On the agenda for 2022

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

This first note of 2022 provides my assessment of the big economic and political issues, trends, and risks in what is likely to be another bumpy, fast-paced year.

Covid doesn’t end

The past two years have been powerfully shaped by Covid, and Covid will also play a major role in 2022. Although the more contagious but seemingly less severe omicron variant looks to be crowding out delta, we should not expect a ‘normal’ (pre-Covid) year in 2022 across advanced economies.

Endemic Covid, with new variants likely, means some ongoing domestic and border restrictions as well as regular booster programmes (Israel has just started a 4th shot programme). The response to omicron reminds that reopening will be a stop-start process. This will create ongoing disruptions to supply chains, labour markets, and exposed sectors, even if the economic costs will be less severe than in 2020 and 2021.

It is the countries that have performed best through the pandemic that will likely lag in opening up because of higher levels of national risk aversion – the ‘winner’s curse’. Asian countries will be slower to open up than elsewhere: I am not expecting China to open its borders in 2022, and countries like Australia and New Zealand may find it difficult to fully reopen borders.

Inflation & a new macro policy regime

One of the big global economic uncertainties is the trajectory for inflation, and the associated policy responses. I expect inflation to moderate through 2022: a rotation of consumer spending back towards services, global supply chain pressures moderating, a weakening/negative fiscal impulse, as well as monetary policy action.

Even so, inflation is likely to remain higher than it has been over much of the past decade. And there are clearly risks – from wage pressure due to tight labour markets, higher inflation in the services sector, as well as ongoing supply side frictions in the global economy. Inflation will be a major political issue for several governments over the next year.

Many central banks are now moving to tighten policy. However, interest rates are not likely to rise by as much as in previous inflation cycles – due to high debt levels, preferences for a high pressure economy, and so on. It seems likely that real interest rates will remain negative, continuing to lend support to asset prices.

2022 is likely to continue to see a new macro policy regime emerging, with high government debt levels, as well as relatively high government spending and investment, supported by accommodating monetary policy.

Increasing domestic political risks

With the exception of the UK, politics in most large developed countries functioned better in 2021 (at least since January 6) than in the few years prior. But domestic political risks are rising. For one thing, governments will have to manage the increasingly fraught politics of Covid restrictions two years into the pandemic.

And there are several specific political events. In Europe, watch for the French Presidential elections in April (Mr Macron still favoured, but Ms Le Pen and other far right voices are popular) and the Italian elections (with a possible change in role for Mr Draghi). Both elections will have a broader impact across Europe. And a leadership change in the UK this year is more likely than not, along with ongoing political and constitutional uncertainty.

In China, President Xi is setting up for a norm-breaking third term at the 20th Party Congress in November. This looks settled, although Chinese politics is a black box and there are wild card political risks.

But the US is probably the biggest source of domestic political risk this year, a year on from the violence on Capitol Hill. Congressional mid-term elections are held in November, with the Republicans likely to make major gains. But there are risks around the legitimacy of the election results. Do defeated candidates accept the results, or do we see a re-run of the 2020 Presidential voting chaos? And can the Supreme Court mediate these disputes? The relative quiet of the Biden Administration should not make us forget about the underlying political dysfunction in the US.

Global economic fragmentation

Global merchandise trade flows have been robust through Covid, supported by the strong global recovery and the rotation of consumer demand towards goods. This is likely to moderate through 2022 – offset by a partial recovery in international tourism.

But the bigger set of issues to watch in 2022 will be whether the pace of decoupling with China accelerates. The economic case for decoupling (higher labour costs, more resilient supply chains) will continue to build but at a gradual pace; and offset by the attractiveness of investing in China to serve Chinese consumers.

It is political factors that will push the pace of decoupling, particularly in technology and other sensitive sectors. Expect more delistings, investment restrictions, and ending of commercial relations in these strategic sectors, as both China and Western economies look to strengthen strategic autonomy and reduce exposure.

And there will be growing pressure even in non-sensitive sectors. Western firms will find it hard to simultaneously manage stakeholder expectations in China and in their home markets; and governments are legislating restrictions on supply chains (eg banning inputs from Xinjiang).

Economic fragmentation is likely to accelerate through 2022, requiring governments, firms, and investors to make choices to manage their exposures. International commerce is increasingly a branch of geopolitics.

Shifting preferences on climate change

The COP26 meetings in November made some progress, but were widely seen as inadequate. This is not surprising, given the deeply political nature of the process. Increased ambition from governments is likely over time – although the current political response to high energy prices in the US and Europe shows the limits to what elected governments will do if it means higher costs.

But consumer and investor preferences on emissions have begun to move quickly through the pandemic, reinforced by growing evidence of a changing climate. 2022 may see more rapid changes in behaviour, in areas from transport (less flying) to deliberately buying less emissions intensive goods and services. This will vary across geographies and by demographic cohort, but this bottom-up action is likely to apply more pressure on firms and government to act more aggressively.

And accelerating technological progress is supporting these changed preferences: reducing the costs – and increasing the feasibility – of a rapid green transition, in areas from precision fermentation of food to green hydrogen that can decarbonise industry.

Geopolitical rivalry

2021 ended with rising tensions in Ukraine, the Taiwan Straits, and elsewhere. I think significant armed conflict is unlikely in 2022, but it is not impossible.

China will likely want stability through 2022 in the run up to the Party Congress meetings in November, making an invasion of Taiwan unlikely this year. But further Russian aggression in Ukraine is more likely, with Russia clearly testing US/NATO resolve by creating options for another invasion.

More broadly, we should expect ongoing testing of Western seriousness and credibility by China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and others (and possibly with some tacit coordination). The Afghanistan withdrawal raised questions about the competence and commitment of Western countries. And short of direct military conflict, hybrid warfare, disinformation campaigns, and offensive cyber measures (the topic of a sobering book I read over Christmas) are likely to continue.

These geopolitical risks should be taken seriously. Stepped up conflict (military or otherwise) that involved the big powers would have a substantial impact on the global economic and political system. It would rapidly accelerate economic decoupling through trade and investment sanctions, and the collapse of economic flows.

Technology & a productivity renaissance

To finish on a positive note, I continue to expect improved productivity performance across advanced economies in 2022 and beyond on the back of an accelerating pace of advances in innovation and technology.

Labour productivity growth has been in sustained decline across advanced economies over the past several decades. But Covid has strengthened incentives around business investment in technologies and new business models (automation, digital, etc). And business investment in intangibles has been strong. To the extent that accelerated, at-scale investment is sustained (which I think is plausible), it is possible that – combined with a high pressure global economy – productivity growth will rise.

And new disruptive technologies are developing quickly that could have a productivity impact over the next several years: from AI and quantum to genomics and robotics (discussed in another book I read over the Christmas break). These developments will generate new investment opportunities and require firms to adapt their business models to respond to competitive pressures. So in 2022, watch for the disruptive effect of new technologies.

Let me know what you think about what is important for 2022. And I look forward to engaging with you on these issues in the year ahead.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I deliver presentations and undertake engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

Chart of the week

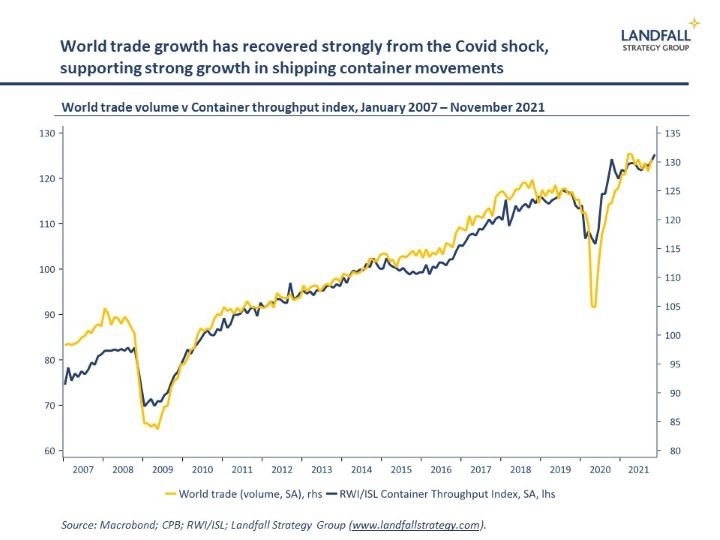

World trade has recovered strongly from the Covid shock. Merchandise trade volumes to October are holding at levels well above pre-Covid levels, due in part to the rotation of consumer demand towards goods (and away from services) during Covid - as described in the last ‘Chart of the week’. In turn, this has supported strong growth in shipping container throughput - sitting at record levels in November, despite the logistical constraints at ports. This also explains the surge in container shipping prices.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling