Geopolitics: follow the money?

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The past couple of weeks have seen contrasting approaches to managing commercial relations with China. JPMorgan boss Jamie Dimon offered an apology for suggesting that the CCP may not outlast his firm; whereas the WTA responded forcefully to the apparent detention of Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai, now suspending its tournaments in China.

These different responses are partly shaped by different economic incentives. Risks to JPMorgan’s expansion into the Chinese market would be strongly negative for shareholder value; while the WTA’s values-based stance is supported by a likely more limited near-term financial impact due to Covid cancellations - although even so, it has acted more aggressively than other similarly-positioned sporting franchises.

Economic incentives also provide insight into geopolitical dynamics. Unlike the Cold War, the big powers are deeply integrated into the global economy in terms of trade, investment, and technology. Increasingly the economic and political dimensions of bilateral relations interact with each other.

For example, China has a record of squeezing smaller economies to pressure them to alter their political behaviour – from Lithuania and Norway to Taiwan and Australia – in ways that impose economic pain without injuring itself. President Xi’s claim last week to an ASEAN meeting that China does not ‘bully smaller economies’ should not be taken at face value.

Geopolitics = f(economics) + …

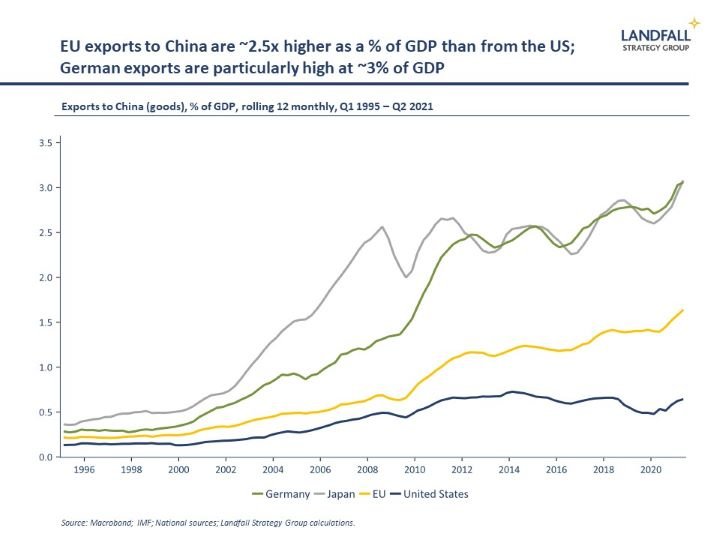

Variation in economic exposures to China provides a perspective on the more hawkish approach of the US to China than the EU (notably Germany). EU exports to China are much higher than from the US (both in $ terms, and as a % of GDP), and the EU’s overall trade relationship with China (exports plus imports) is now the biggest in the world.

More broadly, the EU is a highly open economy. The EU’s (ex-EU27) exports represent 22% of its GDP, compared to an 11% exports/GDP share in the US. The EU’s more externally-oriented growth model - and the number of jobs in these externally-facing firms - creates incentives to prioritise relations with key markets like China to a greater extent than in the US.

Under Chancellor Merkel, priority was given to German commercial interests. Led by France and Germany, for example, the EU agreed a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) deal with China in December 2020, even as the US was imposing economic sanctions on China. This deal was eventually suspended by the European Parliament after China imposed far-reaching sanctions on Europe (as well as due to pressure from other EU members).

‘It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it’, Upton Sinclair

In contrast, the US has been more prepared to disrupt its economic relationship with China through tariffs, investment sanctions, and so on. The external economy matters less to the US. Being hawkish on China is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement in Washington.

Even so, US exports and imports to/from China are now at record levels, suggesting limits to how far even the US has been prepared to go.

For its part, China is less reliant on external demand than 10-15 years ago (exports are 19% of GDP), and is pushing for greater economic self-reliance (‘dual circulation’). But FDI flows into China as a share of GDP now rival those into the US: it is still regarded as an attractive investment location.

Of course, as also seen in the WTA’s actions, economic incentives are not the only thing that shape international relations: values and broader strategic interests also matter.

Australia, for example, has taken a tough approach to China despite 40% of its merchandise trade exports being sold into China. Some Australian exports have been subjected to Chinese sanctions as a consequence; although strong Chinese demand for iron ore means that overall Australian exports to China have continued to grow.

The return of politics

There are some indications that short-term economic considerations are becoming less decisive. The US, the EU, and European countries (notably Germany), are increasingly focused on broader strategic considerations even at some economic cost.

The new German coalition agreement indicates a tougher stance is likely on China (and Russia), less influenced by commercial considerations. It talks of ‘system rivalry’ with China, references Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang, and is opposed to CAI ratification. This reflects a recalibration of German foreign policy, that even Dr Merkel now admits may have been a bit ‘naïve’.

Elsewhere in Europe, several other economies are adopting tougher stances on FDI screening, technology transfer, and so on – motivated by concerns about China. The EU released the first annual FDI screening report last week.

In the US, the annual US-China Economic and Security Review Commission report was released to Congress in November. It recommended a range of tough restrictions on US/China financial investment, as well as greater screening of supply chains and investments. This is not an official policy statement, but the recommendations of this body are taken seriously.

The focus of US action is moving from commodities towards high value, high growth areas of the US economy – from technology to finance – and runs counter to the preferences of at least some US firms in these sectors.

These moves are supported by changing public opinion in many Western economies. Recent surveys reveal deteriorating sentiment towards China in many advanced economies, and a preference for developing economic relations with the US rather than China (Singapore is an exception, along with New Zealand to an extent).

Active debates are underway in many advanced economies on striking a different balance between economic and broader political considerations in response to growing big power rivalry. Increasing fragmentation of the global economy is likely over time, with growing trade and investment flows within like-minded blocs. But ‘decoupling’ from China will likely be gradual because of strong economic incentives.

Globalisation will continue in a modified form (the subject of a future note), but the increasingly zero sum logic of geopolitics is a long way from the triumphalist globalisation sentiment of the 1990s.

I deliver presentations and engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

Chart of the week

Q3 GDP data showed a continuing global economic recovery across advanced economies (and China), although with varying intensity. Several economies in the Asia Pacific - from China and Taiwan to South Korea and Australia - have higher GDP in the year to Q3 2021 than in the year to Q4 2019 - as does the US. Many of the smaller European economies - from the Nordics to the Netherlands and Switzerland - also perform well, with GDP above or close to pre-Covid levels. Several of the larger European economies - along with Japan - are lagging, with GDP well below Q4 2019.

If you would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking here.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling