War by other means

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Earlier this month, President Biden announced the final withdrawal of all US troops from Afghanistan by September after almost 20 years of combat operations. Shortly before this, the President hosted a CEO summit on strengthening semiconductor supply chain resilience – and allocated $50b to building US semiconductor manufacturing capability, partly to push back against China.

This reflects a broader policy focus to global competition, which includes strategic economic policy as well as the military.

War is a mere continuation of policy by other means (von Clausewitz)

Artificial intelligence is the future… Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world (Vladimir Putin)

A threatening world

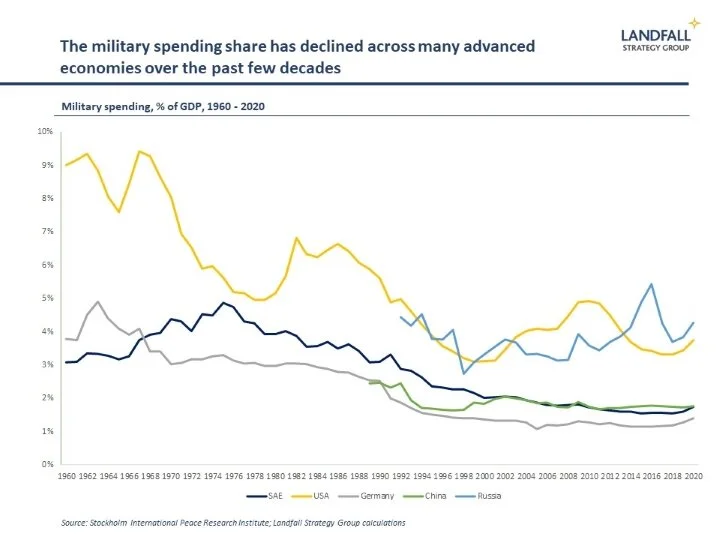

Data released on Monday by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute reported a 2.6% increase in global military spending in 2020, even in a period of economic crisis, to almost US$2 trillion. Security risks are assessed to be increasing by many countries.

Indeed, also in Stockholm, Sweden is raising its defence budget by 40% up to 2025 in response to threats from Russia and elsewhere. And Swedish firm Saab announced strong earnings during the week on the back of increased demand for defence. The downward trend in military spending/GDP after the Cold War looks to be ending.

Investment in defence remains important for many countries, particularly those in tough neighbourhoods. Eastern Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean, and East Asia are just a few locations where small economies have high levels of military spending.

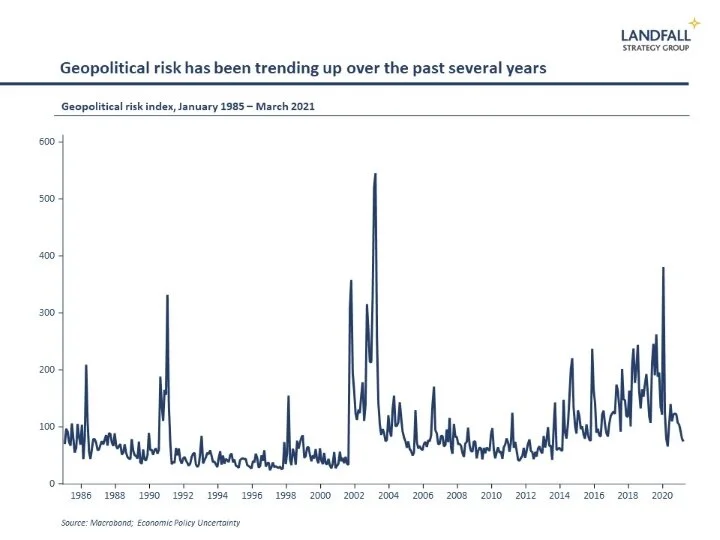

From Taiwan to Ukraine, it is not difficult to identify geopolitical risks around the world. Indeed, measures of geopolitical risk have been increasing over the past several years.

The rise of China is a key dynamic at work, creating tensions in the global system. You don’t need to buy into the Thucydides Trap argument to recognise the risks in great power competition.

Managing economic and political relations with China is increasingly challenging for advanced economy governments and firms. And more countries, large and small, are pushing back deliberately.

This competition will extend beyond traditional measures of hard power. China is deeply integrated into the global economy, in a way that the Soviet Union was not during the Cold War. China is developing leading positions in advanced industries, and is pursuing an aggressive strategy to build self-sufficiency (such as its recent ‘dual circulation’ policy).

From hard power to the commanding heights

Strategic competition between big powers will increasingly involve broader economic domains. Key vectors of competition will include technology (AI, quantum, semiconductors), finance (reserve currency, international payments system), infrastructure, as well as strategic supply chains (energy, food, pharma).

It is the search for control of the commanding heights of the C21. Contra to Norman Angell’s infamous pre WWI argument that war was impossible because of economic integration, it is economic integration that is a key aspect of international tension.

The legacy of Mr Trump’s trade wars are not tariffs but policies such as bans on technology exports to China and constraints on Huawei in 5G networks. ‘Technology wars are becoming the new trade wars’ as an IMF paper recently noted.

If war is the continuation of policy by other means as von Clausewitz suggested, then increasingly economic and technological competition is the continuation of war by other means. This is the context in which to read Mr Biden’s recent announcements on semiconductors.

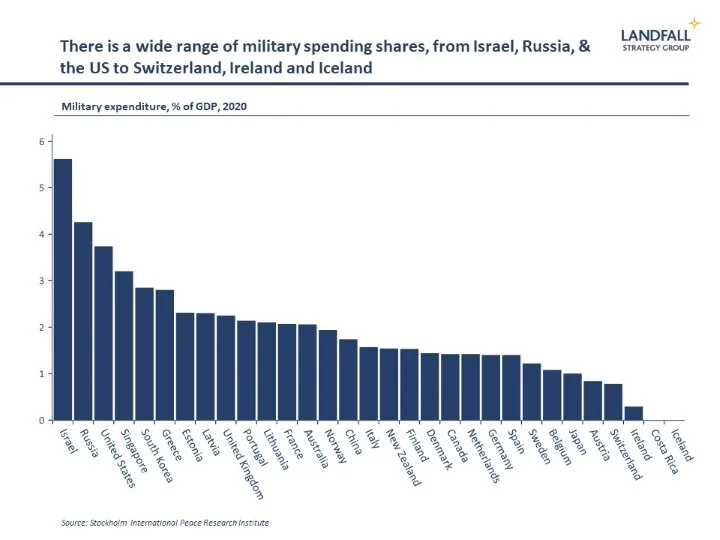

The implication is that substantial investments are needed to build leading capabilities. The US has many strengths. But it is hard for the US to compete effectively when it has declining life expectancy, crumbling infrastructure, huge inequalities, and a bitterly divided political system. Given the already high 3.7% of GDP spent on defence, addressing these economic and social issues should be a priority.

This seems to be the current direction of US policy. As President Biden stated in his address on Wednesday to Congress, ‘We can’t stop now — we’re in a competition with China and other countries to win the 21st century’.

Beyond the big powers

This changing nature of strategic competition will have implications beyond the direct protagonists. Big power competition will reach deep inside economies: the choice of communications platforms, restrictions on M&A, the shape of supply chains, and so on. For smaller economies, a key priority is to avoid being trampled in the contest.

There is significant variation in small economy approaches to defence spending, from Israel and Singapore to economies like Ireland, Iceland, and Costa Rica. This variation reflects their strategic (geographic) context. There will be greater demands for stepped-up investments and participation in security alliances, from NATO to the Five Eyes.

But there will likely be less variation in approaches to a fragmenting global economy in terms of trade, investment, and technology. Hard choices about positioning will need to be made, as it becomes less possible to separate commercial and strategic choices.

For example, small economies like the Netherlands that have emphasised openness are now adopting a more deliberate posture on technologies, including semiconductors. There are of course opportunities as well: Finland’s Nokia and Sweden’s Ericsson are alternative 5G suppliers.

And small economies can lead in terms of developing new rules of the game, as New Zealand, Singapore, and Chile have been doing with initiatives like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and DEPA.

Overall, this is a deeply consequential set of dynamics. The post-Covid economic recovery in advanced economies will likely have technology investment as a central feature. But the profile of these investments will be shaped by the emerging geopolitical context.

Small economies will need to develop a strategic posture that responds to new forms of global competition, including a core economic dimension. The global economic landscape will look quite different than over the past 30 years.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

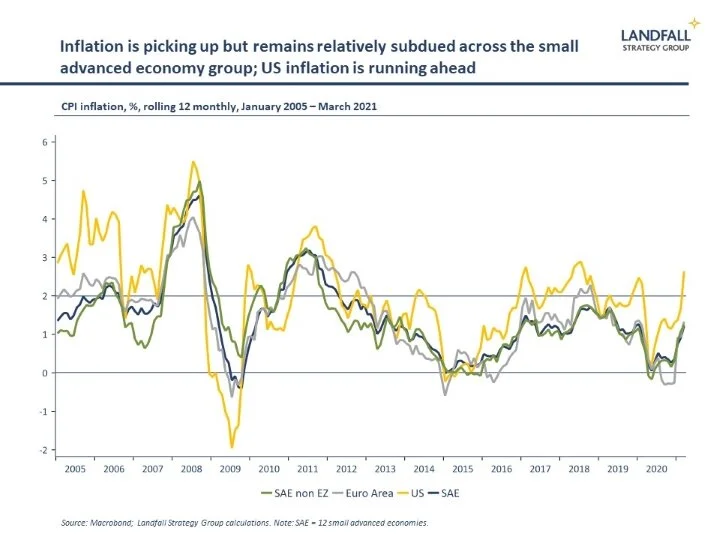

Inflation concerns are rising around the world, with a combination of an expected strong recovery, substantial macro stimulus, and supply side constraints. Inflation in the US is up to 2.6% in the year to March - although the Fed see these pressures as transitory. Elsewhere, it is hard to see systematic inflation pressures across the global economy. In small advanced economies, which are deeply exposed to the global economy with large import and export shares, the average inflation rate was just 1.2% in March. These data do not (yet) suggest a surge in inflation.

Around the world in small economies

The Biden Administration has proposed a global minimum corporate tax rate, which is attracting support from other large economies such as Germany and France. Small economies like Ireland and Switzerland, that have used corporate tax rates to strengthen their competitive position, are exposed. [Note: for subscribers to my Insight notes, I am currently preparing a piece on these international tax reforms.]

Denmark has built a strong position in renewable energy over the past few decades, and is investing to maintain its edge in an increasingly competitive space. Scotland is also transitioning from oil and gas to renewables.

Swiss/EU relations are challenged at the moment, with ongoing debate about the institutional framework to replace the 120+ specific agreements that currently govern relations between the EU and Switzerland. Some in the Swiss debate have taken inspiration from Brexit.

House prices have increased sharply across small economies over the past year. Swedish single family homes increased in price by 20% in the year to March, the fastest since 2005; New Zealand house prices were up by 24% in the year to March; and several others are up by double-digit numbers (Dutch house prices increased by 11% in the year to March).

The New Zealand Productivity Commission released its final report on growing frontier firms. The report is available here, and the contribution that I made (drawing on the international small economy experience) is available here.

International travel is opening up between some of the strong Covid performers. Travel between Singapore and Hong Kong resumes from May 26, and the Australia/New Zealand travel bubble opened up in mid-April.

Stockholm has created more tech unicorns per capita than any other region in the world except Silicon Valley. Other European tech hubs in the top 10 of VC invested include Amsterdam, Zurich, Espoo, and Helsinki.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling