Commodities, technology, & the commanding heights

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Vladimir Putin once said that whoever controlled artificial intelligence would control the world. Maybe so, but that won’t be Russia. John McCain’s description of Russia is closer to the mark: ‘It is a gas station run by a mafia that is masquerading as a country’. The direct global economic impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is largely transmitted through energy and other commodities.

Technology is commonly thought to dominate the commanding heights of the global economy, such as the tech giants of the US and China (Amazon, Google, Alibaba, and many others). And over the past two years, innovation on vaccines has been central to economic and health outcomes. More broadly, some have argued we are in an intangibles economy where assets like brands, ideas, and relationships matter more than physical capital.

Technology indexes have soared over the past few decades, and economies that have strong technology capabilities have performed well – from Silicon Valley to Israel and Taiwan. And through Covid, investment in digital and other technologies has accelerated in many advanced economies. It is plausible that this stepped up investment will support a productivity renaissance.

National economic policy is often focused on developing an edge in technology, from the US and China to small economies such as Singapore and the Netherlands. And China, the EU, and the US, are increasingly focused on strengthening strategic autonomy in leading technology sectors.

The tangible economy

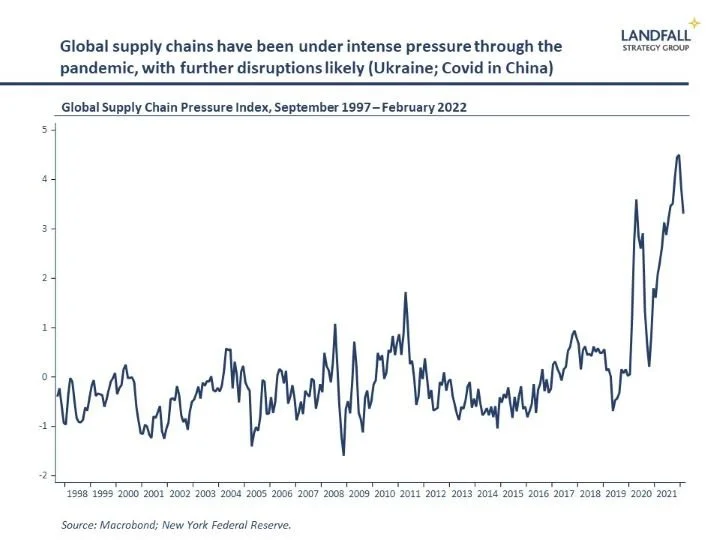

But the experience of the past two years, reinforced by the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, shows that the world has not dematerialised. Physical flows of goods and the supporting supply chains matter. High technology activities cannot function if the supporting physical supply chains don’t function: for example, this week Dutch semiconductor tech firm ASML reported major supply chain constraints on its production.

The strong global economic recovery through Covid, coupled with the rotation of consumer spending towards goods (and away from locally produced services), led to strong merchandise trade growth – and pressures on global supply chains. Shipping costs surged and there were global delays in shipping goods. And now the Covid lockdowns in China are causing further disruptions to global supply chains.

This is leading firms and countries to think much harder about supply chain resilience, from building inventories and diversifying suppliers to re/near-shoring activity.

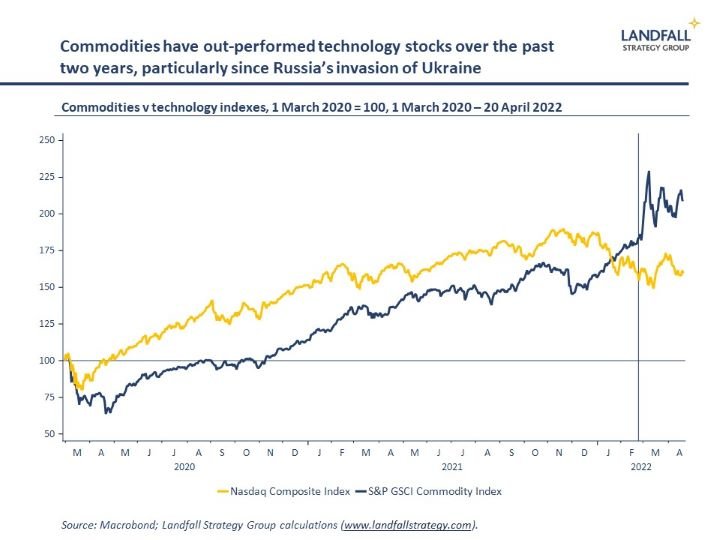

Countries and firms are also exposed to the supply and prices of energy, food, and other commodities. Global commodity prices, from energy and agriculture to industrial metals, have risen much faster than the tech-heavy Nasdaq index over the past two years – and particularly since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Oil and gas prices have increased markedly. Although advanced economies are much less energy intensive than during the oil price shocks of the 1970s, this will still cause economic pain to firms and households – as the IMF’s World Economic Outlook noted this week. Those countries that have energy independence will have an advantage; the US is advantaged relative to Europe, for example, because of its domestic energy resources.

Over time, renewable energy and green hydrogen offer the potential for greater resilience against these shocks. Many countries are ramping up plans for renewable energy production over the next decade and beyond, partly to reduce external exposures (e.g. to Russian gas) as well as to meet net zero commitments.

Geopolitics will be reshaped by these new networks of energy flows, with the centrality of oil exporters reducing as countries build out (or import) renewable energy. In turn, however, renewable energy will require access to industrial metals such as copper and lithium. Few advanced economies have direct reserves of these metals; the need to source these inputs creates some new exposures (and the prices of these industrial metals have increased sharply).

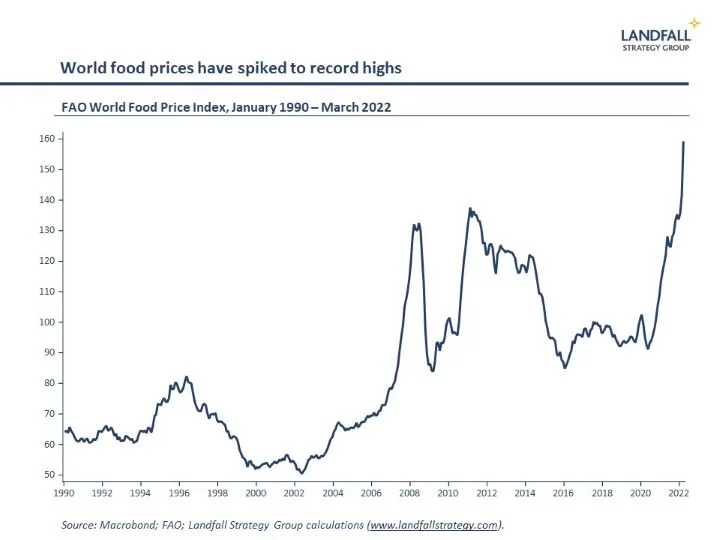

Food security has also become a big issue. Global food prices are at record highs, and are likely to sit there for some time. The lost supply of wheat and other agricultural commodities from Ukraine and Russia is already causing major disruptions, particularly in exposed markets such as Lebanon and Egypt.

High food prices are a common cause of political instability in emerging markets, as seen in Sri Lanka and elsewhere over the past few weeks. Looking forward, climate change will likely cause additional pressure on food supply: droughts/floods, reducing yields, and so on.

These higher food and energy prices have made large contributions to the surge in inflation around the world, leading to the need for higher interest rates.

The ability to secure reliable supplies of energy, food, and commodities, as well as access to well-functioning supply chains, will be an important aspect of national resilience and economic performance. Global markets have worked well for some time in supporting the efficient flows of goods and commodities. But a combination of geopolitical tensions, a fragmenting global economy, the transition to net zero, as well as commercial incentives around production, are creating structural pressures.

Let’s get physical

Those countries and firms that can combine technology/innovation leadership as well as security of supply of critical flows of commodities and goods will out-perform. And particularly when these attributes are coupled with strong institutions, a structural driver of national success.

The global economy may have important weightless properties – with more economic value coming from intangibles – but weighty matters of physical flows and commodities remain vital. Geography is not dead.

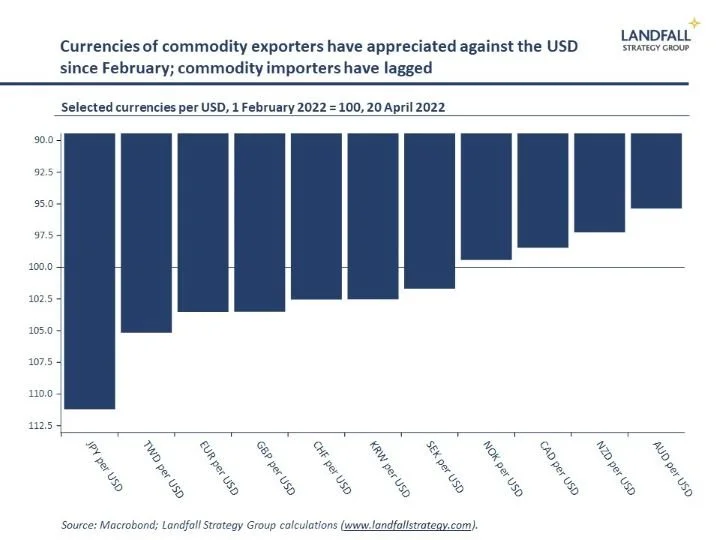

Indeed, being a commodity exporter is a good place to be at the moment. Commodity currencies (AUD, NZD, NOK, CAD) have out-performed this year against the flying USD; commodity importing currencies have lagged (JPY, KRW, TWD, euro). And from Norway to Australia (and unfortunately Russia), merchandise trade surpluses in commodity exporting countries have rocketed up over the past several months.

In an optimistic scenario, post-war Ukraine could leverage its dominant global position in a range of critical commodities, together with its technological capabilities, European integration, and strengthened institutions, to converge towards European per capita incomes.

But although commodities are not a sunset industry, countries and firms cannot rely on raw commodities alone. Massive disruption is occurring: renewable energy will displace oil and gas over time, and new technologies (vertical farming, plant-based foods, and precision fermentation) will disrupt food production. Innovation is also likely to alter demand for industrial metals (for example, around batteries). Commodity exporters should not be complacent. Firms and countries need to be active around the intersection of technology and commodities.

As is often the case, small advanced economies are leading on this because of their acute external exposures. Singapore, for example, is investing heavily in food innovation to bolster self-sufficiency (including regulatory approval for lab-grown foods), is exploring options for nuclear energy as well as importing solar energy from Australia, is a world leader in water (desalination, recycled water), and is working to strengthen its supply chains.

Countries have not paid full attention to their exposures to the physical world over the past few decades, partly because of the relatively benign global environment. But this is changing. Even leading advanced economies will need to ensure resilient supply chains, security of supply for key commodities, and invest in innovation around food, water, and energy, in order to secure a position on the commanding heights.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

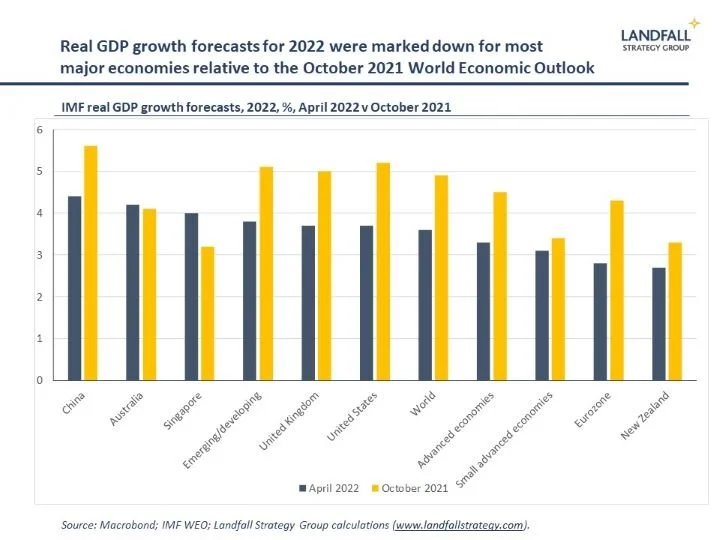

Chart of the week

The IMF released its latest World Economic Outlook on Tuesday, with a marked deceleration in the forecast strength of the global recovery compared to their October 2021 forecasts. World GDP growth in 2022 is now forecast to be 3.6% compared to 4.9% in October; and across advanced economies it is 3.3% versus a forecast of 4.5% in October. The US, China, and the Eurozone have been marked down for a variety of reasons, including the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling