Unknown unknowns in a post-Covid world

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

‘… as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones’, Donald Rumsfeld, 12 February 2002.

For someone that acknowledged the widespread existence of uncertainty and ignorance about the world, former US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld – who died last week – possessed a remarkably confident, hubristic approach to decision-making. This led to the disaster that was the Iraq War.

But for all of the flaws of the messenger, Mr Rumsfeld’s observation on uncertainty contains insight. There are many situations in which we cannot describe the relevant states of the world or the associated probabilities. Or to extend economist Frank Knight’s framing, there is a difference between risk (known states and probabilities), uncertainty (known states, unknown probabilities), and ignorance (unknown states, unknown probabilities).

Indeed, Mr Rumsfeld’s observation is particularly relevant at the moment. There are many areas in which there is heightened uncertainty: the path of Covid, the extent to which economies will be structurally changed (remote working, new growth sectors, changed travel patterns), the path of inflation and interest rates, and so on (or England’s recent footballing success).

And, of course, the Covid pandemic came as a surprise – although it was more a known unknown than a black swan, with pandemics routinely included on lists of global risks. But few governments and companies were well prepared for the scale of the economic, health, and social shock.

Avoiding hubris and fatalism

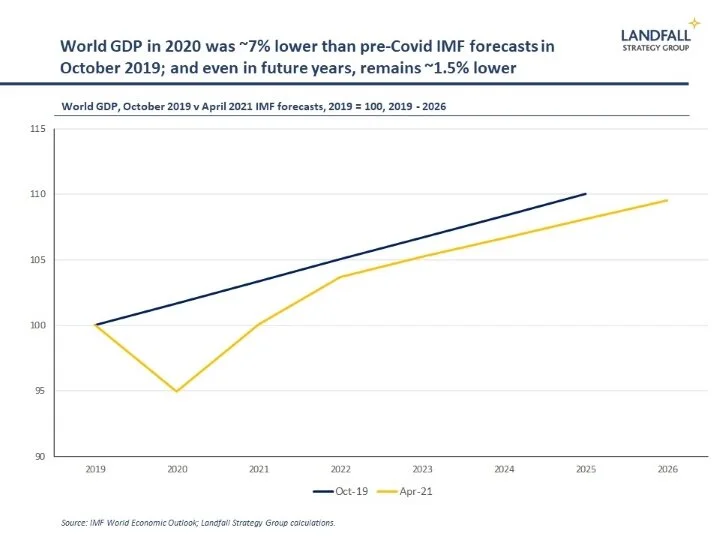

I am optimistic about the global economic outlook, broadly in line with the consensus view. But the confidence intervals around these forecasts are unusually large, with deep uncertainty about the underlying shape and nature of economic activity.

There will inevitably be positive as well as negative surprises. To name just a few, there is the potential for a tech inspired productivity renaissance as well as for climate disasters and political or geopolitical shocks.

Some intelligent guesses can be made, but in many cases we simply don’t know. We are in a world of radical uncertainty or ignorance on many important areas, with many unknown unknowns (Gillian Tett wrote a good recent FT column on the limitations of economic forecasting).

Navigating a deeply uncertain world will be a key test for institutions over the coming years. At a minimum we should proceed with humility, operating with a wide range of scenarios in mind. But deep uncertainty should not freeze decision-makers into inaction.

The inability to accurately forecast does not mean that fatalism is appropriate: governments, firms, and investors should not simply respond to events as they happen.

It is possible to act with deliberateness and strategic purpose, even while acknowledging the constraints on our understanding. As F Scott Fitzgerald noted, ‘The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function’.

Implications for action

The small advanced economy experience provides a sense of how countries can function successfully in a deeply uncertain environment. These economies have prospered while being subject to high levels of economic volatility and deeply exposed to external economic and political dynamics.

This experience is also relevant to larger economies: as deep uncertainty reaches further inside large economies, they become more similar to smaller economies.

There are five characteristics that are instructive.

First, thoughtful allocation of risk across the economy. Many small economies have strong social insurance and labour market policies. This means that people are more willing to support open, flexible policy settings because they know that the associated risks will be shared across the population. Systems that allocate substantial risk to individuals to bear can dampen incentives for taking risks. As uncertainty increases, these risk allocation choices will become even more important.

Second, a strong fiscal position so that governments can absorb and respond to shocks when they occur. Several small economies (e.g. New Zealand, Singapore) were among the most aggressive in providing discretionary fiscal stimulus in 2020, supported by their strong fiscal starting position. Indeed, the high level of economic risk exposure is a key motivation for small economy fiscal discipline. Government balance sheet management will be a priority in a turbulent economic environment.

Third, deliberate investment in areas that will position them to prosper in the future. It may not be possible to forecast which specific skills or industries will prosper, but a strong base of human capital and innovation capability supports countries to move quickly into new areas. Strategic investment in skills and innovation provides real options for countries; whereas adopting a ‘wait and see’ approach to investment can reduce the available options.

Fourth, government institutions that support agility and responsiveness – an ability to respond quickly to changing circumstances. The quality and speed of the response to Covid was strongly related to the strength of state capability. Inertia is costly.

And lastly, despite deep uncertainty, structured thinking about the future is valuable. From Singapore to Finland, many small economies invest heavily in understanding how the world is changing, looking for early warning signals, building scenarios – and are less likely to be surprised as a consequence. A short-term, reactive orientation is dangerous.

Countries - and private sector institutions - that have these characteristics are likely to perform relatively well in a deeply uncertain world.

Looking forward

Despite Mr Rumsfeld’s insights, he heavily over-weighted the extent of his knowledge – and under-played the extent of the unknown. As we move into a deeply uncertain environment, governments, firms, and investors will need to adapt their existing approaches to manage their exposure to deep uncertainty.

Using the same rules and playbook in this different context will likely lead to economic and political costs. Innovation is required to prepare for future unknowns.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

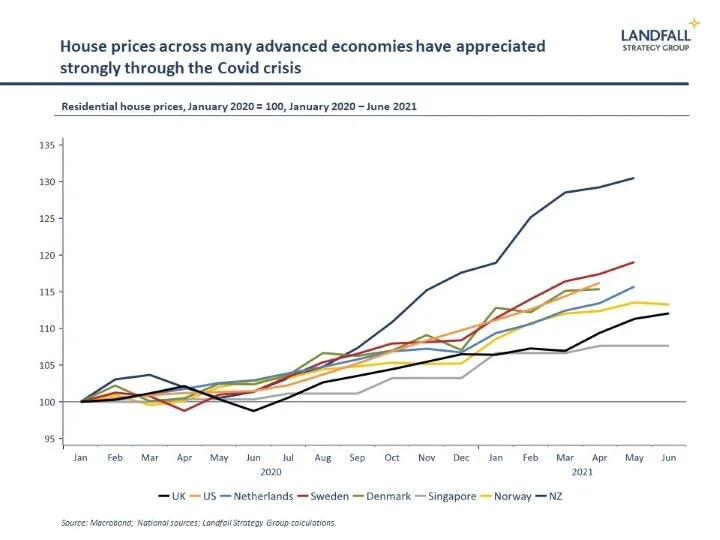

House prices have surged over the past 18 months, counter to expectations at the start of Covid. This is widespread across advanced economies, but many small economies have seen particularly strong house price appreciation: New Zealand is up 31% since January 2020, Sweden by 19%, and the Netherlands by 16%. US and UK house prices are up by 16% and 12% respectively. The wealth effect has been positive for the recovery, but it has further reinforced deep patterns of wealth inequality and worsened housing affordability.

Other writing

A paper I prepared on challenges and opportunities for Hong Kong of deeper economic integration into the Greater Bay Area, drawing on the integration experiences of other small economies, was published by the Hog Kong University of Science & Technology. It is available here.

And I was quoted in this good Bloomberg piece on the messy and long Covid end game.

Around the world in small economies

Singapore is preparing for broader opening up over the next few months as vaccination rates increase, moving to a situation in which it can live with Covid in endemic form. Meanwhile Israel, which has led on vaccinations, reports that vaccines are less effective against delta than earlier variants (although still offering strong protection against more severe cases). It is reintroducing requirements around mask wearing.

The New Zealand Treasury has commenced a Macroeconomic Framework Review to understand what structural changes in the economic environment mean for its approach to macroeconomic management.

Small economies are at the core of the semiconductor industry. This is a good piece on Dutch company ASML, the ‘the most important company you never heard of’. Valued at just under $300b, it makes machines that make the world’s most advanced chips.

The Israeli foreign minister visited the UAE for the first time on the back of last year’s agreement to normalise diplomatic relationships. Multiple business deals have also been signed since the agreement.

An amusing Economist article describes Belgium as ‘the world’s most successful failed state’. Although I note that Belgium has organised one of Europe’s most effective vaccination programmes, with per capita vaccination rates of >100%, so it does some things very well.

About 30 Danish media companies are forming a collective to negotiate with Google and Facebook for payment for news content, so that the tech giants cannot ‘divide and conquer’.

An experiment across ~1% of Iceland’s workforce found that reducing weekly working hours from 40 to 35 (on the same pay) led to no reduction in productivity or service levels but higher levels of wellbeing. I regret to advise that this has not worked for me…

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling