China & the ending of an era

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

After several decades of integration and opening up, recent developments suggest we may have reached the high water mark of China’s engagement with the global economy.

As examples from the past week or so: Didi announced its delisting from the New York Stock Exchange after its June IPO, with expectations of more Chinese delistings to come; China deleted Lithuania from its customs system (effectively banning its exports), and is organising a corporate boycott of Lithuanian firms; and China is preparing new restrictions on foreign investment in Chinese technology firms.

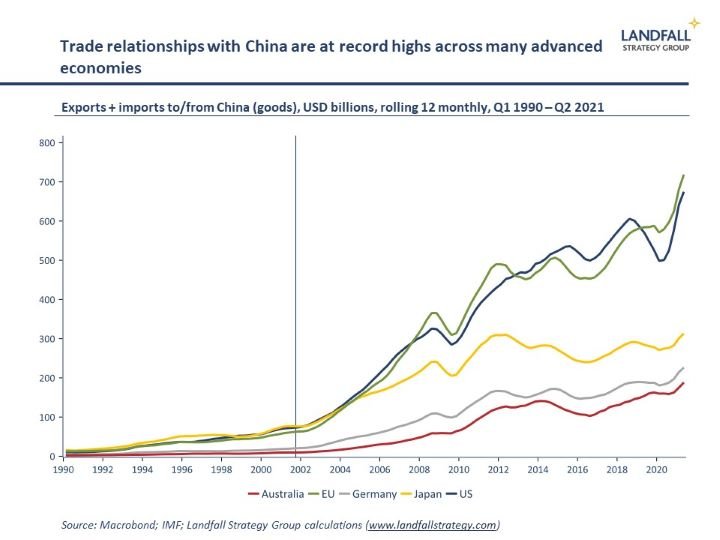

Until recently, economic tensions with China have been more of a shadow war. Despite the noise of trade wars, trade and capital trade flows between the West and China have continued to grow to record highs.

But political choices, both domestic and international, are now shaping economic behaviours to a much greater extent. China has an increasingly domestic focus; and the US, the EU, and others are taking a tougher stance on engagement with China.

Things aren’t like they used to be

These indications of a turning point in the nature of China’s integration into the global economy are particularly striking because they come on various significant anniversaries of China’s opening up.

50 years ago in 1971, President Nixon made a shock announcement of a trip to Beijing (undertaken in February 1972), which he subsequently termed ‘the week that changed the world’. As well as changing the shape of the Cold War, the breakthrough meetings between Nixon and Chinese leadership created a supportive environment for China’s subsequent reform and opening up. But Xi Jingping represents a clear break with the policies initiated by Deng Xiaoping.

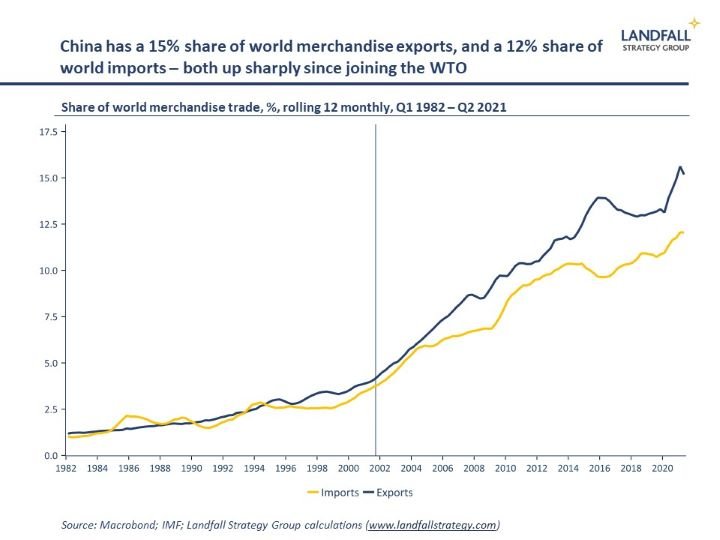

And 20 years ago tomorrow (11 December 2001), China acceded to the WTO. WTO membership formalised China’s entry into the global economy, and accelerated China’s integration process.

Since 2001, China’s share of world goods exports has increased from 4% to 15%. And it has become the largest export market for many countries. China has been central to the process of intense globalisation, becoming the factory of the world: exporting deflation, competition, and labour market disruption around the world.

But China is moving away from an export-oriented growth model. Part of this transition is inevitable as China has developed and because of its very large domestic market. Further declines in its export and import shares of GDP are likely. But this transition has been reinforced by recent political choices to strengthen self-reliance and reduce external exposures.

And under President Xi, China has adopted a more confrontational international political stance with a more inward-looking focus. China’s tough approach to Hong Kong provides an example of the heavier weighting on domestic political factors than on the costs of reduced global engagement.

There are also multiple recent examples of China squeezing smaller economies with which it has political disputes by weaponising trade flows, from Norway and Australia to Lithuania, in ways that are not WTO-compliant.

One marker of China’s changed positioning is the difference in international perceptions of China between its hosting of the acclaimed 2008 Olympic Games – in a sense, China’s global coming out party and perhaps the high point of Western hopes for engagement – and its hosting of the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics, now accompanied by diplomatic boycotts from the US and several others.

The start of (some) decoupling

China’s changing economic and political model, combined with geopolitical rivalry, will lead to some unwinding of economic engagement between China and Western economies (and beyond).

This will be deeply consequential for the global economy: China is the second largest economy in the world, the single largest exporter, a major FDI destination, and has 135 Fortune 500 firms (more than the US).

But although there will be some decoupling, this will be a gradual, bumpy, and costly process. The powerful economic incentives that have driven engagement between China and advanced economies have not disappeared, and these will shape the speed and nature of the decoupling process. Decoupling is a matter of degree, not a binary proposition.

Trade flows to/from China were at record-highs through Covid, partly on a rotation of consumer demand towards goods (see the ‘Chart of the week’ below). Chinese exports and imports were up 32% and 22% respectively in the year to November. This suggests that meaningful trade decoupling with China will take time.

However, the direction of travel is for reduced economic engagement between advanced economies and China. Some supply chains are moving out of China due to higher unit labour costs, even if this is a gradual process. Bilateral trade in sensitive products (such as advanced technologies) will likely reduce more rapidly in response to strategic autonomy concerns on both sides.

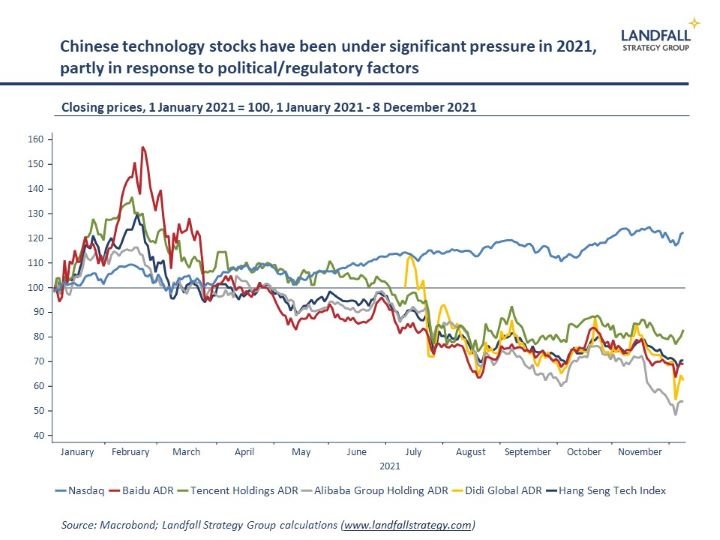

And although overall trade decoupling will be gradual, more rapid decoupling is likely in terms of investment flows. Listings of Chinese firms in the US are likely to reduce, due to Chinese pressure as well as enforcement of US regulatory requirements. China has just announced restrictions on foreign investment into technology firms, with similar measures already having been taken in the US. These developments have been negative for the pricing of Chinese technology stocks.

Tougher FDI screening regimes have been implemented in the US, across the EU, and elsewhere, in response to concerns about Chinese investment into technology and other strategic sectors.

As a consequence, there is likely to be fragmentation in the technology space between China and Western economies. Indeed, China is looking to shape technical standards and to strengthen relationships with non-Western countries in order to support the performance of its technology firms (on China’s terms).

Investment into non-sensitive sectors is less impacted, but still more challenging. China is imposing conditions on knowledge transfers, corporate behaviour, and public statements by firms, which will make it increasingly difficult for Western firms to meet consumer, investor, and government preferences in both China and in their home markets.

And the heightened domestic political risk around investing in China in previously non-sensitive sectors (education, ride-sharing) may create concerns about how investable parts of the Chinese economy are. So far, portfolio investment into China remain robust – but there are growing questions about the sustainability of these investment flows.

Although China will remain a key node of the global economy, the intensity of its connections with advanced economies will likely weaken. These dynamics will reshape global economic behaviour and performance: weaker import demand from China, reduced deflationary forces, constrained investment opportunities.

After the transformational impact of China’s rapid integration into the global economy over the past few decades, advanced economies should prepare for more disruption as aspects of this unwind over the next decade and beyond.

I deliver presentations and engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

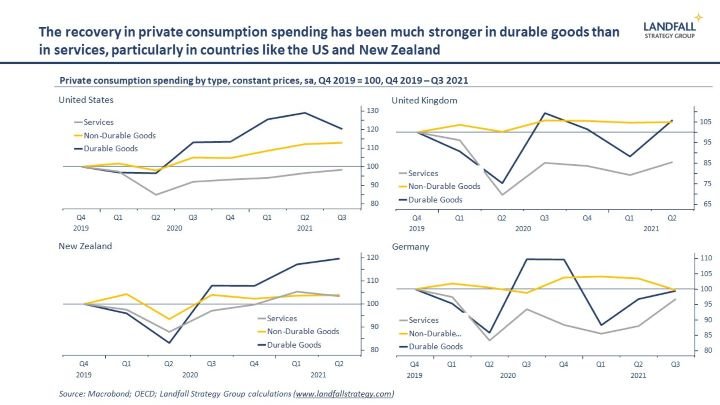

Chart of the week

Covid lockdowns have supported a sharp rotation of consumer demand away from services towards goods, particularly durable goods. People can’t travel or eat out, but they can buy electronics and furniture. This behaviour is seen across advanced economies, such as the US, the UK, and New Zealand; it is slightly more muted in some European countries. This demand for goods has supported world trade growth, but has led to global supply chain constraints as well as inflationary pressures. As Covid restrictions relax, some of these consumer behaviours - and the associated pressures across the global economy - should normalise.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling