Doomed to choose

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

‘We are doomed to choose and every choice may entail an irreparable loss’, Isaiah Berlin

Around the world, countries are making choices in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. From Europe and North America to the Asia Pacific, a broad group of countries have condemned Russia’s invasion as a breach of international law and imposed aggressive economic sanctions (‘the first world economic war’).

Russia’s invasion has crystallised the various challenges to the rules-based system, leading to fundamental changes in national positioning. The German government, for example, is signalling a reversal of decades of foreign policy and energy strategy – admitting to naivete on Russia, and committing to strengthen energy independence and increase military spending (although delivering on this will be very demanding).

The response to the invasion has also revealed the countries that are not aligning with the West. In the UN vote to condemn Russia’s invasion, China and India abstained, as well as multiple states in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia – together accounting for more than half of the world’s population.

The events of the past month represent a rupture in the global system, accelerating global fragmentation. Countries will increasingly coalesce around poles in the global system. It is likely that there will be a process of tightening up around ‘Western-aligned’ countries, a more pronounced decoupling of China (and Russia), as well as states trying to balance between the West and China (and Russia). Choices are being forced.

Small states as canaries in the mine

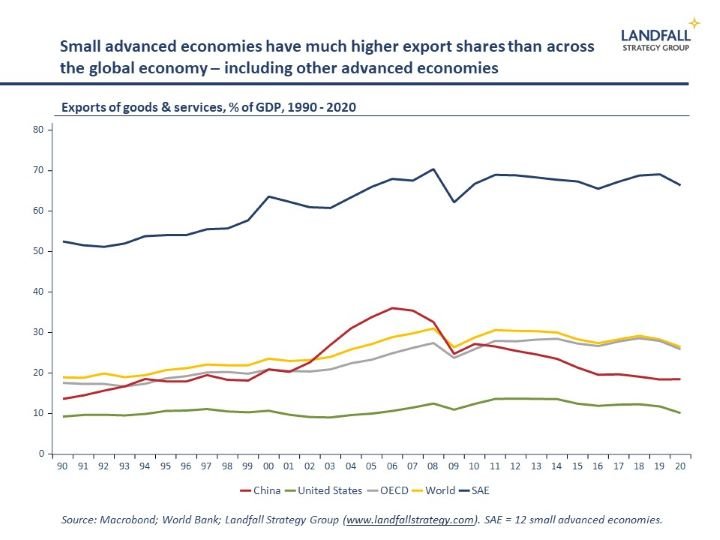

Small advanced economies are a useful place to look for guidance on these dynamics: the canaries in the mine of the global system, because of their deep external economic exposures and vulnerabilities to large power dominance.

The deep engagement of small advanced economies in the global economy creates exposures to external shocks, including the economic impact of the Russian invasion. Small economies can also be more readily squeezed by larger powers – and from Taiwan to the Baltics, there is an increasing frequency of these episodes.

These vulnerabilities mean that small states think very hard about their external positioning and global developments. In Europe, for example, it is the Baltics and Nordics that have had a sharp sense of the threat that Russia poses and the need to respond with economic, political, and security measures: Europe is belatedly converging to their perspectives. In Asia, Singapore invests heavily to understand global dynamics.

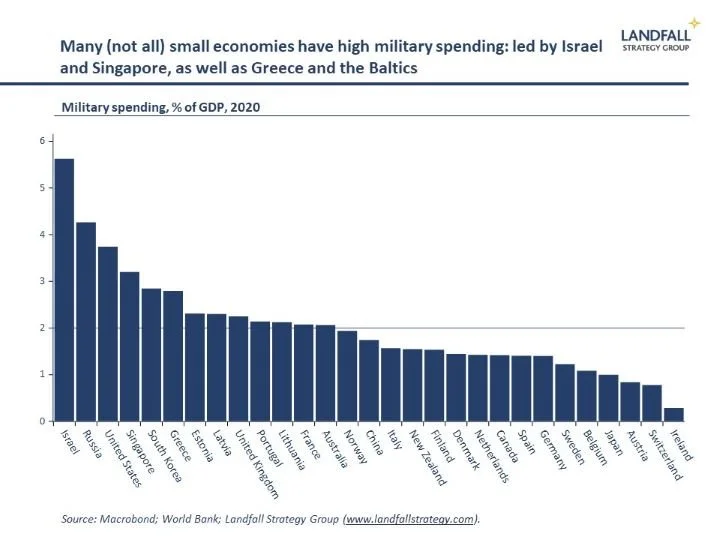

These features are one reason that many (not all) small advanced economies have high levels of military spending, notably Israel and Singapore. And several have raised military spending over the past few years, as geopolitical uncertainties have increased.

Because of these acute exposures – and the mindset that this creates – small advanced economies provide a useful perspective on international developments. Consider the following examples of change since the Russian invasion a month ago.

In Sweden and Finland, formal NATO membership is now firmly back on the agenda – with public majorities in favour in both countries, and political leadership (notably in Finland) moving in this direction. In Switzerland, neutrality has been set aside to allow for economic sanctions to be imposed on Russia - although this remains work in progress.

In New Zealand and Ireland, countries that share similar sensibilities and policy approaches, parallel debates are underway. Both have used geographic peripherality as a hedge against membership of formal alliances: Ireland has a tradition of military neutrality and is not a NATO member; and New Zealand unilaterally broke with ANZUS in the 1980s and prides itself on an independent foreign policy.

But New Zealand has just passed legislation allowing it to impose economic sanctions on Russia; and Ireland is actively debating the sustainability of its current stance. Over time, both are increasingly likely to make choices that move their policy approaches closer to their respective neighbours. This is complicated for New Zealand by its substantial economic relationship with China. As I noted last week, a fragmenting global economy is likely to require hard choices to be made with respect to exposures to China.

Elsewhere in Asia, Singapore has come out very strongly against the Russian invasion, both in words (a powerful UN speech) as well as in tough economic sanctions. Singapore views the integrity of the rules-based economic and political system as an existential issue, and has taken a stance that is distinctive relative to its ASEAN peers. Although Singapore also values ongoing economic and political engagement with China, it wants a rules-based system that protects small states.

But small states in the Middle East have been much more cautious. The UAE abstained in the UNSC vote on Russia, and Israel has not imposed economic sanctions on Russia. This is partly because of various economic and security exposures to Russia; and also because Israel has been very involved in the Russia/Ukraine negotiations.

End of the golden weather

I take a few overall observations from this recent small advanced economy experience.

First, there is a broadly-shared sense that the global system on which small advanced economies rely is facing deep threats: the Russian invasion and the Western-led response is less a discrete shock as much as a sign of regime change. This is galvanising a strategic response that would otherwise have happened more gradually.

Second, for small economies, there is an increasing awareness of safety in numbers. In Europe, the options are relatively straightforward; engagement through the EU and NATO. In Asia, it is more complex, involving the need to develop economic and security relationships with a range of larger partners. The broad direction of travel across Western-aligned small states is towards tighter relationships. In a more confronting geopolitical context, the benefits of autonomy and flexibility are increasingly outweighed by the benefits of deeper relationships.

Third, the more obvious fragmentation of the global economy along political lines is leading small advanced economies to more seriously consider managing political risks in export markets and supply chains. Responding to the integration of international commerce and geopolitics is an issue across advanced economies (strategic autonomy is a preoccupation in larger economies) but the size of external sectors in small advanced economies makes this a core strategic issue.

When advising governments on economic strategy, I often note that small advanced economies are ‘doomed to choose’: small economies cannot be competitive in everything, and need to make choices on areas of strategic focus in order to generate good outcomes.

‘The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do’, Michael Porter

And so it is here. Keeping options open by ‘balancing’ in response to these geopolitical dynamics may create more risk exposures for small advanced economies than it reduces.

For Western-aligned small states, a passive response will not support the rules-based system, will likely contribute to the accumulation of larger economic exposures, will likely worsen relations with other larger Western-aligned countries (who will be demanding more from small states), and may not buy much with countries that are challenging the system. Indeed, trying to balance may mean the worst of all worlds.

A 1990s-esque world, with the extension of the rules-based order and trade liberalisation, aggressive integration of China and other emerging markets into the global economy, and intense globalisation, was an ideal environment for small states. Strategic political choices with hard trade-offs were not required.

But that is not the world we are now in. Uncomfortable and costly though it is, hard strategic choices need to be made.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

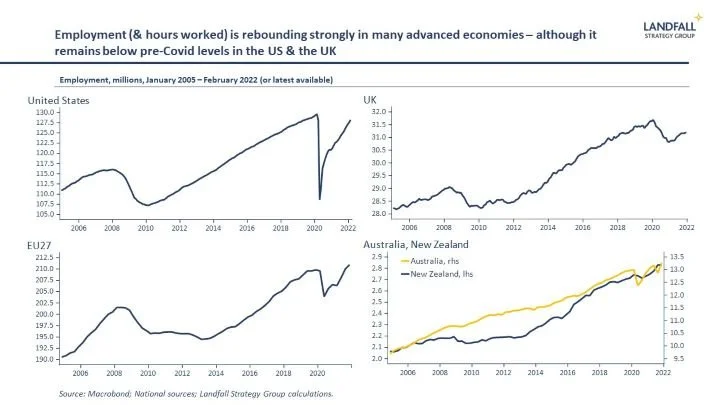

There has been a rapid recovery in employment numbers from the Covid shock. However, there is marked variation in the employment trajectory across advanced economies. In the US and the UK, employment numbers remain below their pre-Covid levels – partly on ‘the great resignation’ as people have left the workforce. However, in the EU as well as Australia and New Zealand, employment is above pre-Covid levels – partly because government support measures maintained the employment relationship between workers and firms during the pandemic.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling