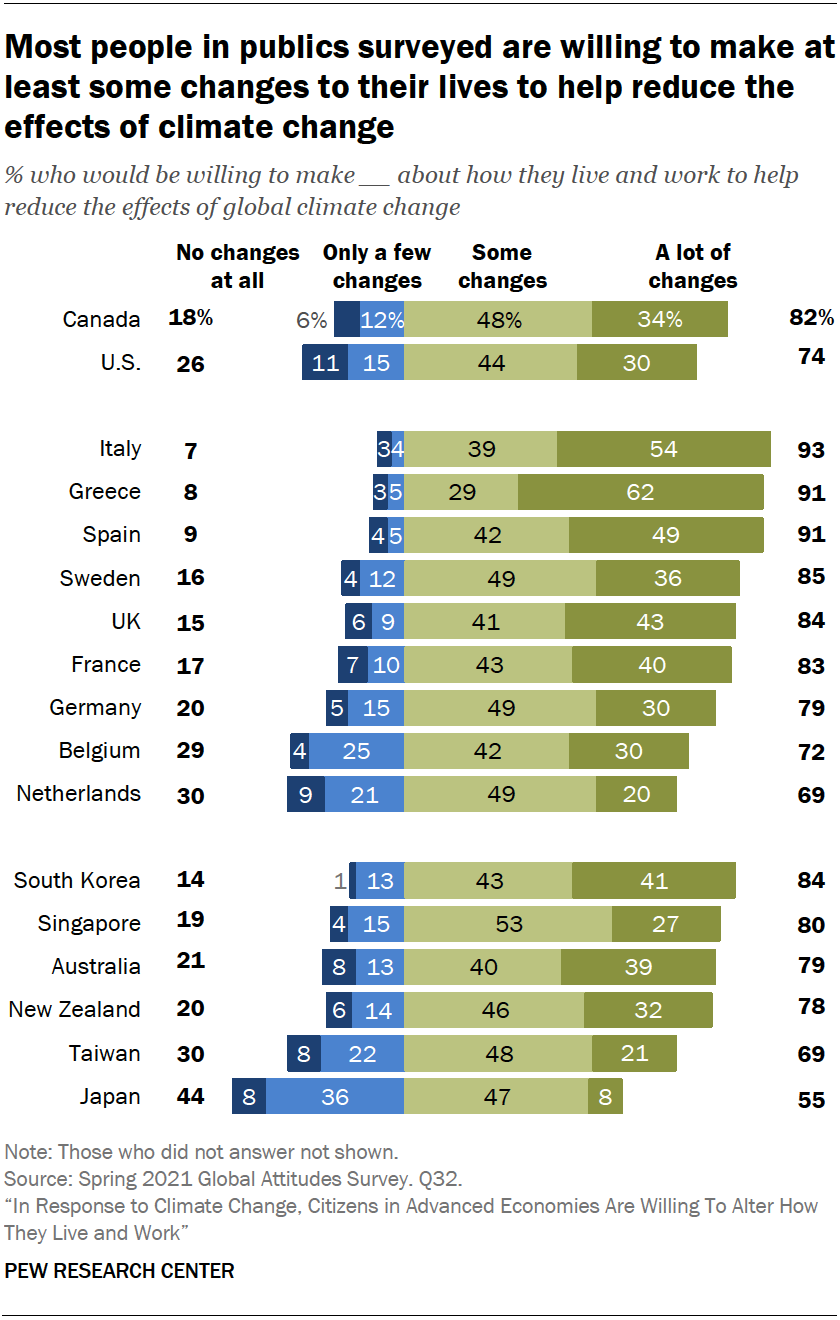

Although surveys report widespread public concern about climate change and support for policy action, there are limits to the public’s current appetite for substantial change.

These political realities explain why aspirational statements of political intent and net zero targets are running well ahead of policy action. In politics, losses are weighted more heavily than gains.

The international politics of climate change also complicate the transition. The costs and benefits are unequally distributed around the world. Whereas many developing countries pushed trade liberalisation, many fear the economic and financial costs associated with a rapid transition to net zero. The financial support required to create political space in developing countries has not yet been forthcoming.

So what to do?

The insight from small economies that have managed globalisation best is that getting the domestic politics right is the precursor for meaningful progress. Climate change policy needs to be oriented around widely-shared welfare.

Without a well-developed, ambitious policy strategy to maximise opportunities and manage the costs and risks of the green transition, there will not be broad-based political support for ambitious climate change action – and there will be a likelihood of policy reversals.

This matters because a major economic transformation is required in a compressed time frame. The IPCC estimate that emissions will need to be halved by 2030 to hit the 1.5 degree target, on the way to net zero emissions by 2050. Updates prepared for the COP26 meetings show that there is a long way to go.

Actions to create the political space for this transformation include active labour market policy to provide displaced workers with skills and opportunities to move to new jobs; adapting national economic strategies to support opportunities in the low emissions economy, and reducing reliance on high emissions strengths; and providing compensation to those exposed to higher prices, such as through recycling carbon tax revenues.

Government balance sheets should also be used to support the transition – investing in renewable energy, supporting the development of new low emissions industrial and transport systems, and so on. This investment can help push the supply side out, encouraging the development of new technologies as well as supporting a fairer transition. The policy response has to be broader than simply implementing carbon pricing.

A rapid transition is more likely to be politically feasible if households and firms can see attractive alternatives, from compelling jobs and high quality public transport to competitive energy alternatives. At the moment, some low emissions policies (e.g. subsidising electric cars) are seen as supporting the preferences of the wealthy at the expense of the lower income.

Although international action on climate change is important and necessary, the binding constraint on progress is what national governments are politically prepared and able to do. Climate change politics remain largely local, and aggressive domestic policy innovation is needed to respond to these realities.

Get in touch to let me know what you think about this note. And I am available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

Switzerland, Singapore, the Netherlands, and Denmark top the 2021 edition of Landfall Strategy Group’s Economic Strength Index. I construct the Economic Strength Index on the basis of the specific factors that drive economic performance across small economies. Performance on skills & innovation, internationalisation, and institutional strength are particularly important. There is a tight relationship between the Economic Strength Index and variation in per capita income.

Around the world in small economies

Singapore Minister Chan Chun Sing delivered a lecture on Singapore amid great power rivalry, emphasising the need for ‘geostrategic entrepreneurship’ by small states.

Denmark’s strong outcomes through Covid can be attributed to strong social and political institutions, including trust in government and social norms. And Denmark reported strong Q3 GDP (+2.0% qoq), with GDP levels now up 4% relative to Q4 2019. Meanwhile, Sweden no longer stands out in terms of Covid management.

Restrictions are being tightened on unvaccinated people in order to control the spread of Covid. Austria is imposing tough fines on unvaccinated people that enter public spaces. And Singapore will soon implement measures so that unvaccinated people are responsible for the costs of their Covid-related medical care.

New Zealand finished its virtual hosting of the APEC meetings last week with the Leaders’ Meeting. In the final statement, measures to address vaccine nationalism, fossil fuel subsidies, and to reduce cross-border red tape were mentioned. Vangelis Vitalis, New Zealand’s senior official, provided this useful summary of outcomes.

Royal Dutch no more. Shell has followed Unilever in moving its headquarters and tax residence from the Netherlands to London, ending its dual-share structure.

Estonia has been a beneficiary of Brexit, attracting firms and people to its streamlined business environment.

And lastly, Iceland takes on Facebook’s Metaverse in this great video; an immersive experience without the ‘silly VR headsets’.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling