Europe on the front lines

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Just over two years ago, I relocated from one end of Eurasia (Singapore) to the other (the Netherlands). One reason for this move – after 11 fantastic years watching Asia and the world from Singapore – was to get a different perspective on global economic and political developments.

And despite spending much of this period in varying forms of Covid lockdown, being in Europe has provided a good view on changing global economic and political dynamics.

Although the centre of global economic gravity has been shifting inexorably towards Asia, and US/China is the single most important bilateral relationship, Europe sits on emerging fault lines in the global system. Dynamics at one end of Eurasia have clear echoes at the other. There are two reasons for Europe’s exposures.

Europe’s exposures

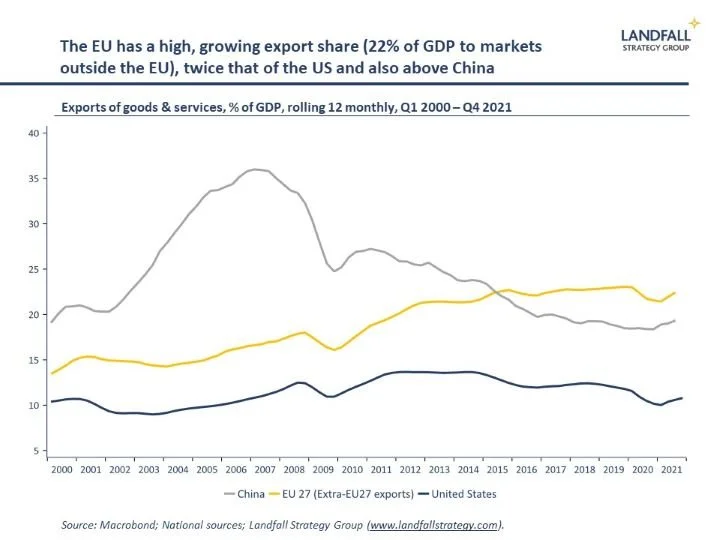

First, Europe is a highly open economy – with substantial exports and imports (outside of the EU27) as well as investment flows. As a share of GDP, these international flows are significantly higher than in the (similarly-sized) US as well as Japan and China.

This international presence is a source of economic dynamism. But in the context of geopolitical tensions increasingly playing out through economic channels, this is also a source of exposure. Indeed, the growing economic tensions with China are evident in Europe.

For example, China has recently sanctioned Lithuania after it strengthened relations with Taiwan (now the subject of a WTO complaint by the EU). And other countries, from Sweden to Norway have been on the receiving end of Chinese pressure. The potential for economic costs from bilateral political tensions is felt acutely in Europe because the EU/China trade relationship is the largest in the world.

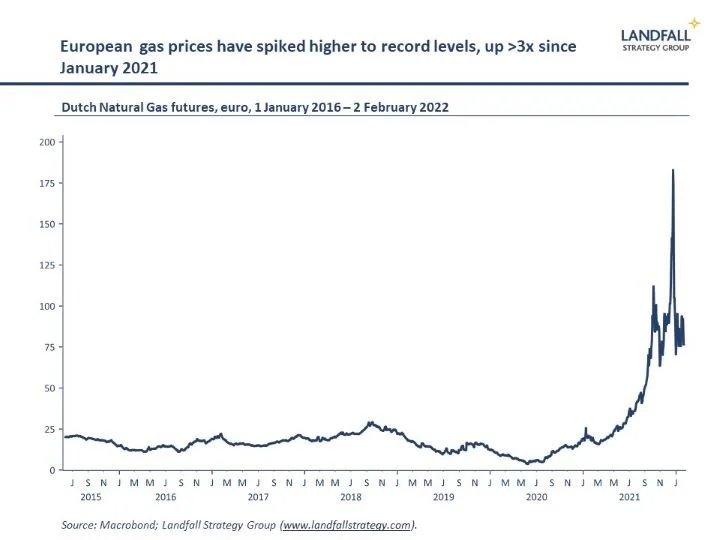

And Russia has been using economic leverage to impose pressure on Europe; restricted gas flows have led to record-high gas prices over the past several months in Europe. The IEA head recently said that Russia could increase gas deliveries to Europe by at least one-third, and linked tight supplies to geopolitical tensions.

The second reason is geography: Europe neighbours Russia, a country that is looking to reshape the regional political and security space (and beyond). This is most obviously seen in Russia’s current actions on the border of Ukraine (as well as its 2014 invasion). Even neutral Ireland, on Europe’s west flank, has found itself under unwelcome Russian pressure over the past week or so.

Although I think it unlikely, the risk of direct military conflict in Europe is as high as it has been for some time. But at a minimum, Russia is applying economic and political pressure, looking to exploit differences in Europe, and build a de facto sphere of influence across its neighbours. This has clear parallels with China’s behaviour in the South China Sea, as well as its threats to Taiwan and its actions in Hong Kong.

So Europe is currently ground zero for the weaponisation of international commerce as well as for pressures on the global political and security system. The way in which Europe responds will shape the way in which the global system evolves: from the fragmentation of the global economy to China’s perceived space to act on Taiwan.

Responding to a changed world

After an initial period of hopefulness/naivete, many European countries are becoming more hard-headed on these realities and are pushing back on Chinese economic and diplomatic aggression. Similarly, there is broad agreement on imposing economic and political sanctions on Russia if it escalates further in Ukraine.

This changed settings are not the default preference of Europe, but global realities have caught up with it.

‘You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you’ (Leon Trotsky)

In economics, there is an increased focus on strengthening economic resilience (‘strategic autonomy’) at national and EU levels – from energy markets to technology.

The EU’s Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with China is on hold after sweeping Chinese sanctions on European institutions; the EU is preparing new supply chain legislation, focused on human rights violations, which will likely catch China-exposed firms; and investment restrictions are being more widely imposed on Chinese firms. This is not yet decoupling, but there is a much more deliberate management of exposures.

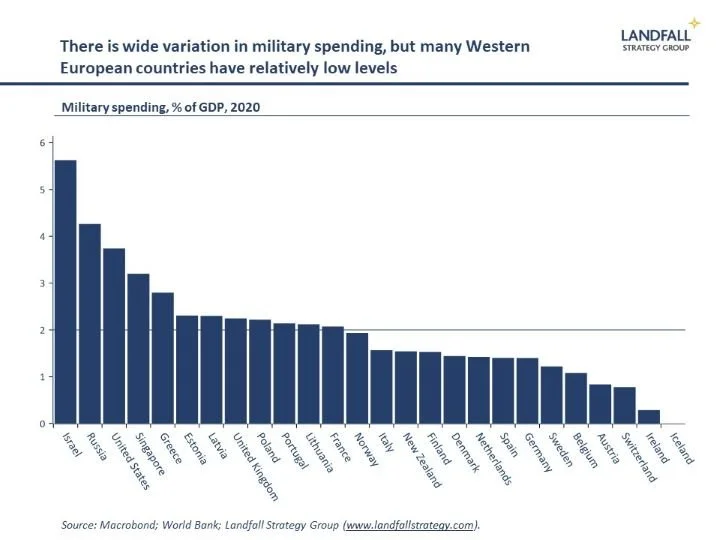

In terms of the security response, many European countries have committed forces or equipment to Ukraine and neighbouring countries. Across Europe, countries are looking to strengthen and update their military and strategic capabilities: several have developed Indo-Pacific strategies, for example. The political and public consensus on these issues is shifting.

However, there is significant variation across European countries in the strength of their responses to the economic and political dynamics. The Ukraine situation has illuminated some of these differences. The Netherlands and the UK, as well as several central and eastern European economies, have been punchier in their response to the Ukraine tensions than Germany (note also Germany’s support of Nord Stream 2)

Similar, large countries with big economic exposures, such as Germany and Italy, have less inclined to take tough stances on China. Smaller economies, with big exposures but acute sensitivity to big power politics, have often been quicker to act.

These differences across countries make it very difficult to establish a common EU approach to geopolitical issues (although the current tensions have made NATO more attractive to non-members such as Sweden and Finland). Indeed, the US has been central to mobilising action on Ukraine.

The implication is that much of the economic and security response will take place at national level and in coalitions of the willing - where interests and values align and consensus can be formed - rather than at EU level.

Europe as a swing state

Overall, Europe should be watched carefully for its response to emerging economic and political pressures. The geography and relatively closed economy of the US has made it easier for it to adopt hawkish approaches on China and Russia than for Europe. But as a highly open economy, European actions are a good barometer for the state of the global economic and political system.

If Europe responds to current economic and political pressures in a more assertive manner, this will powerfully shape the global system: signalling greater fragmentation of the global economy, a greater focus on resilience, and increased investment in hard power. This may not be Europe’s preference as an outwardly-focused economy, but it seems the likely direction of travel given current realities across Eurasia.

Even for countries on the other side of the world, decisions that are taken in Europe will have deep consequences.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I deliver presentations and undertake engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

Chart of the week

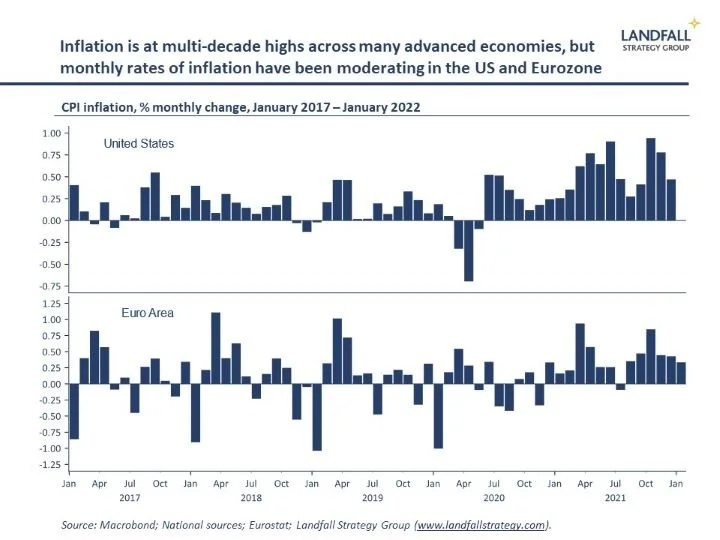

Eurozone inflation hit a record of 5.1% in the year to January; US inflation was 7% in the year to December; and inflation across the OECD was 6.6% in December, a 30 year record (although still below Turkey’s latest reading of 49%!). There are concerns that central banks are behind the curve, and that a wage/price spiral is looming. But my view remains that the surge in inflation will moderate over the year as Covid-related stresses reduce. Indeed, the monthly inflation readings in the US and the Eurozone have been softening since October – at the least, indicating that inflation pressures are not accelerating.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling