Geopolitical competition & innovation

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Last week, the Biden Administration issued a formal advisory warning to US firms operating in Hong Kong. It said developments like the new National Security Law in Hong Kong meant that ‘the risks faced in mainland China are now increasingly present in Hong Kong’. The ‘one country, two systems’ approach, the formulation agreed for the handover in 1997, is de facto over.

Developments in Hong Kong often illustrate the state of the US/China economic and political relationship, as I have noted before. And recent developments suggest three broader insights on the state of the geopolitical environment.

Bearing the cost

First, neither the US or China show any sign of reducing tensions – with both being prepared to absorb the associated costs. The ongoing spread of Chinese political and legal approaches in Hong Kong is leading to an exit of meaningful numbers of Hong Kongers and foreigners, risking its status as a global hub.

Elsewhere, Chinese regulators unexpectedly restricted ride-sharing company Didi, sending its just-listed US shares down by ~25%. This will likely chill future Chinese listings in the US. And although President Xi recently claimed that he wanted a reset in China’s relations with the rest of the world, bilateral economic sanctions (e.g. Taiwan, Australia) and wolf warrior diplomacy continue. This contributes to ongoing weakening in China’s international reputation, according to the latest Pew survey.

A number of Western countries are also prepared to absorb the costs of more fractious relationships with China. The comprehensive investment agreement (CAI) between the EU and China was halted after sweeping Chinese sanctions against European politicians and institutions. The UK recently announced that it was reviewing the Chinese purchase of semiconductor firms. And Secretary Yellen dismissed the possibility of restarting the US/China Strategic Economic Dialogue.

These events suggest that a range of countries are willing to bear economic costs associated with this geopolitical rivalry. Under President Xi, China will likely continue with this approach for some time.

Indeed, China will argue that the costs are nominal – IPO activity in Hong Kong remains strong, for example, as are Western financial flows into Chinese markets. And bilateral US/China trade flows are growing healthily.

And the consensus policy view (particularly in the US, but more broadly) on China has changed from a focus on engagement to an explicit recognition of strategic rivalry. It is one of the few issues on which there is a measure of bipartisan agreement in Washington.

Economic rivalry: from defense to offense

Although there are obvious hard power dimensions to the rivalry between China and the US (and others), with military spending increasing, this is importantly a conflict that is playing out in economic, financial, and technological domains. It is war by other means. Both are aiming to build positions of strength in the commanding heights of the C21 global economy.

There has been a marked rotation of emphasis over the past year, particularly in the US, from defensive measures to more positive, forward-learning measures. The first stage of the economic rivalry, notably under the Trump Administration, was about imposing tariffs on Chinese exports, various economic sanctions, and restrictions on investments into sensitive sectors.

Although the process of implementing competing tariffs has now largely ended, there are many residual barriers and new restrictions are being imposed. But the policy focus is moving to more positive measures. Massive amounts have been legislated (and more proposed) in the US for investment in infrastructure and innovation in the US. Priority areas include AI, big data, 5G, semiconductors, and so on.

These investments are often explicitly framed around rivalry with China. In an April speech to Congress, President Biden said that ‘We’re in competition with China and other countries to win the 21st century… We’re at a great inflection point in history.’

These are the sort of measures that China has been making for some time: Made in China, the Greater Bay Area initiatives (including Hong Kong), and so on. And Europe is focusing on strategic autonomy, which has implications for strategic investment in innovation: from semiconductors to developing leading global competitive positions in the green economy.

This innovation-heavy policy approach is familiar to smaller economies. But this big power rivalry is likely to lead to competing technology and regulatory blocs, which will require other small countries to make hard choices – from 5G networks to M&A activity. And increasingly, the US is forcing some of these choices.

There are risks of getting caught in the crossfire. This will be a more challenging phase to navigate than the trade wars, which small open economies were able to navigate reasonably well; it was the direct protagonists that incurred the highest costs.

The silver lining to geopolitical rivalry

There are costs to global economic fragmentation, the disruption of supply chains, and so on. But as in other domains, competition between countries can be a good thing – creating sharper incentives for investment and innovation.

During the Cold War of course, geopolitical competition led to greater innovation (as well as the substantial costs). The most obvious example was President Kennedy’s commitment to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade, largely motivated by the rivalry with the Soviet Union.

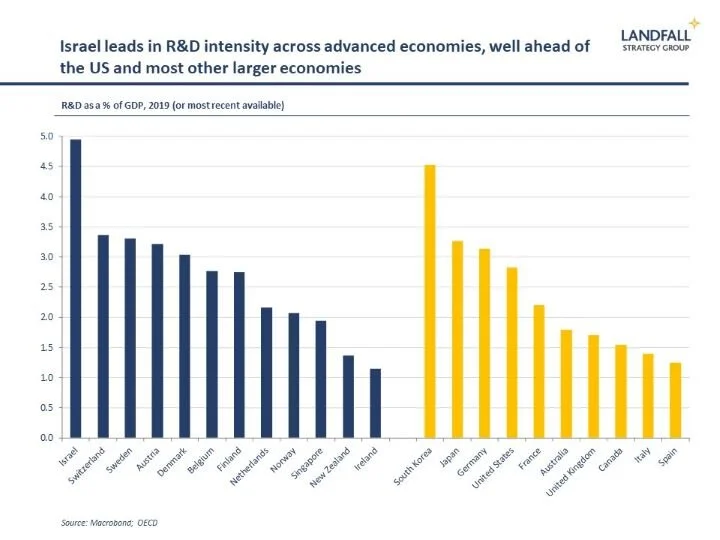

Israel is another example in which regional tensions have supported strong innovation performance, with spillovers from the defense innovation complex. Israel’s R&D spending is among the highest across advanced economies.

The shift to a more positive agenda that leads to more investment in human capital, innovation, and infrastructure can create economic upside at a national level, as well as for firms that are active in relevant sectors (although there are risks associated with aggressive industrial policy, creating national champions, and so on).

It would be nice to return to a focus on deep engagement between the major power blocs, but the reality is that geopolitical tensions will be a defining characteristic of the decades ahead. The silver lining may be more rapid innovation than would otherwise be the case.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

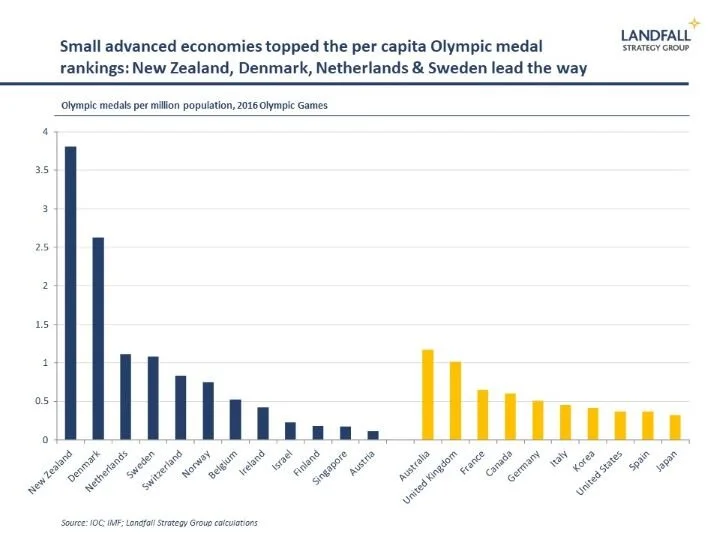

As the troubled Olympic Games start in Tokyo, keep an eye on the smaller countries to perform. On a per capita basis, small countries have historically dominated the medal rankings. In the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, New Zealand led with 3.8 medals per million population, followed by Denmark (2.6), and the Netherlands and Sweden (at 1.1). The US topped the overall model count (at 121) but lagged on a per capita basis (0.4 per million). Japan was one of weaker advanced economies on a per capita basis, so is perhaps hoping that the home advantage will help its athletes over the next few weeks.

Around the world in small economies

A good piece on the outflow of people from Hong Kong, and the implications for Hong Kong's position as a hub - including some of my thoughts on the situation.

Singapore’s advance GDP reading for Q2 reported a contraction of 2.0% for the quarter, in large measure due to the various lockdown measures that had to be imposed, but was up 14.3% since Q2 2020. The official forecast GDP growth range is 4-6% for 2021.

Also in Singapore, sovereign wealth fund Temasek reported strong growth (+25%) in the value of its portfolio to S$381 billion (~US 280 billion). It is shaping its portfolio around four trends: digitalisation, sustainable living, future of consumption and longer lifespans.

Leuven, a Belgian university town, is home to a little known but world-leading semiconductor research facility. It is of increasing interest to the US, China, and others.

Greenland is ending a 50-year ambition to produce oil, announcing that it will stop granting exploration licences for oil and gas. And Singapore is transitioning from an oil hub to a greener future (this Bloomberg piece includes come comments from me). Meanwhile, Norway’s Prime Minister has ruled out policy changes to speed up the transition away from drilling for oil and gas – arguing that there is a need for Norwegian oil and gas.

The Economist writes that Israel is being forced to make some choices between the US and China. There has been a marked slowdown in Chinese investment into Israel, partly due to US pressure on concerns about Chinese access to Israeli innovation and infrastructure.

Moves are underway to extend digital trade agreements in Asia to include the US and others. As with the TPP, this enthusiasm for innovative trade agreements across the Asia Pacific region has been driven by small countries such as New Zealand, Singapore, and Chile.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling