Inflation, politics, & the post-Covid economy

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

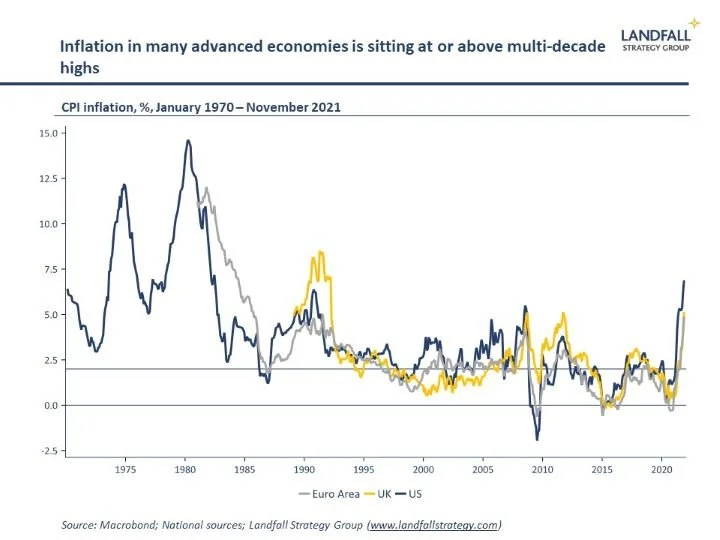

It has been central bank week, with announcements from the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England, and others (Norway, Switzerland). In response to inflation that has risen sharply to levels not seen for decades, many central banks have begun to tighten monetary policy – or to signal that they will do so.

Uncertainty remains about how persistent these inflationary pressures will be; it is plausible that inflation will moderate markedly through 2022 as frictions and constraints associated with the re-opening of the global economy ease. But central banks are under growing pressure to act.

Inflation is not popular

Indeed, inflation is more than an issue of economic management – it is also deeply political. First, the monetary policy regime is a political choice. Over the past few decades, central banks across advanced economies and beyond were given independent mandates to target price stability. But this political consensus has begun to shift, with central banks being encouraged to weight real economy outcomes more heavily.

And second, inflation is deeply political because it turns out to be unpopular. In the US, some Congressional Democrats (as well as Republicans) are currently pressing the Fed to raise rates to respond to rising inflation. US consumer sentiment is weakening despite healthy employment outcomes, plausibly on concerns about rising prices.

And public concerns about rising prices are seen from the UK to New Zealand and beyond. In more extreme cases, very high inflation is associated with political and social instability. Turkey’s inflation rate of ~20% (due to policy mismanagement) is posing a significant political risk to President Erdogan.

One reason for the unpopularity of inflation is its distributive consequences. Inflation is often regressive because people on lower incomes spend more of their income on non-discretionary consumption. Indeed, food and energy prices are currently rising sharply as well as home rental prices.

Beyond this, the current spike in inflation is having some specific redistributive consequences that are shaping the post-Covid global economy.

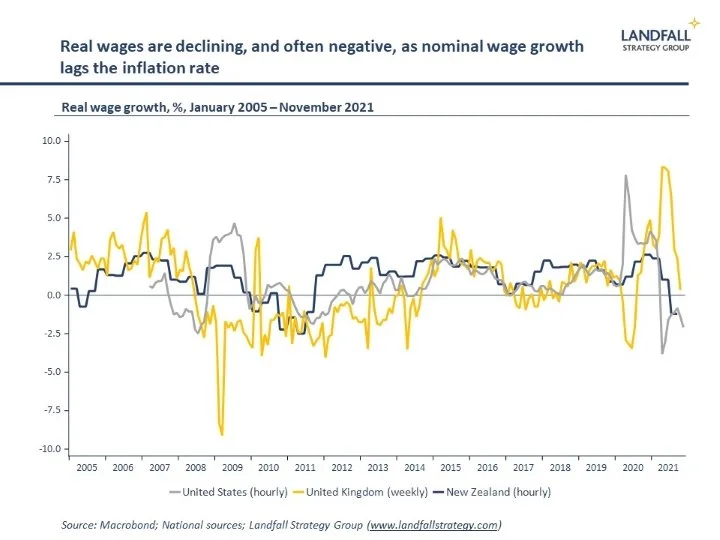

Reducing labour income shares

First, the rapid rise in inflation has led to negative real wage growth in many advanced economies as wage growth has been out-paced by inflation. Although labour markets seem tight (low unemployment, high quits rates, high reported labour shortages), this has not translated into real wage growth. Real wage growth is lagging labour productivity growth in many advanced economies.

This may be a timing issue: wage growth may strengthen due to tight labour markets over the coming period. And if inflation turns out to be temporary, then real wage growth may increase. But these outcomes may also reflect structural features like the weak institutional bargaining power for labour, which constrains the pace of wage growth.

Either way, negative real wage growth amplifies the reduced purchasing power of households due to inflation – a key reason for the unpopularity of higher inflation.

Inflation is placing further downward pressure on the labour share of national income, as many firms have been able to pass on higher input costs - with profit margins expanding. Perhaps unsurprisingly, business confidence is markedly higher than (declining) consumer confidence across advanced economies.

And in many economies, these concerns are compounded by rapid house price inflation during Covid – and consequent increases in rental prices. Strong house price appreciation has damaged housing affordability, with strong increases in house price to household income ratios (to record levels in many countries).

Financial repression

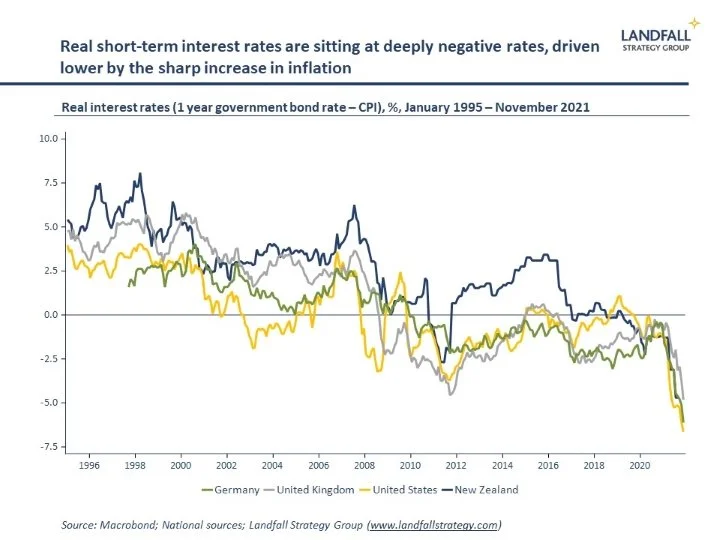

The second distributive impact of inflation is on borrowers. I will focus on government borrowing. Real interest rates have become more negative over the past several months as inflation has increased. These reduced borrowing costs provide additional fiscal space for governments, although eroding the return to holders of government bonds.

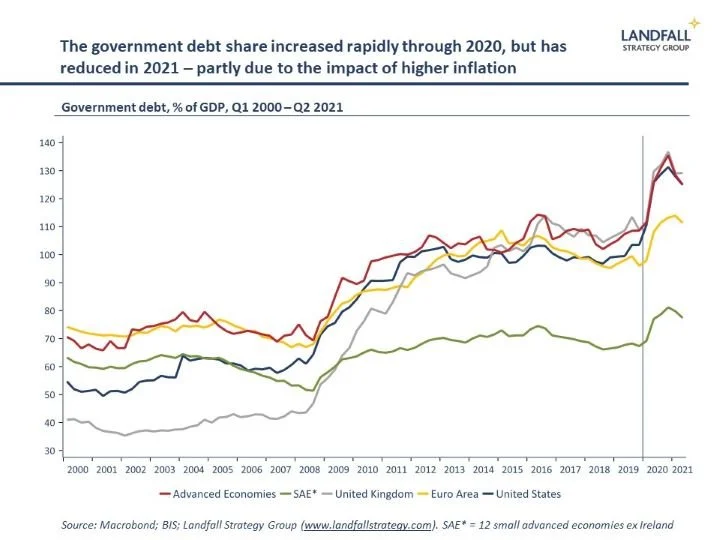

Improvements in the fiscal position can be delivered in a few ways (short of defaulting): through strong GDP growth; fiscal tightening; or financial repression, where people are forced to hold bonds with negative real interest rates. The latter approach was seen in some economies (eg the US) in the post WWII period, which – combined with strong GDP growth rates – contributed to rapid reductions in government debt levels.

Another way of making this point is that when the nominal GDP growth rate is higher than the borrowing cost, downward pressure will be applied to the public debt stock as a share of GDP. To calibrate, nominal GDP growth in 2022 is forecast to be ~9% in the US, ~8% in the UK, and ~6% in New Zealand – well above government borrowing costs.

So although large fiscal deficits have been run during Covid, the impact on government debt has been controlled by strong nominal GDP growth (to which inflation has been a major contributor). Indeed, government debt/GDP (as well as private sector debt/GDP) has been reducing through 2021 despite ongoing fiscal deficits.

Inflation is providing more fiscal space to governments, reducing the need for reductions in spending (or revenue increases) to reduce debt levels – which would also likely have regressive distributional consequences. To some extent, this dynamic offsets the other regressive effects of inflation.

Looking forward

Although financial repression is not yet a deliberate strategy, these outcomes are consistent with a move over time to a new macro policy regime – where fiscal policy is the primary policy instrument for economic management, central banks support this by keeping interest rates low, and inflation is higher than it would otherwise be. The potential for ‘fiscal dominance’ is something to watch for: the higher the debt levels, the more attractive this strategy is for governments.

More broadly, structural inflation pressures are likely emerging in a post-Covid world as I discussed recently: persistently tight labour markets, lasting frictions on globalisation, as well as costs of the green transition. This may be offset by stronger labour productivity growth, which I still think is likely. But we should prepare for higher inflation rates than seen over much of the past 20 years.

Given the politics of inflation, governments will need to actively manage these inflationary pressures.

This is my last note of 2021. Thanks very much for reading. I will be back in early January, with some thoughts on key developments to watch in 2022.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I deliver presentations and undertake engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

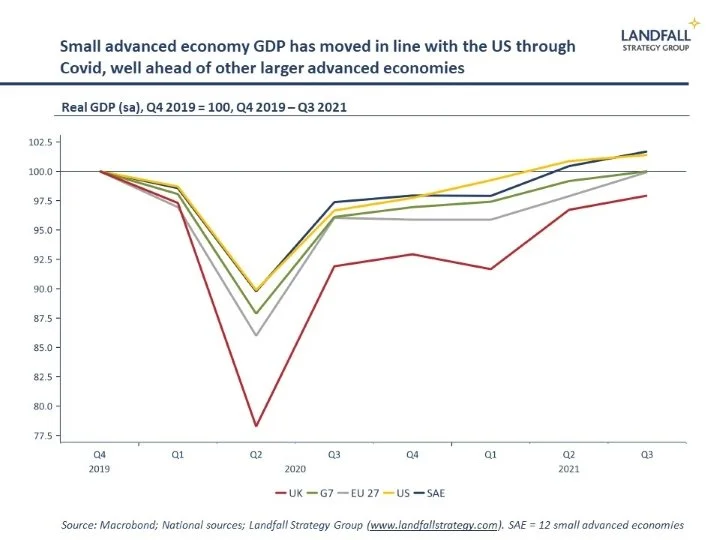

Chart of the week

GDP growth in small advanced economies continues to out-perform most larger advanced economies (excluding the US) through Covid. This is a function of generally strong Covid management, the ability to inject fiscal stimulus into their economies, as well as their exposure to strong world trade growth through the Covid period. As was also the case during the global financial crisis, small advanced economies have turned in a resilient economic performance.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling