The end of the beginning

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

I’m writing on one of the darkest days in Europe for decades, hours after Russia launched a full invasion of Ukraine. It would be tempting to refer to Ms Merkel’s characterisation of Mr Putin as a man using 19th Century methods in the 21st Century. Except that the forces being unleashed have an unfortunately 21st Century flavour to them: big powers coercing smaller states, a fragmenting global system, and the weaponisation of international commerce.

Geopolitical tensions have been building for some time, as Russia, China, and others challenge the global economic and political system. Many Western countries – comfortable in the post-Cold war environment – have been slow to recognise the magnitude of this challenge.

Attitudes have been shifting on China over the past few years. But it is Russian behaviours this week that have crystallised what is at stake. After a period of tentative Western recalibration over the past several years (some sanctions, decoupling), we are now likely to see a more concerted pushback to the various challenges to the rules-based system.

As Winston Churchill said 70 years ago after the second battle of El Alamein, ‘Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning’.

There is much uncertainty on how the Ukraine crisis will develop. But, drawing parallels with the structural impact of the Covid crisis, I discuss three global dynamics that these events are unleashing.

Countries & choices

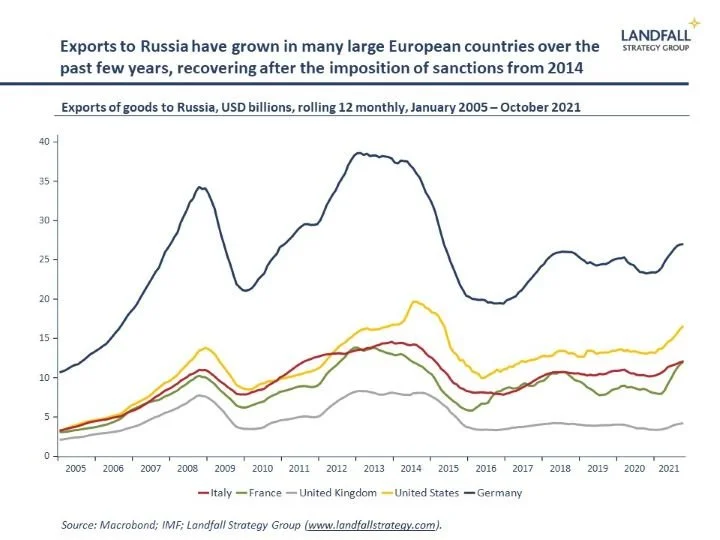

Just as the Covid shock exposed national strengths and weaknesses, so too the Ukraine crisis exposes the extent of strength and coherence of the West. In particular, this crisis crystallises the need for countries to make strategic choices. Many countries in Europe (and elsewhere) have tried to avoid making choices between their economic and strategic interests – seeking to capture economic value from commercial relationships with Russia, and engaging with Russia despite its repeated transgressions over the past decade.

But choices cannot now be avoided. And despite concerns that Europe would respond weakly, the EU has landed on a good initial set of sanctions; weaponry has been provided to Ukraine; Germany has (finally) decided to cancel Nord Steam 2; and the UK has now announced a tough set of sanctions on Russian capital, individuals, and aviation (after an initially underwhelming response). The US is also imposing measures.

Much more needs to be done, but this has been an encouraging initial response given Europe’s exposures to Russia (energy, trade). I wrote recently that Europe is on the front lines of structural change in the global system because of its highly open economy, and that its behaviour is a useful global barometer. And there is active debate on further EU sanctions on Russian oil and gas and Russia’s banking system. There is not yet consensus on these issues, but more aggressive measures are likely from the EU.

This represents a convergence to the perspective of small economies on Russia’s borders – notably the Baltics and Finland – that have been warning of Russian risks for some time.

Beyond Europe, the US is said to be building a coalition of Asian economies that will stop high tech exports to Russia; and Australia and Japan have announced sanctions. Turkey has urged Russian restraint. But India to China have been reluctant to openly criticise Russia. And several Asian countries – often exercised about issues of sovereignty – have been notably quiet.

After a decade (and more) of prioritising near-term economic benefits (energy supplies, Russian market access, investment flows), Russia’s violent adventurism is a forcing event for countries to make overdue hard strategic choices about their positioning. More Western countries are now prepared to bear costs in order to support the rules-based system.

Accelerating global fragmentation

It is commonly observed that Covid accelerated a range of economic and political dynamics, from the use of technology to supply chain localisation. Similarly, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will accelerate the ongoing fragmentation of the global economic and political system.

In a direct sense, further sanctions on Russia, together with choices made by firms and consumers to reduce their exposure to Russia, are likely to lead to a decoupling of Russia from the global economic system. Russia will remain an important commodity exporter – although countries will be developing alternatives, particularly in energy – but its high-tech sectors will be deeply challenged, as well as its financial sector (particularly if Russia is removed from SWIFT).

And more broadly, this will likely accelerate decisions by Western firms to reduce exposures to other countries with which there are geopolitical tensions – most notably China. Previous notes have discussed the decoupling that is underway with respect to China. Trade and investment restrictions, as well as shifting consumer preferences, are leading an increasing number of firms to reduce China exposure. This behaviour is being reinforced by the changing economics of global supply chains.

The Russian tensions will increase the salience of these issues, likely leading to a more rapid decoupling of Western firms from China. Europe has lagged the US in this process, partly because of Europe’s more acute economic exposure. But the hard choices that the Ukraine crisis will force are likely to contribute to a further hardening of European approaches to China engagement.

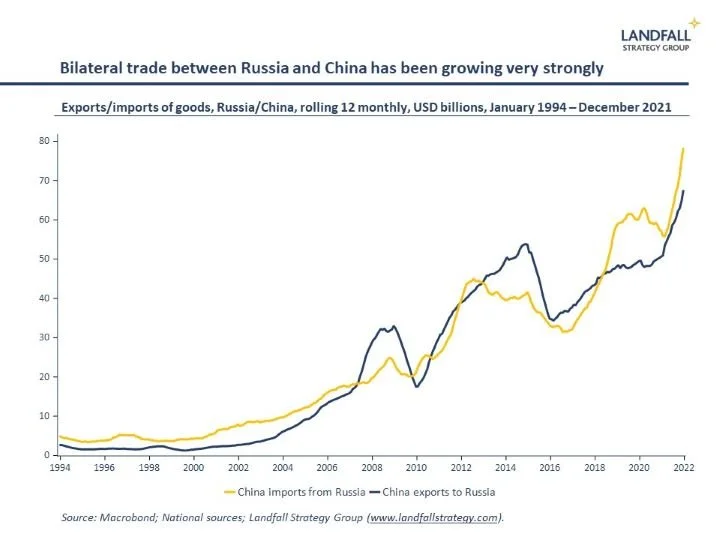

This is likely one reason why China is not thrilled by Russia’s behaviour. Although it has not criticised Russia in public, neither has it been supportive of the invasion. But despite this, it is likely that China and Russia will continue to strengthen their economic relations in response to this Western decoupling (exactly 50 years on from President Nixon’s visit to China, to prise China away from the Soviet Union).

A systemic global shock

The Covid shock started with a small outbreak in Wuhan, before going global. Similarly, the events across Ukraine will have a global impact.

For example, the behaviour of Russia and the nature of the response by the US and Europe, will impact on how China approaches its territorial disputes – notably its Taiwan claims. The way that the Ukraine crisis plays out will set a precedent, and is being watched carefully in Asia.

And this crisis will have a major global economic impact. Although Russia’s GDP is smaller than the Benelux economies, the widespread sell-off across global equity markets (ex-US) on Thursday gives an indication of the concern about the economic consequences of the conflict and accompanying sanctions on Russia.

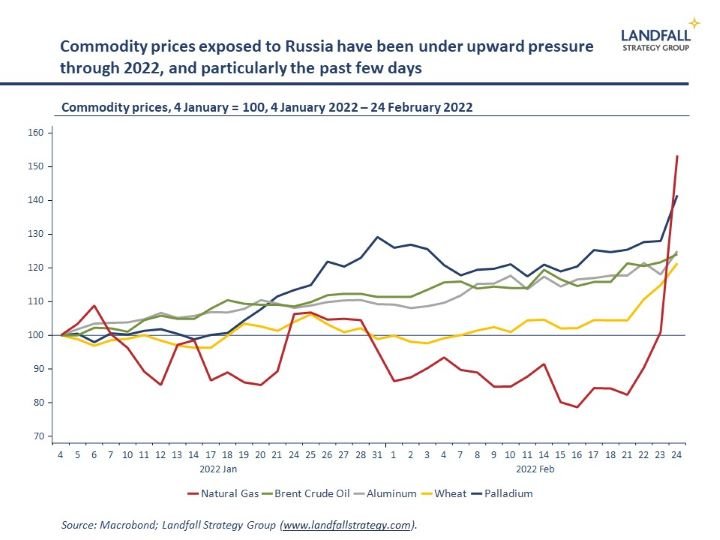

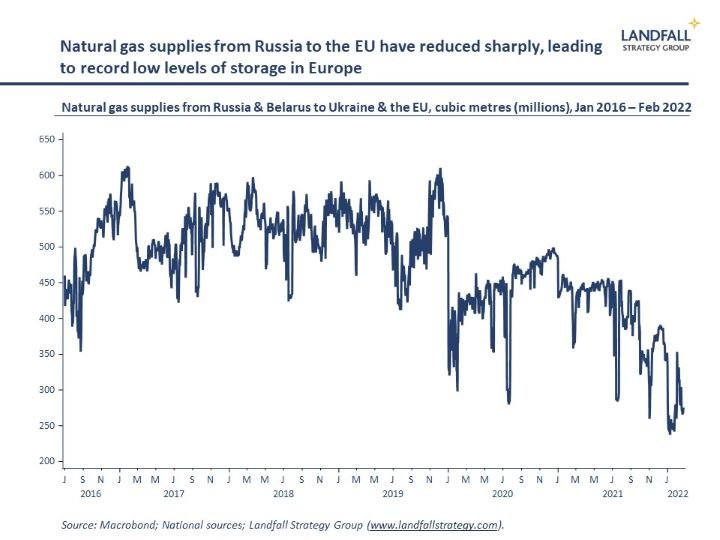

There are several channels, most obviously oil and gas prices. Russia accounts for ~8% of global oil exports, which will be sanctioned and constrained – oil prices have been moving higher and spiked up again this week. Russian gas supplies to Europe, already limited by Russia (see ‘Chart of the week’, below) will likely reduce further – putting upward pressure on already sky-high gas prices in Europe. Over time, energy systems (renewables, nuclear, LNG imports) can be developed to reduce reliance on Russia. But this will take several years at least, involving big costs.

Russia is also a significant global exporter of commodities such as platinum, palladium, and aluminium. This makes Russia an important part of global supply chains in areas from semiconductors to cars.

Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of agricultural products; together they account for ~30% of global wheat exports. And Russia is the world’s largest exporter of fertiliser. Any sanctions or disruptions to exports in this space would exacerbate the current surge in global food prices.

And there are other global economic risks: the disruption of fly-over routes from Europe to Asia, stepped up cyberwar measures (with the potential for spillovers), and so on.

Taken together, these exposures mean that economic escalation could do substantial damage – both to an already weak Russian economy (Russia’s equity markets were down by 33% on Thursday, down by ~45% since early January) but also to the post-Covid global economy that is already grappling with inflation, global supply chain pressures, and so on.

A watershed moment

The Ukraine invasion is a watershed moment, and will have far-reaching consequences for the global system. It will likely lead to more intense strategic competition between political blocs, greater economic decoupling, as well as substantial economic costs and frictions around the world. We should not under-estimate how significant this week’s events are. Governments, firms, and investors will need to quickly adapt to the realities of this emerging world.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I deliver presentations and undertake engagements on global economic, policy, and political dynamics, and their implications, to policymakers, firms, and investors. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these opportunities.

Chart of the week

European gas prices are at record highs in large measure because of reduced gas flows from Russia to Europe. Gas flows are ~50% lower than would be expected. As a consequence, natural gas storage is at record lows for this time of year, also ~50-60% below last year’s levels. These reduced gas flows are widely seen to be a political decision to exert pressure on Europe, rather than being due to limits in production. Further reductions in gas flows are possible if economic sanctions are imposed.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling