The return of the 1970s?

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

‘History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes’, Mark Twain

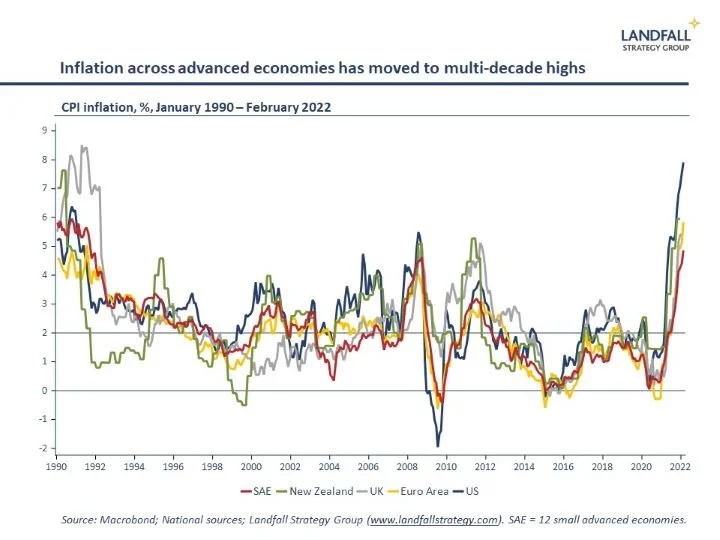

Inflation is at multi-decade highs, energy and commodity prices have moved sharply higher, there is weakening economic activity from Europe to China, as well as geopolitical conflict and tensions, and a fragmenting global economy.

Three decades on from the post-Cold War settlement, the global economy is entering a new regime.

There are parallels to the 1970s. Inflation rose sharply in many advanced economies from the early 1970s, partly in response to expansionary macro policy. And the oil price shocks that came after the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the 1979 Iranian Revolution created price pressures as well as a major economic hit across advanced economies.

International economic and financial turbulence increased after the US unilaterally exited the Bretton Woods system in 1971 and the world moved bumpily to a floating exchange rate system. And the 1970s saw widespread domestic and international political tension and volatility.

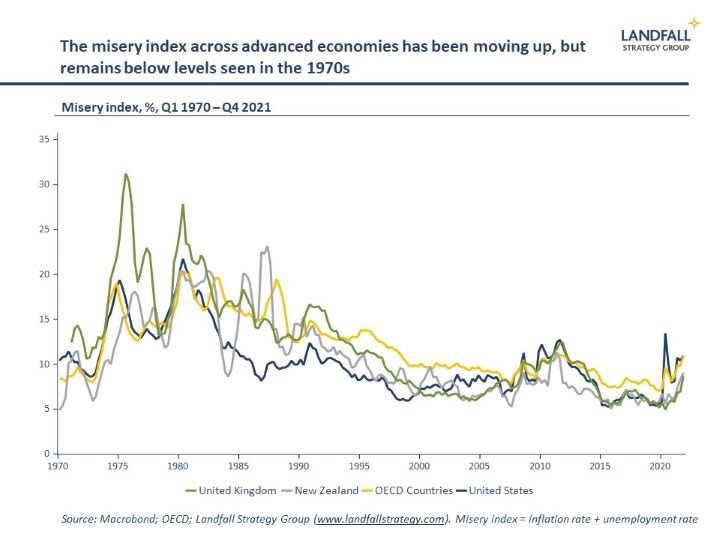

Of course, the analogy is imperfect. Advanced economies are performing better than in the 1970s, with much lower ‘misery index’ scores (inflation rate plus employment rate).

Stagflation is a risk, but it is not my baseline: institutions and policies (central banks, wage bargaining practices) have changed across advanced economies, which constrain inflation risks; advanced economies are much less energy intensive; and the underlying economic outlook looks better.

However, the combination of expansionary macro policy (including recent pressures for increased government spending), global supply chain disruptions, decoupling and growing frictions on globalisation (the ‘first world economic war’), as well as higher energy and commodity prices, is likely to create economic conditions that have some similarities to the 1970s.

Economic regime change

But there is a deeper analogy to be drawn to the 1970s beyond higher inflation, energy price shocks, and economic volatility. The 1970s was also a period of economic regime change. The Keynesian economic policy consensus was unravelling, having been pushed to breaking point; the international financial system was changing structurally; and global supply chains were being re-oriented, particularly around energy.

The observed economic shocks, such as stagflation, were largely a function of shifts in this underlying global economic regime.

And so it is now. Consider a few examples. After decades of intense globalisation, a more fragmented global economy is emerging, where global flows are shaped by political forces and where there is a shortening of supply chains. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, together with the accompanying sanctions, has crystallised these changes, and will accelerate a structural reordering of the global economic system.

Covid has also caused major supply-side shocks to the economy, beyond the immediate economic disruption. It accelerated various trends, such as the adoption of new technologies and business models (digital, automation); and seems to have altered labour force participation rates. Covid has also changed the structural growth profile of different sectors, requiring substantial flows of labour and capital across the economy to respond to changing demand.

Energy, industrial, and transport systems are beginning to undergo transformational change to reduce emissions intensity in line with net zero targets as well as changing stakeholder preferences. This will likely be a disruptive process.

And the macro policy consensus has been shifting. There is greater comfort with higher levels of public debt; as well as an emerging tendency towards ‘fiscal dominance’ in which monetary policy is subordinated to fiscal policy.

These significant, intersecting changes that are occurring simultaneously across multiple areas will create new challenges. For example, many of the current inflation pressures are due to the strong global recovery hitting up against various supply-side constraints: global supply chain disruptions; labour supply shortages in high-growth parts of the economy; the rotation of demand towards consumer durables during Covid; as well as higher energy and commodity prices as demand and supply patterns change.

Periods of regime change will likely lead to higher levels of economic volatility, as in the 1970s. At a minimum, we should expect higher inflation than over the past few decades, reconfiguration of global flows, and substantial challenges to labour markets, reinforced by disruptive changes to economic policy across advanced economies.

Policy responses

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’, George Santayana

The 1970s experience shows that new approaches are required to navigate this world. A key reason for poor outcomes through the 1970s was the policy response, which emphasised demand-side policies and protectionist measures. Policy was designed to offset external shocks rather than to position for a structurally changed world.

New Zealand, for example, responded to the oil price shocks (and the simultaneous loss of preferential access to the UK, its largest export market) with expansionary macro policy and protectionism to support self-sufficiency. Relatively little effort (beyond diversification of export markets) was made to respond to structural changes underway. This did not end well. Massive economic reforms were required from the 1980s to begin to address the problems created.

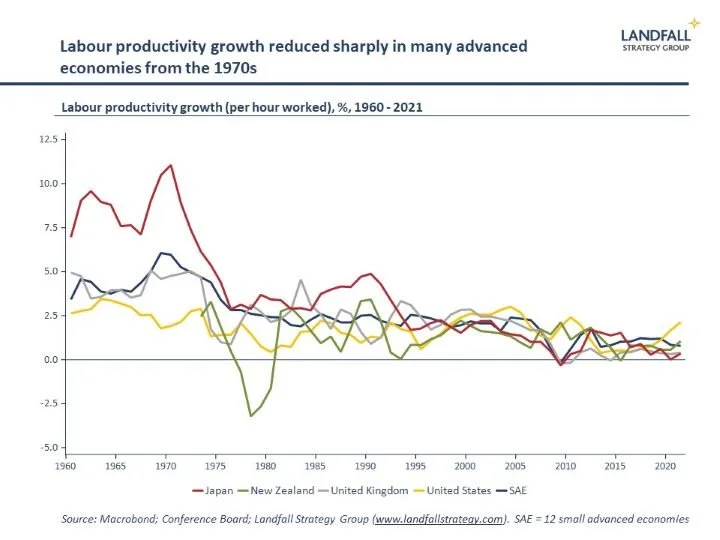

The New Zealand example is perhaps extreme, but it is not unique – directionally similar policies were adopted across many advanced economies. It is instructive that labour productivity growth began to decline across advanced economies from this time.

This experience cautions against over-reliance on macro policy to respond to the current economic challenges. The risk of poor economic outcomes such as stagflation will be higher if governments rely too much on fiscal stimulus to support economic activity (which can create inflationary pressures if bottlenecks in the economy persist); or on increasing interest rates to control inflation that is due to supply-side constraints (which can lead to sharp contractions in economic activity).

The supply-side shocks require supply-side responses, as well as a high pressure economy. For example, governments should be investing to expand productive potential: in renewable energy, to improve the resilience and efficiency of energy systems; in upgrading skills and supporting the movement of labour across the economy, so that people can take advantage of new opportunities; and supporting business investment in new technologies that will enhance labour productivity.

Similarly, the approach to strategic autonomy and supply chain resilience should be based on the disciplined management of exposures rather than de facto protectionism.

The silver lining

Setting government policy and company/investment strategy is difficult in periods of regime change. Deliberate strategic responses are needed to structural change, in the presence of substantial uncertainty.

But despite the many and obvious challenges, there are opportunities as well. There is potential for a post-Covid productivity renaissance in countries and firms that invest heavily in technology and new business models. Indeed, the challenging 1970s saw the birth of companies like Apple and Microsoft – and the development of the successful East Asian growth model.

Countries and firms that adapt most quickly to the new economic regime are likely to perform well. Strategic agility and responsiveness become key assets in periods of disruptive change.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Feel free to get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

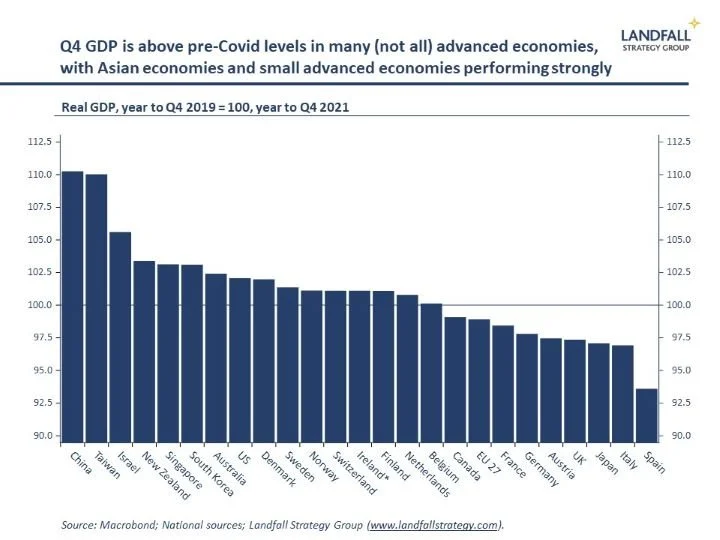

Q4 GDP data have now been released across all advanced economies. Two years into the pandemic, the divergence in economic performance is clear. Many Asian economies, such as China, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea – as well as Australia and New Zealand, have performed particularly well. And small advanced economies have markedly out-performed their larger counterparts. Of the G7 economies, only the US has recovered to its pre-Covid levels of GDP.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling