The superpower of successful countries

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

As countries from Sweden and Denmark to the UK begin to lift remaining Covid restrictions, it is useful to look at the countries that have done ‘best’ in managing the Covid crisis – and why.

The caveat is that Covid will remain with us for some time so things may change. I have noted the winner’s curse: countries that do well in one phase of Covid have often under-performed subsequently. But after almost two years of the pandemic, some assessments can be made.

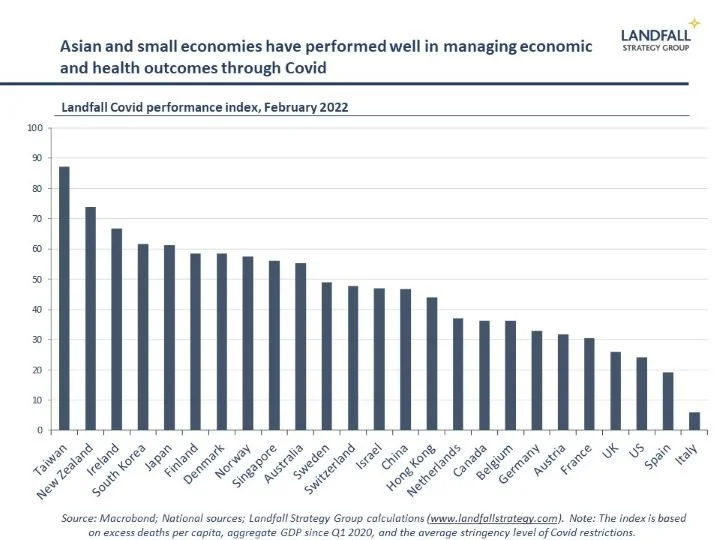

To put some structure on this, I construct a simple index of overall performance in managing Covid. This index includes measures of excess deaths per capita over the Covid period; strength in GDP performance since Q1 2020; and the average stringency of Covid restrictions.

There is some geographic variation, with many Asian economies – from Taiwan to Singapore and New Zealand – having done well in keeping Covid cases and deaths down, through tough approaches to containment, as well as generating strong economic outcomes. Looking forward, however, it will be challenging for some Asian countries to relax restrictions – from China and Hong Kong to New Zealand. Some of this strong Asian performance may weaken over the next year.

There is also a national scale dimension. The Nordics (note Sweden) and other small northern European countries (note Ireland) are also near the top of the rankings. At the other end are large countries like Spain, Italy, the UK, and the US. Overall, small countries have tended to do better – although with some variation (note Austria, Belgium).

Institutions matter

And there is an underlying institutional framing to performance. I have previously discussed the positive correlation between measures of political and social institutions and Covid approaches and outcomes across advanced economies. These characteristics have more explanatory power than pre-Covid measures of pandemic readiness, which ranked the US health system in first place – and countries like Singapore and New Zealand towards the bottom.

This institutional framing received further confirmation in a study published in The Lancet last week. This global study found that ‘Measures of trust in the government and interpersonal trust, as well as less government corruption, had larger, statistically significant associations with lower standardised infection rates’ (as well as with vaccination rates). ‘Getting to Denmark’ in terms of levels of trust would have reduced global infection rates very substantially.

Strong political and social institutions have made a valuable contribution to good Covid outcomes. And it is small advanced economies that perform well on these institutional and trust measures, going some way to explaining why they have managed relatively well through the Covid crisis.

Beyond Covid

Covid is not the only domain in which institutions shape performance. There are well-documented links between the strength of political and social institutions in generating strong, sustained economic performance (state capability, government accountability, absence of corruption, trust in institutions, social trust, and so on). Singapore is a canonical example of a country that has done this well, Argentina an example of a country that has not.

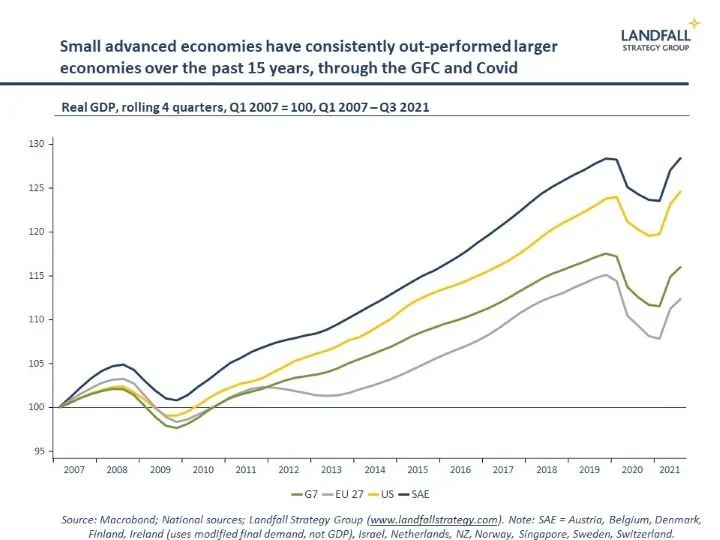

The strength of institutions and trust in small advanced economies will provide them with an increasingly strong competitive advantage. Although obituaries have been written for the small economy model given the challenging global environment, small economies continue to consistently out-perform larger economies. This resilient performance is importantly due to high quality policy choices and agility.

The small economy experience also shows that trust in institutions is not fully exogenous: it can be earned (or lost). Institutional trust is high in small economies because their political institutions have delivered good outcomes: GDP growth, employment, social mobility, and so on.

For example, many small advanced economies – which are deeply exposed to the global economy – have managed globalisation well. They have invested to capture the benefits of globalisation, while setting policy (social insurance, labour market policy) to manage the costs and risks. As a consequence, a political consensus remains in favour of openness.

In contrast, larger economies like the US and the UK have not managed these pressures well even as globalisation and technology have reached further inside their economies. The pressures on labour markets and income inequality have grown, leading to a political backlash on issues from trade to migration – as well as broader challenges to their political systems.

In what will be a deeply demanding global context ahead – from climate change to disruptive technologies and geopolitical rivalry – it is economies with strong institutional capabilities and high levels of trust that are likely to perform best. These systems can set high quality policies that respond to the new context, and are able to respond effectively to increasingly frequent periods of crisis and stress.

The strength of social and political institutions – the ‘intangible infrastructure’ of successful economies – is the single most important characteristic that I look to as a guide on future economic outcomes (as well as medium term market performance).

A democratic recession?

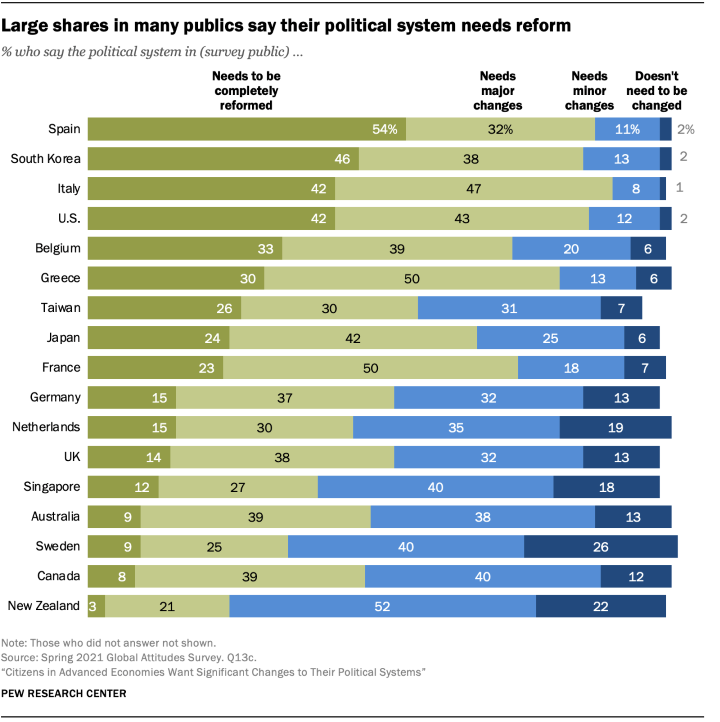

But the global outlook for this intangible infrastructure is concerning. A Pew survey in December found that substantial shares of populations in many democracies favoured substantial changes to political systems because the current arrangements were not delivering.

And the Economist’s annual Democracy Index, released this week, reported a further weakening in the health of democracy around the world. Again, small advanced economies dominate the rankings, taking the top seven places, led by the Nordics and New Zealand.

Similarly, measures of institutional trust have been declining around the world. Covid restrictions have taken their toll on social and institutional trust in many countries. And the redistributive effects of issues from inflation to new technologies and managing climate change will place further pressure on political systems over the coming period.

Those economies that can manage these pressures best, and maintain high levels of trust and institutional capability, will perform best in what will be a period of disruptive change ahead.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I deliver presentations and undertake engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

Chart of the week

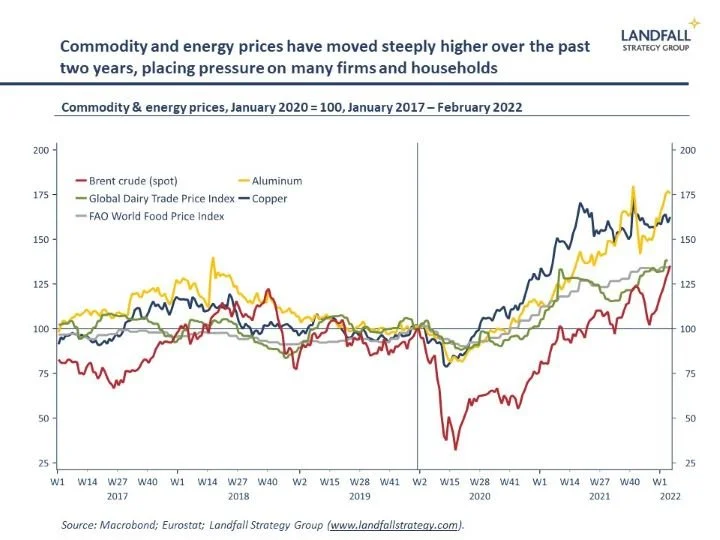

One of the reasons for the surge in inflation over the past several months is the steep increase across a broad range of energy and commodity prices. Industrial metals like copper and aluminum are up by >60% since January 2020, food prices are up by over a third, and oil prices are up by >3x since Q1 2020. This is squeezing household budgets as well as raising the cost of inputs for firms. It is becoming a major political issue for governments around the world. The rising prices are due to a complex of reasons from a strong recovery, various supply side constraints (weather, lack of investment, global supply chain frictions), as well as geopolitical tensions (oil and gas).

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling