The first world economic war

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

For all the materiality of the economic shock due to Covid – G20 GDP contracted by 9% in the year Q2 2020 – government policy and successful vaccines were able to support a rapid global economic recovery. But after dealing with pestilence, the world is now confronted with the economic consequences of war: a man-made economic crisis caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

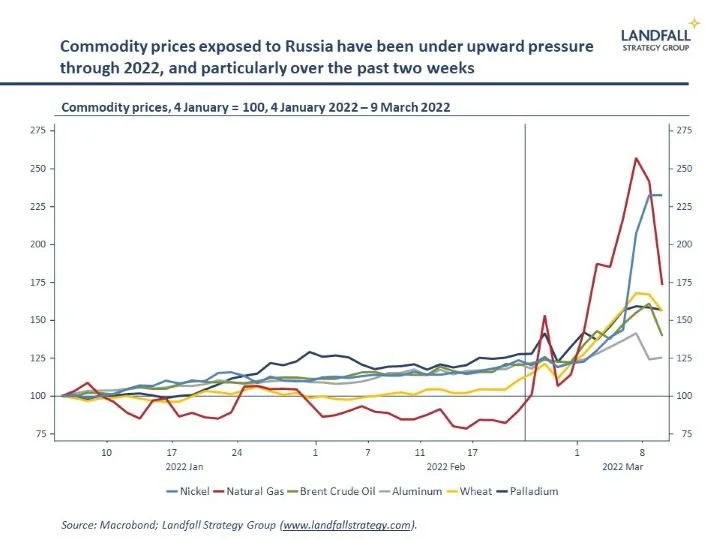

Global economic forecasts are being marked down, and inflation forecasts are being marked up, on the back of soaring energy and commodity prices. And in a structural sense, the Russian invasion and the international response will reshape the functioning of the global economic system. This is the ‘end of the beginning’, as I noted recently.

War by other means

The initial Western response to the Russian invasion was to provide additional military support to Ukrainian forces, who are fighting with remarkable courage and results. But over the past week or so, this has become an economic war against Russia for the US, Europe, and its partners. French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire talks of ‘economic and financial total war against Russia’.

After an initial round of aggressive economic sanctions, such as disconnecting selected Russian banks from SWIFT, freezing Russian central bank assets, and imposing penalties on Russian institutions and individuals, this week has seen further economic pressure applied. The US and UK are banning Russian oil imports; restrictions on technology engagement with Russian firms are being extended (e.g. semiconductors); and there is increased freezing/seizure of assets (anyone want to buy Chelsea?). More is likely to come.

The exit of Western firms from the Russian market continued this week, including Goldman Sachs, Visa and Mastercard, as well as Starbucks and McDonalds (in a reminder that Tom Friedman’s ‘Golden Arches’ theory hasn’t aged well).

Choices such as banning Russian oil imports would have been unthinkable even a month ago. But at least for now, there is a political willingness to absorb economic costs – notably higher energy costs – in order to confront Russia and resist the challenge to the rules-based global system.

Although economic sanctions are not new, it is striking that a broad coalition of countries has imposed sweeping sanctions on a G20 economy (Russia was the 11th largest economy in the world in 2021) that has significant positions in exports of energy, food, and other key commodities.

This is the first meaningful conflict being (partly) fought using economic instruments in a deeply integrated global economy: it is perhaps the ‘first world economic war’, with effects stretching from New Zealand and Singapore to the Middle East and Europe. We are in uncharted waters.

These sanctions dramatically increase the costs borne by Russia, even if it is unlikely to immediately alter Mr Putin’s decision-making. Indeed, yesterday’s meeting between the Russian and Ukraine Foreign Ministers confirmed that the Russians are not yet approaching negotiations seriously. But the unexpectedly strong set of economic sanctions will likely deter future adventurism by Russia and others.

Global impact

Although the sanctions are focused on the Russian economy, which is in freefall, there will be broader costs as a G20 economy is removed from parts of the global economy. Higher inflation and reduced economic activity across much of the global economy is inevitable for a time, as global energy and commodity flows are disrupted.

Many of these costs are due to the direct impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. For example, the production and distribution of commodities such as wheat and fertiliser have been hugely disrupted by the invasion, creating concerns about global food security. And oil and gas prices were moving sharply higher before sanctions on concerns about Russian supply.

These disruptions have been reinforced by sanctions: the ban on imports of Russian oil from the US and UK effectively reduces global supply; and participants in other commodity markets in which Russia has significant positions are more often unable/unwilling to transact with Russian counterparties. Russia has now threatened bans on exports of selected commodities, which could place further pressure on prices and global supply chains.

Concerns about the unwinding of the ‘great moderation’ due to these frictions on globalisation is a key reason why financial markets have sold off so heavily. The 1973 oil price shock that followed the Yom Kippur war in which oil prices increased by ~3x in six months, contributing to stagflation (and political instability) in many advanced economies, is an imperfect analogy. But these risks should be taken seriously. Inflation in the US (7.9%) and Eurozone (5.8%) is already at multi-decade highs, and growth in economic activity is slowing.

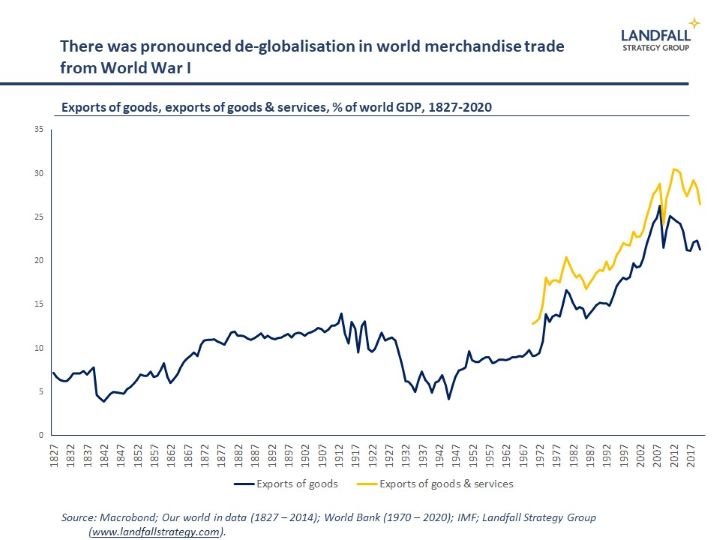

Beyond these substantial near-term costs, the invasion and the policy response will lead countries and firms to reduce economic exposure to countries with which political disputes may arise. This will accelerate the drive for strategic autonomy in supply chains as well as economic and financial decoupling.

I don’t expect de-globalisation of the type seen after WWI. But there will be meaningful change in the pattern of global flows – much more shaped by political factors, and more regional in nature.

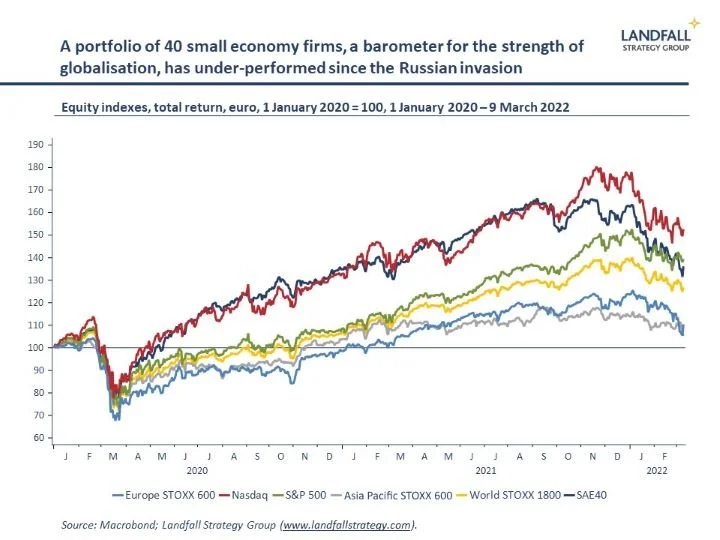

One indication of the current challenges to globalisation is the relative performance of small advanced economy markets; the canaries in the mine of the global economy. I have created a portfolio of 40 large, globally-exposed firms from a range of small economies, that provide a barometer of the strength of globalisation.

This small economy portfolio has performed strongly through Covid (and prior) but has under-performed over the past few months – and notably since the Russian invasion (down by ~10%). This weak recent performance of small economy firms suggests structural change in the global economy.

And several small economy markets that are traditionally highly sensitive to globalisation have also sold off. This is partly due to Russia-specific exposures, but also their broader exposure to the global economy. However, small advanced economies are resilient, and I am confident in their ability to adapt to new global realities.

What next?

Although economic war has been deliberately chosen because of the scale of Russia’s challenge to the rules-based global system, it will inevitably have far-reaching effects on the functioning of the global economy.

Whereas the physical conflict in Ukraine will eventually end, this economic war will be very long-lived – it has its own political logic. The formal sanctions will be in place for a long time – at a minimum, until the Russian invasion is reversed, and perhaps Mr Putin is gone. But even if/when sanctions are lifted, the drive for economic independence from Russia (notably in energy) will continue. And many companies will be reluctant to return rapidly to the Russian market due to stakeholder pressure.

More broadly, precedent has been set for the use of sweeping economic sanctions. The US, Europe, and others will increasingly use trade, investment, and technology instruments, in strategic competition with their rivals.

As regular readers will know, my baseline case is for a fragmented global economy to emerge along the fault-lines of competing political poles. These realities mean that companies will need to take geopolitics more seriously in their strategy and capital allocation processes.

And governments will need to manage national external exposures, invest in building strategic autonomy and supply chain resilience (military, energy, and so on), and manage the distributive consequences of disrupted global flows (higher energy, food prices). The highly open European economy is ground zero for these policy debates. The EU meetings hosted by President Macron in Versailles yesterday and today will provide a perspective on emerging policy thinking on these issues.

The brutal and misjudged Russian invasion of Ukraine has permanently changed the global economic and political context. Expect significant costs as global flows are disrupted, and also the emergence of a more explicitly political global economic system. There is no going back.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Feel free to get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

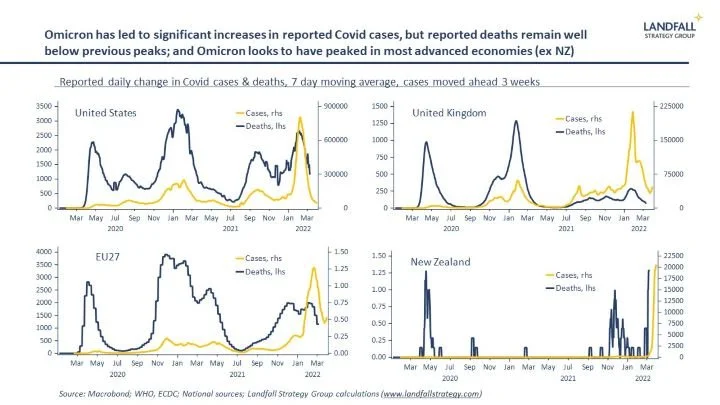

Omicron has shifted the dynamics of Covid. In many advanced economies, cases were well above those of previous waves – although deaths remained relatively low. This reflects high vaccination rates in many advanced economies as well as the apparently less serious nature of the Omicron variant. New Zealand is a clear exception, opening up after moving away from its strict control approach. Omicron looks to have peaked in most advanced economies, and many government are well on their way to lifting all or most remaining restrictions.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling