The economic war reaches China

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is already a major global economic shock, in addition to the brutal military costs and humanitarian disaster. The immediate economic costs in terms of higher energy, food, and commodity prices are evident. And massive economic sanctions on Russia have been implemented.

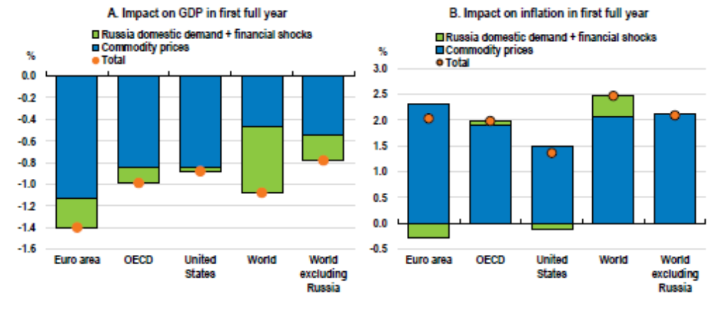

Last week, the OECD estimated that world GDP would be ~1% lower than baseline over the next year, and inflation ~2.5% higher, as a consequence of the Russian invasion and accompanying economic sanctions. The economic hit is particularly acute in Europe.

But these global economic costs – and particularly the economic costs in Asia – could escalate substantially if China gets drawn into the economic war. China was 18% of global GDP in 2021 in USD terms, the second largest in the world, whereas Russia and Ukraine combined are 2%.

This note reflects on China’s various exposures to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the likely impacts on the global economy.

A friendship with no limits?

Mr Putin met with President Xi in Beijing in February to sign a cooperation agreement, committing to a friendship with ‘no limits’.

But the unsuccessful Russian invasion, the aggressive economic sanctions (with strong backing from several Asian countries), and the economic hit to China (higher commodity prices, supply chain disruptions), is bad news for China – particularly in an important political year. Indeed, there seems to be unusually active debate in China about the wisdom of a close relationship with Russia.

China has since walked a fine line, abstaining in the initial UN votes that condemned Russia’s invasion, calling for peace, but also finding opportunities to vote with Russia more recently.

The difficulty for China is that it is caught between competing objectives: support for Russia, and a joint desire to reduce Western influence; commitment to territorial integrity and non-interference (a staple of Chinese diplomacy) that Russia has breached; and a desire to avoid economic costs and continue global economic engagement (China wants the war over, and to avoid sanctions). And personally, it is difficult for President Xi to change course.

Although China cannot walk away from Russia, it also seems unlikely that China will double down on Russia to the extent that it compromises other core interests. The US has warned China that if it provides military or financial support to Russia, or assists Russia to avoid sanctions, economic sanctions will be imposed on China.

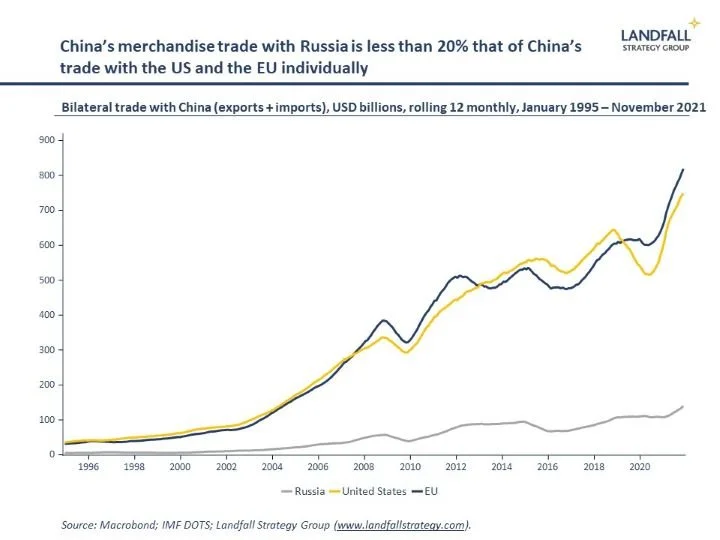

China’s economic relations with the US, the EU, and other members of the Western alliance are much larger than with Russia. So despite the rhetoric of a friendship without limits, there will be near-term limits to what China is prepared to do. Ongoing ‘pro-Russian neutrality’ is more likely.

Note also that China is likely to benefit from a weakened Russia. It will be able to drive a harder bargain on energy and commodity imports; and it is already looking for opportunities to acquire cheap Russian assets and firms. This will be an increasingly unequal relationship, with the Russian economy facing deep and enduring challenges.

A shot heard around the world

But even if China is unwilling to run the risk of sanctions because of stepped-up support for Russia, China is exposed to the emergence of a more fragmented global economy in which trade and investment flows are shaped by political fault lines. And the Russian invasion of Ukraine has accelerated this fragmentation process.

Decoupling between the US and China has been underway for some time, with increasing restrictions on trade and investment flows. These restrictions will strengthen, particularly in strategic sectors such as technology. Attitudes in Europe towards China are also hardening (albeit from a fairly soft base), with various restrictions imposed on trade and investment with China in sensitive sectors.

Russia’s invasion has further sharpened this sense of strategic rivalry with countries that are challenging the current rules-based system, notably China. And a precedent has been created for the use of sweeping economic sanctions against a G20 country. This makes it more likely that sanctions will be used in the event of significant political disputes with China, such as Taiwan.

The caveat is that differences in national exposures to China may make it more challenging to assemble the same broad-based coalition that came together against Russia (the EU has much greater exposures to China than the US, for example). And the economic scale of China likely means that any sanctions would be less sweeping than those imposed on Russia.

But overall, developments in the global system over the past few weeks create heightened economic risks for China.

This potential for sanctions makes it more likely that China will accelerate its domestic turn (‘dual circulation’), and its decoupling from Western economies, in order to reduce its external risk exposures. As with Russia’s ongoing oil and as exports, this decoupling will not be complete. But there is now an increased risk of a meaningful reduction in intensity of economic engagement with China.

Managing exposures

Although China is not the focus of the economic war on Russia, the sharpening strategic rivalry and the precedent of sanctions increase the odds of further economic conflict between China and the US, Europe, and others. This increased potential for economic conflict with China broadens the set of countries and firms that are materially exposed to changes in the functioning of the global economy.

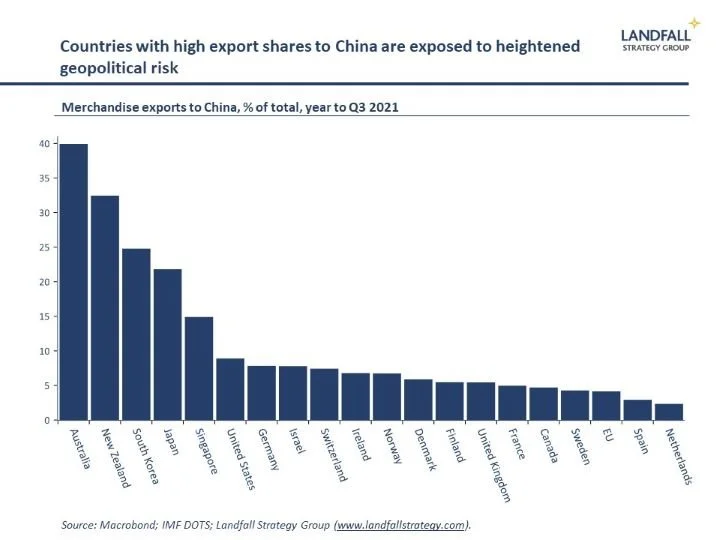

Although the direct economic exposure of Asian economies to the Russian invasion is more limited than for European economies, these economies are deeply exposed to structural global changes that impact on China. Indeed, many advanced economies that imposed sanctions on Russia (Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea) have significant economic exposures to China.

To the extent that geopolitical tensions with China rise over time, these economies will need to respond. For example, ensuring appropriate market (and supply chain) diversification to manage China-related geopolitical and economic risk exposures. This will take time, and likely involve some costs. But a failure to diversify exposures can also be costly, as European countries that are reliant on Russian oil and gas have experienced.

And the risk profile for multinational firms that do business in China has increased because of the higher likelihood of sanctions being imposed in response to political disputes (either by Western governments or by China). The past month has reinforced that geopolitics and commercial relationships cannot be cleanly separated. Indeed, many Western firms have been quick to cut ties with Russia because of sanctions, stakeholder pressure, or supply chain disruptions.

As geopolitical risks and stakeholder pressures increase for many multinational firms active in China, they should be thoughtful about deliberately managing exposures. Otherwise, they may need to respond under duress in a crisis situation. And whereas income from Russia operations was relatively small for many multinationals, China’s commercial materiality is utterly different.

A structural break in the global system has occurred over the past month, and countries and firms around the world need to respond. There is no going back to pre-invasion ‘normality’.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Feel free to get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

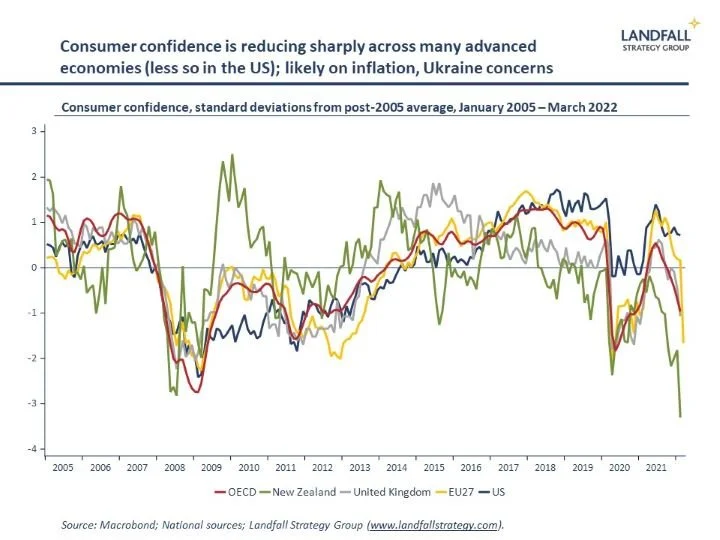

Consumer confidence has reduced sharply across many advanced economies (although less so in the US) over the past few months. Sharp falls have been seen in the EU and New Zealand, and declines have also been registered across the OECD as a whole. There are likely several contributing factors: the impact of inflation and higher interest rates on household budgets, the lingering effects of Covid, and general concerns about the effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling