Post-Covid reset or mean reversion?

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

In many advanced economies Q2 GDP was at or above Q4 2019 levels, reflecting a strong recovery process. Looking forward, there are global economic headwinds: from delta and supply chain constraints, to slowing growth in China and the US. These concerns were reflected in markets this week. But overall, the global recovery is continuing.

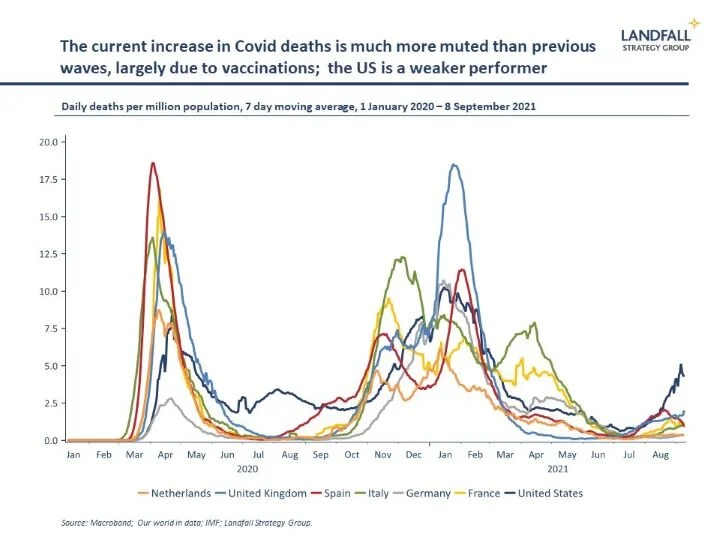

High vaccination rates in Europe and the US are allowing for a measure of normalisation. Across developed countries, the increase in Covid cases as economies have opened up has not been accompanied by proportionate increases in hospitalisations and deaths – despite the complications of delta.

It will continue to be a bumpy road, with new variants and ongoing restrictions likely. Israel, which led on vaccinations, gives a sense of what this looks like. And of course, much of the world is not in the privileged position of advanced economies in terms of access to vaccines. But things are moving in the right direction.

This time is different

But this will not be a return to pre-Covid normality. The scale and duration of this shock – ~18 months of some form of lockdown and border restrictions, with more to come – has led to a fundamental rethinking of behaviours.

Mean reversion is normally a good rule of thumb, with change often temporary. But this prolonged shock has pushed us away from this equilibrium.

An 18 month (and counting) shock is very different than a three month shock. People and firms have got used to working from home, the absence of business travel, and the use of technology (from online shopping to the use of QR codes for ordering). Once behaviours change for a sustained period of time, there is a measure of stickiness.

In politics, the ‘Overton window’ is defined as the range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream population – which can shift over time. Extending this concept, the Overton window on a range of behaviours – from government policy to consumer preferences – has shifted during Covid.

This is quite different from previous economic shocks, like the global financial crisis, which was largely a demand-side shock and did not leave a structural imprint on the economy in the way that Covid will.

A new world

Although there is deep uncertainty about the post-Covid world (with many unknown unknowns), there are some areas in which the Overton window does seem to be moving. Consider the following examples:

Macro policy

The massive macro policy stimulus in response to Covid has crystallised new thinking about fiscal policy, particularly in large economies. This makes a return to pre-Covid fiscal policy norms unlikely.

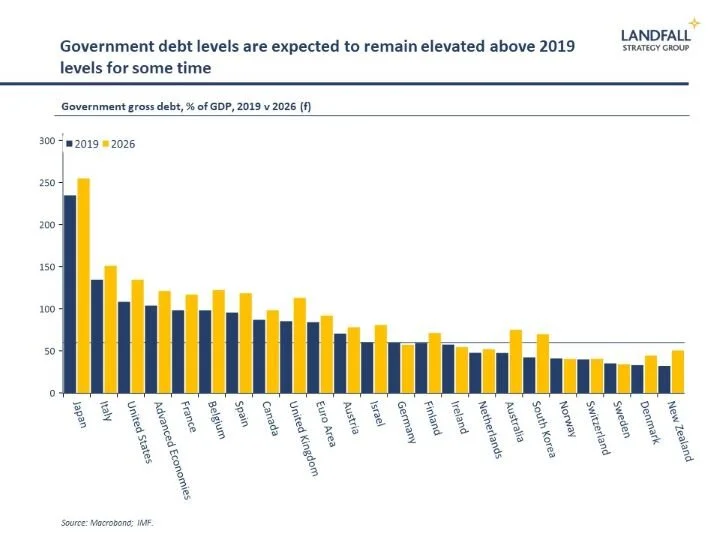

EU fiscal rules are currently suspended, for example, and will be reviewed (a return to 60% and 3% is unlikely). In the US, public debt is above 100% of GDP – and the Biden Administration is pushing multi-trillion dollar packages through Congress. The UK’s announced tax increases this week to fund NHS spending place it slightly apart, but UK government debt is likely to continue to increase.

Small economies see fiscal policy differently because of their higher risk exposures, and are less likely to move as far as larger economies.

But overall, a new macro policy regime is emerging – expansive fiscal policy, high levels of public debt, low interest rates. It will be a period of fiscal dominance, with a focus on investing in infrastructure, green and digital initiatives, and maintaining a high pressure economy. Adam Tooze captures one version of this changing zeitgeist, quoting Keynes, ‘Anything we can actually do we can afford’.

Although the centre of gravity in global fiscal policy was already moving, this regime change would likely not have happened without the emergency measures used in response to Covid.

Cross-border people flows

International trade flows have been resilient through Covid, and there is little sign of unwinding. But another important dimension of globalisation – cross border people flows – looks to be a different story.

Border restrictions have led to sharp declines in international tourism, migration, and business travel. There has been a partial recovery as vaccination passports allowed travel, but preferences have shifted. Firms around the world are committing to slash business travel, and international leisure travel is expected to be muted for several years.

China’s borders, for example, are likely to remain effectively closed for some time. And travel is likely to focus on domestic or within-region destinations, or in specific travel bubbles.

Beyond this, several governments (New Zealand, Singapore) have taken the opportunity of the hard stop in migration and tourism flows to review their policy settings – in response to concerns about the impact of over-reliance on these flows.

Structurally reduced cross-border migration flows are likely in a post-Covid world, with significant impacts likely on national economic models – from post-Brexit UK to New Zealand – and the shape of globalisation. The real world is shrinking for people, even as the virtual world expands.

Business models

Covid has accelerated the adoption of new technologies and business models. And shifting consumer preferences as well as firm learning over the past 18 months is likely to make this stick. Labour shortages, partly due to reduced migration, will reinforce this dynamic.

This is positive for the technology sector broadly defined, and has contributed to a k-shaped recovery profile – which is likely to be sustained.

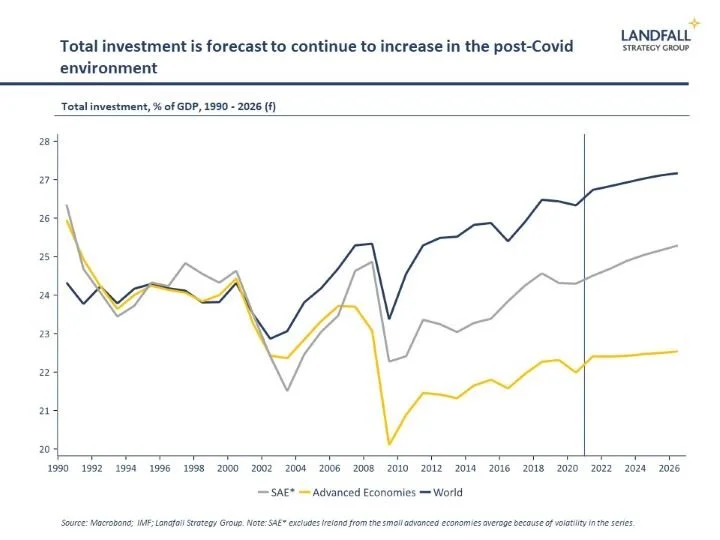

These changes have created stronger incentives for firms around capex investment – in new technologies, new machinery, and lower emissions forms of capital. Already business capex spending is recovering strongly, with more expected to come, reversing a trend in economies like the US for declining capital intensity.

The IMF forecast total investment to steadily increase as a share of GDP over the coming years. Over time, this post-Covid economic transformation will have a positive impact on productivity.

Plus ça change….…

Of course, not everything has changed during Covid. For example, climate change policy has not shifted as much around the world as is required.

And geopolitical tensions are growing, with strategic competition between the US and China continuing. There is an inward-looking flavour to many debates on global issues, from climate change to technology and trade. If anything, Covid has reinforced these dynamics.

But in many ways, Covid represents a trend break. There is a high level of fluidity in policy approaches and business models, and there is likely to be substantial change and innovation over the coming decade.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

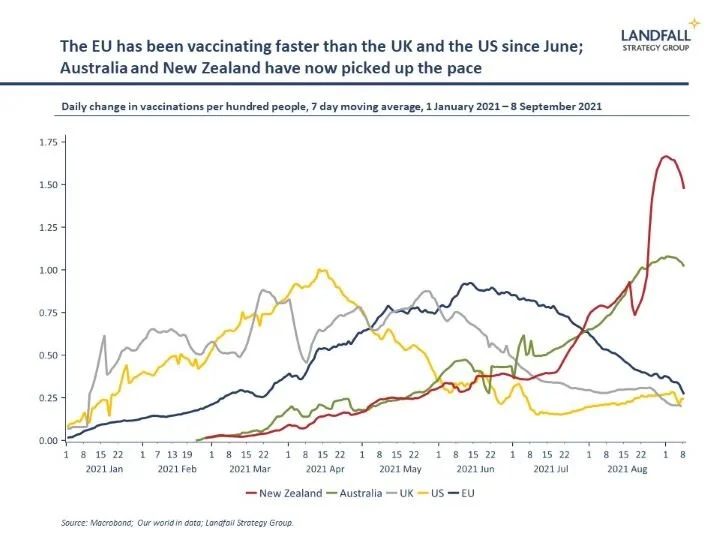

After a slow start, the EU has been vaccinating faster than the US and the UK since June – and now has higher per capita vaccination rates than the US (>70% of adults have been fully vaccinated). This is supporting opening up in the EU. Australia and New Zealand are now vaccinating very rapidly, although total vaccination levels remain low.

Other writing

I was recently on a panel at the School of Government at Victoria University of Wellington, reflecting on strategic foresight in government – and with my take on the key lessons. The video and my slides are available here.

Around the world in small economies

The UAE has recently opened up to all vaccinated tourists, as part of its recovery strategy – supported by one of the highest vaccination rates in the world. Also in the UAE, new residency guidelines have been introduced – making it easier for people to obtain permanent residency. And a new plan has been introduced to attract FDI.

It’s all happening in Amsterdam. Amsterdam’s Schiphol was the busiest airport in the world in August, overtaking Dubai, as vaccination passports and summer weather supported travel. And Amsterdam is again the top equity trading market in Europe, beating out London (again).

Fiscal conservatism in small economies: the pre-budget letter from the Governor of Ireland’s central bank to the Minister of Finance called for ‘A credible path to a lower debt ratio over the medium term is needed’. And the Swedish Minister of Finance has rejected calls for a new fiscal policy framework to allow for increased government spending.

Budget negotiations continue in Portugal on how to spend the EU Recovery Package grants and loans (it is relying more on grants and will not take the full loans on offer in order to manage its high level of public debt). The government has announced measures to tackle youth unemployment, increased child tax benefits, as well as investments in health and social security.

The Irish Government has announced guaranteed state funding of at least €4 billion a year for the next five years to finance the construction of 300,000 houses by 2030 in response to the ‘social emergency’ of the housing crisis.

Small economies are benefiting from stronger external demand. Greece registered 16% growth in the year to Q2; and tourism income will likely contribute strongly in Q3. And Taiwan’s exports are growing at >25% (and are expected to continue to perform strongly) on very strong demand for electronics.

On small state diplomacy. Qatar has emerged as a bridge between the West and the Taliban on the back of sustained diplomatic investment. However, challenges lie ahead. Elsewhere, Norway is mediating talks underway in Mexico between Venezuelan political parties.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling