Sanctions & values-based globalisation

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The horrifying pictures out of Ukraine this week of war crimes committed by Russian forces have intensified calls for tougher economic sanctions to be imposed, from oil and gas bans to a complete removal of Russian banks from SWIFT. Moral outrage is intersecting with economic decision-making.

Previous notes have argued that the Russian invasion and the accompanying sanctions will accelerate global economic fragmentation. The behaviours of Western-aligned governments and firms over the past several weeks show that there is a strong political values motivation to these dynamics, as ties with Russia are cut in response to breaches of international law.

Sanctions as symbols

Relative to initial expectations, the economic sanctions imposed on Russia have been strong and broad-ranging – although ongoing exports of oil and gas to Europe remain a large hole.

There are a few motivations for imposing sanctions on Russia: to drive Mr Putin to the negotiating table by imposing economic costs; to impose punishment and to signal condemnation of Russia’s actions; and to credibly show to future aggressors that economic sanctions will be imposed if international law or other norms are breached.

The economic sanctions are unlikely to meaningfully change Mr Putin’s decision-making (particularly when they exclude oil and gas exports). Perhaps over the next months, sanctions will constrain options and stop Russia’s war machine from working. But changing the near-term balance on the battlefield requires military support more than economic sanctions.

Indeed, economic sanctions have a very mixed history in delivering results (see this piece by Nicholas Mulder, author of a very good recent book on economic sanctions).

Instead, the core motivation for economic sanctions seems to be a combination of punishment of Russia for its barbarism and breaches of international law, as well as to strengthen the credibility of threats to use economic sanctions in the future.

The message is that Russia’s brazen breach of the rules-based system will result in its ejection from the global economic and financial system, even if it does not immediately shape Russia’s near-term behaviour. Indeed, it is not clear what conditions need to be met for these sanctions to be lifted; it is very unlikely that sanctions will be relaxed without fundamental political change in Russia.

So although they impose substantial economic costs on Russia, the sanctions are symbolic as much as instrumental in nature.

And of course, national interests still matter. Many European countries remain frustratingly wary of the higher energy costs that would come from further sanctions. But countries have been more willing to impose and absorb economic costs than was expected prior to the invasion.

From economic engagement to competition

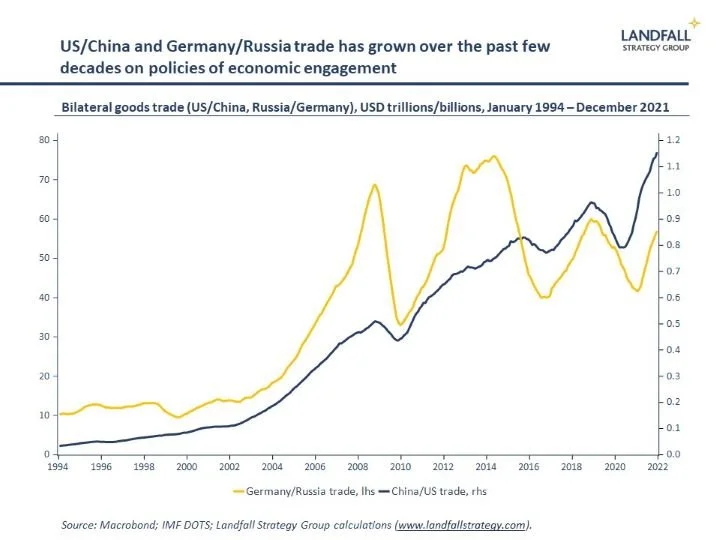

The Western-led sanctions on Russia also reflects a reversal of the belief that economic engagement will lead to convergence in political systems and behaviours. Germany has discovered the limits to the benefits of economic engagement with Russia (epitomised by Nord Stream 2), as has the US with respect to its China engagement policy over the past few decades.

Neither engagement approach led to meaningful rapprochement. Instead, there are now elevated levels of conflict and strategic rivalry. Indeed, some political voices argue that this engagement approach strengthened strategic competitors. Germany has admitted it was naïve, and the German President recently apologised for ignoring the warnings of countries who criticised Germany’s Russia policy. In Washington, a hawkish economic stance on China is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement.

There is a shift underway to a more hard-headed approach. Whereas Western governments previously tried to use economic engagement to shape political values in its economic partners, differences in political values are now shaping economic flows as Western countries increasingly engage with countries that conform to the rules-based system.

The experience of the past several weeks suggests that minimum adherence to the rules-based system (notably respecting territorial integrity) is now needed in order to fully participate in the Western-led global economic and financial system.

This greater focus on rules and values does not imply Western values universalism where every trading partner needs to be a liberal democracy. Indeed, there are plenty of flawed democracies in the West; and the West does not have clean hands after Iraq, Afghanistan, and its tepid response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine. But a brutal invasion by a UNSC/G20 member is treated as a red line.

In any case, Western views on human rights are far from universally held. Yesterday’s UNGA vote to remove Russia from the Human Rights Council was passed, but with 24 votes against and 58 abstentions (including Singapore, which has sanctioned Russia for breaching international law).

Stakeholder pressure

The increasing importance of values can also be seen in corporate behaviour. Over 600 largely Western multinationals have now withdrawn from Russia. If anything, companies have been more forceful than governments in imposing costs on Russia.

There are several reasons for exiting the Russian market: the impact of official sanctions; supply chain disruptions that constrained Russian operations; stakeholder pressure; and, for some, taking a principled stance.

For many firms, stakeholder pressure has been the dominant contributor to the decision to exit. The barbaric Russian invasion – reinforced by Ukrainian success in the information wars – has created an environment in which firms have been under huge pressure from staff, customers, and public opinion to exit Russia. Firms, such as Nestle, that tried to justify an ongoing presence have been punished.

‘We found ourselves thrust into global politics like no other moment in recent history’, Mark Schneider, Nestle CEO

For many firms, exiting Russia was a painful but relatively straightforward choice to make – it accounted for a small proportion of earnings. But to the extent that geopolitical relations worsen between China and the West, and stakeholder concerns about issues such as human rights and Taiwan rise, stakeholder pressure may make a China presence more problematic for Western firms.

At a company level, the extent of decoupling from China is partly driven by economic logic – reducing exposures to geopolitical risk and building supply chain resilience, offset by the large market and competitive advantages available in China. But values-based stakeholder pressure adds another dimension to this decision-making.

Indeed, some firms are already struggling to satisfy stakeholders in both China and their home market. These pressures will likely strengthen.

Looking forward

The experience of the past several weeks shows that economic and commercial relations are not a values-free domain. Breaches of international law have been met with aggressive responses from governments and firms. These behaviours will shape the future of globalisation.

Some of the economic decoupling underway is due to strategic competition between big powers as they grapple for dominance in areas from technology to finance. This will be reinforced by values-based behaviours by governments and firms, as countries that breach international law and norms are sanctioned. The blocs that form in the global economic system are likely to be organised around shared values as well as common strategic interests.

There will be practical limits to this values-driven decoupling. It is much less costly to aggressively sanction Russia than it is China, a large and central part of the global system. But expect differences of political values to become an important driver of global flows, as governments and firms respond to citizen and stakeholder pressure.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

We provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

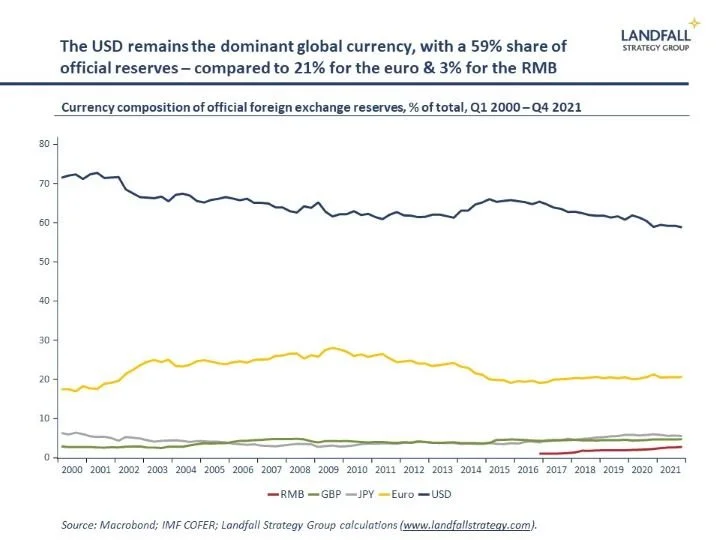

For all of the talk of risks to the USD as the global reserve currency, it remains the world’s dominant currency. 59% of official reserves are held in USD, down by ~10% over the past 20 years, with the euro at 21%. The RMB accounts for just 3% of official reserves, increasing only gradually. Some diversification into other currencies is probably underway (AUD, SEK), but this is happening on the margin. And about 90% of daily forex trades involve the USD according to BIS data. Despite financial sanctions, there is no near-term alternative to the USD.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling