Two cheers for the G7

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The recent G7 meetings in the UK followed by NATO and EU/US meetings in Brussels provide some evidence that the West is back. This is supported by the return to the table of the US: President Biden left the G7 without ripping up the communique.

Although substantive differences remain (notably between the EU and the US, as well as on the implementation of Brexit), there is a willingness and ability to work together. The tone is markedly different from recent G7 meetings, when President Trump made consensus near impossible.

This provides some sense of a more confident, aligned group of developed countries as the strategic competition with China continues. And there is a renewed commitment to strengthening multilateral institutions, and working together on global issues, even if few concrete announcements came out of these meetings.

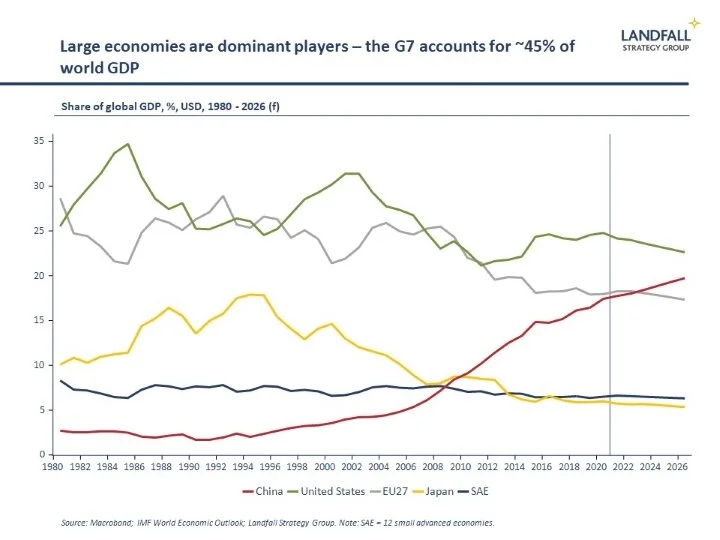

This matters because progress on global issues, from climate change to distributing vaccines, cannot be achieved without committed large economy leadership. The G7 accounts for ~45% of global GDP; and the G20 is ~90% of global GDP.

The risks of policy universalism

The renewed G7 coherence and willingness to work together on multilateral issues is positive for delivering better global outcomes. At face value, this is positive also for small economies given their deep exposures to the global system.

However, a more structured large country grouping is not an unmitigated blessing for small open economies. Large country preferences do not map perfectly onto those of small economies – and nor are they always right.

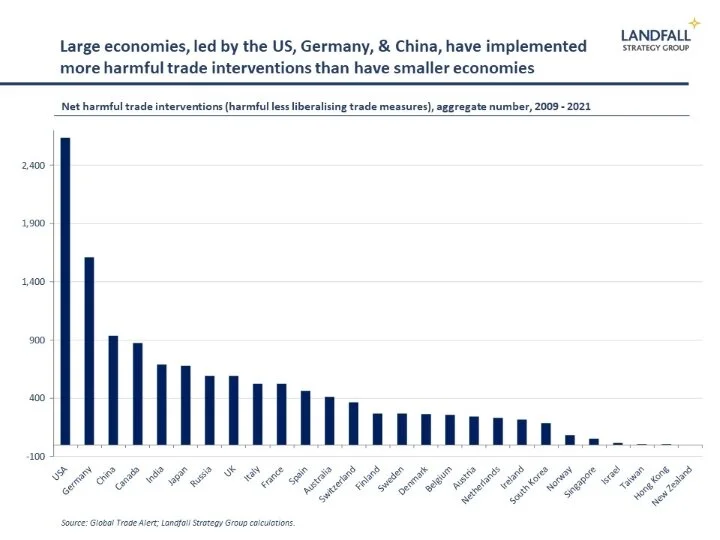

For example, large countries are increasingly imposing protectionist measures (tariffs, sanctions, supply chain constraints) which restrict globalisation. The Global Trade Alert reports that G7 and G20 members are the worst culprits by a margin in implementing trade restrictions.

And despite some recent progress in the EU/US trade relationship (e.g. plans to remove steel tariffs, and to work together on issues such as semiconductor supply) it is concerning that many of the Trump Administration’s trade restrictions remain in place - as well as its policy not to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

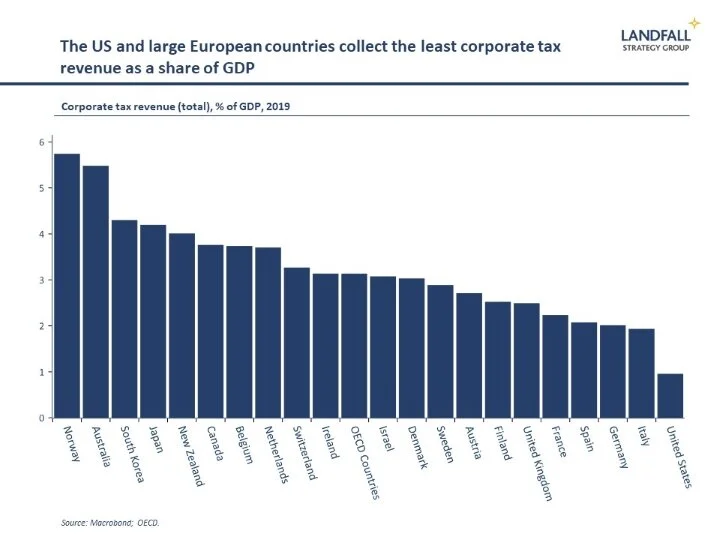

Beyond this, there is a risk of G7 policy universalism in which large economy policy approaches are imposed on others. The US-inspired G7 agreement on global minimum corporate tax rate is one example.

There is clearly a need for sweeping global corporate tax reform to align real economic activity with the tax base, and to ensure that corporates cannot avoid tax through aggressive tax planning. The status quo is not economically, politically, or morally sustainable.

Corporate tax reform is not a straightforward issue, requiring a balance between global rules and national sovereignty to deliver good global outcomes (see this piece by Dani Rodrik). But the G7 agreement needs to command a broad consensus, including through the OECD’s successful BEPS process - which has already made substantial progress on corporate tax reform.

Imposing a minimum corporate tax rate removes a legitimate policy instrument for small economies like Ireland, Switzerland, and Singapore that has helped them to compete with larger economies. This approach to tax reform is politically easier for large economies than undertaking domestic corporate tax reform to ensure that MNCs pay appropriate tax. It is striking that large economies collect little corporate tax as a share of overall tax revenue, and as a share of GDP.

Although a 15% minimum corporate tax rate is unlikely to do significant damage to the economic models of small economies like Ireland and Singapore, the broader risk is that it sets a precedent for future large economy calls for wider fiscal policy harmonisation.

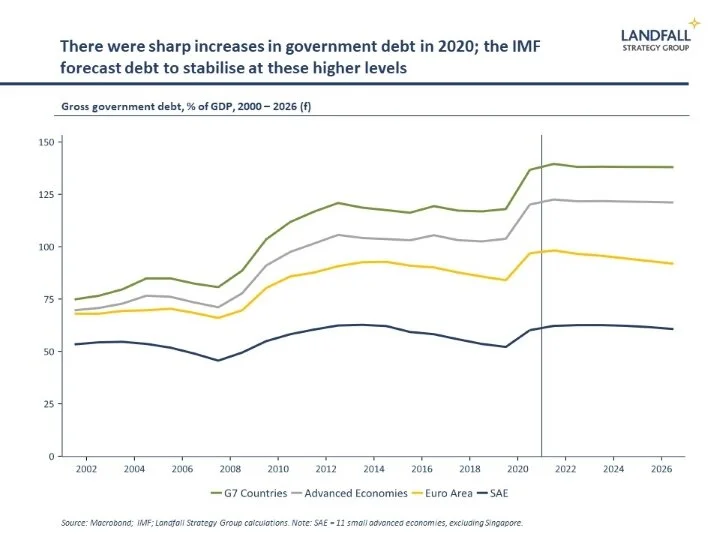

Indeed, differences are emerging on fiscal policy, where large economies are increasingly comfortable with structurally high amounts of public debt. Fiscal stimulus has been important in responding to the Covid crisis, including in small economies where several have led in terms of aggressive discretionary fiscal stimulus. But fiscal policy constraints are tighter in small than in large economies, and one size fits all fiscal policy approaches are not appropriate.

Competition matters

Large states are important underwriters of the global system, but this should not translate into large economy policy universalism.

Although large economy policy leadership and action is important, and it is unsurprising that they seek to advance their interests, these policy perspectives should be open to competition.

In particular, it is important to have a small economy perspective on economic policy debates at the G7 and elsewhere. I have previously argued for an informal ‘g20’ of high-performing small advanced economies to bring small economy policy insights into global policy discussions at the G20.

Small advanced economies are deeply exposed to the global system, generate strong economic and social outcomes, and are often in the vanguard of policy innovation (from monetary and fiscal policy to active labour market policy). Their explicit involvement would add valuable perspectives, strengthening policy contestability.

In this regard, the debate about the scale and design of the EU Recovery Fund is instructive. The Northern European ‘frugals’ attracted criticism for insisting on debating the original proposals, but the focus on conditionality and fiscal discipline has likely improved the quality and economic impact of the recovery package.

Overall, the return of the G7 to constructive policy debates is a welcome development, and a marked improvement over the policy conflict and unilateralism of the Trump Administration.

But care should be taken to manage the risks of G7 policy universalism. The G7 is a narrow form of multilateralism, and there are costs with an uncontested primacy of large state policy views. G7 policy stitch-ups may not serve the global economy well. Large economies should not assume that their policy context and preferences are universal.

Organisations like the OECD and the IMF should work to incorporate a broader set of national perspectives to supplement the loud G7 voice. Competition in policy debates, as elsewhere, is generally a good thing.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

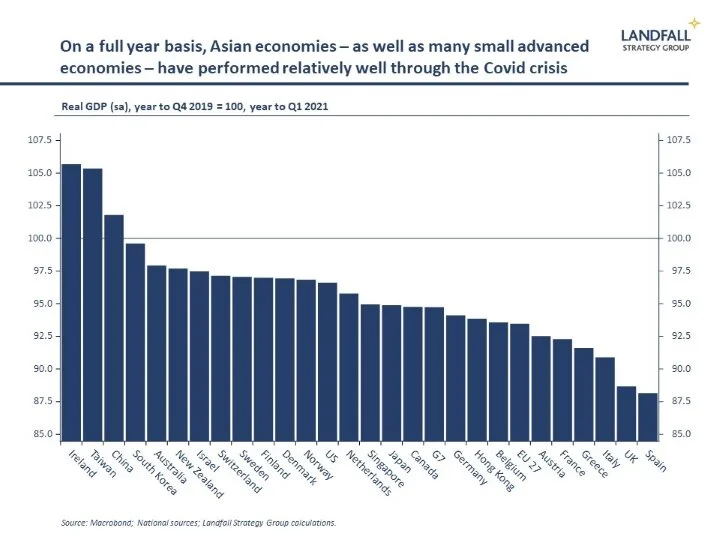

Q1 GDP data for all major economies has now been released. For the full year to Q1 GDP, GDP was generally lower than GDP for the (pre-Covid) year to Q4 2019 – exceptions include China, Taiwan, and Ireland - supported by MNC exports. Asian economies did well, with South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand also near the top of the rankings. Small advanced economies have performed well on average, with GDP down by ~3% over this period relative to over 5% for the G7. This reflects a shallower contraction in 2020, and a stronger economic recovery process across small economies.

Around the world in small economies

The European Commission’s European innovation scoreboard 2021 was released this week. Eight out of the ten top economies were small economies, led by Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Belgium.

Baillie Gifford has become one of the world’s most successful fund managers from its base in Edinburgh, with a series of high conviction bets on technology firms.

Bloomberg’s latest rankings of house price bubbles was topped by New Zealand, with Norway and Sweden also in the top 5. New Zealand experienced house price appreciation of 30% in the year to May, and several other small economies, from the Netherlands to Austria, have house price growth at multi-year highs.

Political changes (or not). A new coalition government has assumed office in Israel, replacing Prime Minister Netanyahu who had been in office for 12 years. The Swedish Prime Minister lost a vote of confidence, requiring either a new coalition or new elections. But Dutch coalition negotiations continue three months after the elections, with no near-term resolution in sight.

In a referendum last week, the Swiss rejected (by 51-49) propositions for addressing climate change (such as car fuel levies and a tax on air tickets) to meet its emissions targets. Separately, proposals are being considered to offset any financial impact of a global minimum corporate tax rate on Swiss companies.

On small economies and China. There are commercial frictions between New Zealand kiwifruit growers and China, after evidence that Chinese growers used stolen intellectual property to grow kiwifruit in China. And Lithuania has recently pulled out of the 17+1 grouping of Eastern European economies and China.

It’s been a good week for small country sporting teams. New Zealand beat India convincingly in the inaugural cricket Test Match world championships. And 10 small countries have progressed at the Euro 2021 championships: Wales continue to impress, and Denmark staged a remarkable and emotional recovery.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling