The exaggerated death of globalisation

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Globalisation is changing its shape. To take just a few recent examples in addition to the ongoing US/China economic tensions: the US and EU are weighing sanctions on Russia if it invades Ukraine; China continues to squeeze Lithuania for its support of Taiwan; and the Biden Administration has proposed the preferencing of US-produced electric vehicles. On the plus side, the world’s largest FTA (RCEP) went into effect on January 1.

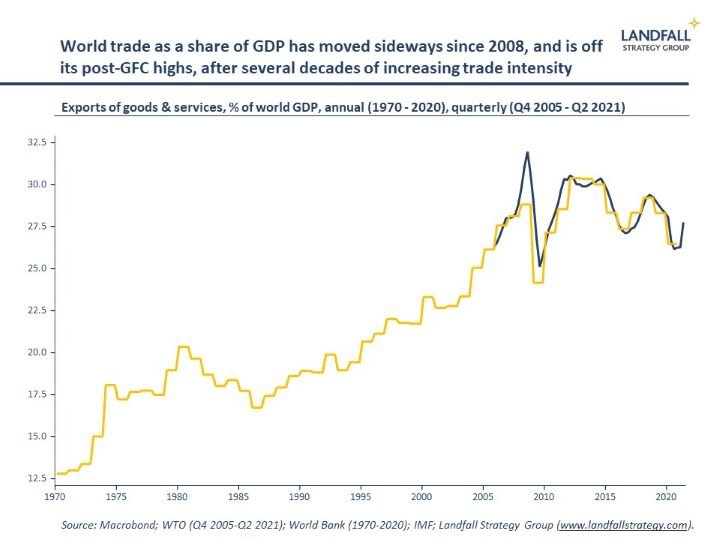

Many obituaries for globalisation have been written over the past two decades. And yet world trade as a share of GDP has declined only modestly over the past decade, after several decades of strong increases.

And globalisation has been resilient through Covid. World trade volumes are above their pre-Covid levels, and continue to grow, partly due to the rotation of consumer demand towards goods during Covid. Exports of services (international tourism) cratered during Covid, and FDI flows weakened, but both are likely to strengthen.

But structural change is underway. After 30 years of ‘hyper-globalisation’ we are moving into a new globalisation regime, a transition accelerated by the pandemic.

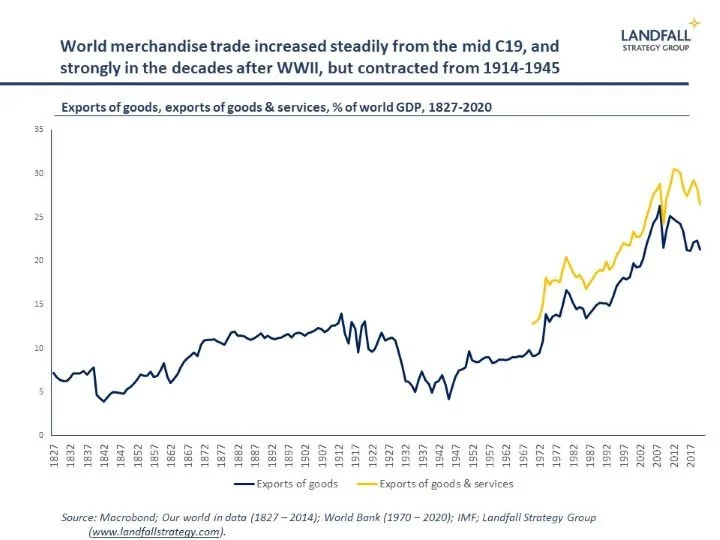

History shows that the globalisation model is a function of the global economic and political context. Hyper-globalisation was enabled by the extension of the of rules-based multilateral system after the Cold War, the emergence of China and other emerging markets, and the development of technology-enabled global supply chains.

But this international economic and political context is changing. This new globalisation regime will be more fragmented, with a globalisation that is more regional, more political, and shaped by big power rivalry.

The economics of globalisation

First, the economics of globalisation are shifting. Labour costs have been rising in many emerging market production platforms, making the labour cost arbitrage opportunity less compelling. Indeed, unit labour costs in China have converged rapidly towards those of advanced economies.

And technologies like automation and 3D printing are supporting the geographic compression of supply chains – by reducing the importance of high labour costs in advanced economies. Greater localisation is likely. And the costs and risks associated with long supply chains are increasingly influencing location decisions.

These commercial incentives are reinforced by the growth in regional trade deals that preference regional trade and investment flows.

The high water mark in far-flung supply chains has likely been reached. But re/near-shoring will be sector-specific, and gradual. Indeed, there has been relatively little at-scale relocation of activity – and the average distance of trade has not yet reduced markedly.

The powerful economic incentives around globalisation mean that many firms will maintain an international footprint. Firms may substitute FDI for trade, with investment in offshore production capability that is closer to the end consumer (e.g. European firms manufacturing in Asia for Asian consumers). A different composition of global flows is likely: a reduced share of goods, but more services, investment, and knowledge/data flows.

The politics of globalisation

But if the economic factors operate gradually, political factors are likely to be more disruptive.

The domestic political consensus in many large advanced economies around globalisation has changed. National governments are imposing more restrictions on trade, investment, and migration flows.

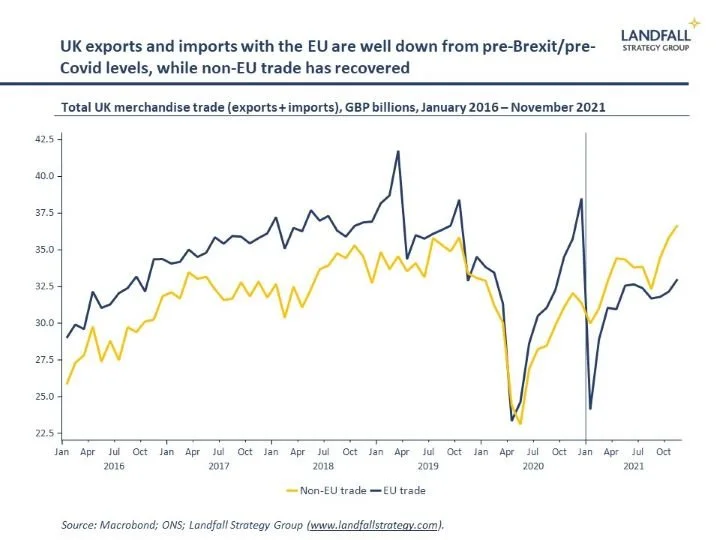

These political frictions will increasingly constrain the ability of firms to operate across global markets, increasing costs and reducing efficiency. Consider, for example, the impact of Brexit frictions: total UK trade with the EU is well below pre-Brexit levels, whereas non-EU trade has recovered more strongly.

Geopolitical rivalry between the West and China is also driving changes in globalisation. Although trade with China is at record levels in many advanced economies, investment flows to and from China are under pressure - particularly in technology. We have likely reached the high water mark in China’s integration into the global economy: China is adopting a more inward-looking set of economic policies, and Western economies are implementing tougher stances on trade and investment flows with China.

From ‘America First’ to China’s dual circulation policy and the EU’s ‘strategic autonomy’ agenda, governments are more inclined to promote national champions in areas from pharmaceuticals to sensitive technology.

Beyond this, there are many examples of large economies (China, US) applying various trade and investment sanctions on countries with which they have political disputes. And big power rivalry is weakening the ability of the WTO to function.

These geopolitical tensions are deepening in intensity and broadening in coverage. Countries are increasingly prioritising strategic political considerations over near-term economic considerations. For many types of global flows, there will be a bias to engage with ‘like-minded’ countries in order to reduce geopolitical risk exposures.

Implications

There are clearly challenges. But the historical record suggests that globalisation has been relatively resilient, with the obvious exception of the period covering the two World Wars. And I expect this to be the case going forward, assuming we avoid global conflict and widespread protectionism.

Although world trade intensity has likely peaked (due to China’s domestic focus, contraction of global supply chains, political frictions), a pronounced unwinding of globalisation is unlikely. Trade flows will tend to be diverted as opposed to destroyed. And there is some globalisation upside in terms of increased cross-border flows of FDI as well as knowledge and data. Globalisation is a powerful force, and it is difficult to bottle up.

But there will be powerful changes in the nature of globalisation. It will be a more regional, fragmented model of globalisation: trade and investment flows will be shaped increasingly by geography and geopolitical rivalry.

Significant changes in business and policy models will be needed. Countries and firms should still be looking to run externally-oriented growth models, but they will need to adapt these models for the new context: from managing exposures to geopolitical risk to reconfiguring global supply chains.

Countries – notably small advanced economies – and firms that responded most quickly to the new opportunities and challenges of hyper-globalisation performed very well from the 1990s (and vice versa). The same will be true of the transition to this new globalisation regime.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I deliver presentations and undertake engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

Chart of the week

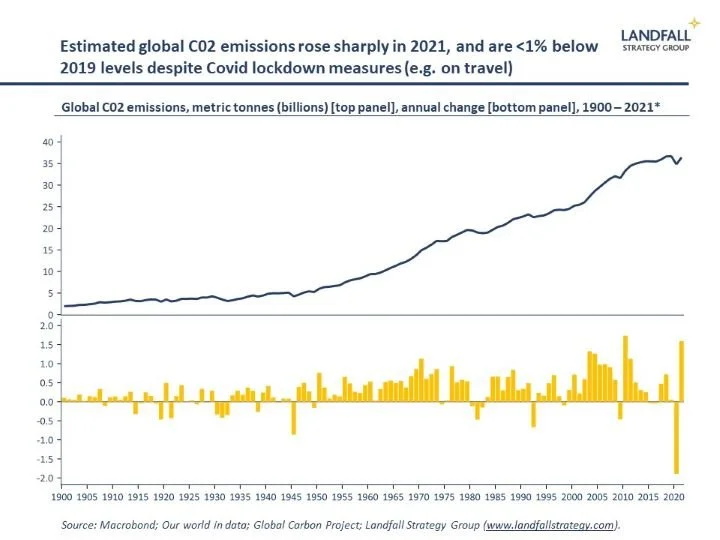

Global CO2 emissions rebounded sharply in 2021 as the global economy recovered, although they remain just below their 2019 peak. Substantial work needs to be done to drive emissions down to a pathway consistent with net zero. And the clock is ticking: 2021 was estimated to be either the fifth or sixth hottest year on record (estimates vary), with the last seven years the hottest ever documented. 2021 was 1.1 degrees above pre-industrial levels, not far away from the 1.5 degree threshold.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling