Fault lines in the global economy

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Coming from New Zealand, I am unfortunately used to earthquakes. After the main quake, aftershocks (some very large) are common. And after the tectonic shock of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there has been a rolling series of aftershocks as the global economic and political system reconfigures.

Big power wars (as with pandemics) put pressure on fault lines in countries and in the global system. My assessment is that the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the Western-led response, represents a rupture in the global economic and political system. These tectonic changes will play out over long periods, but the speed and scale of the aftershocks are already striking.

The global economy is fragmenting along political lines. Events over the past week or so provide more indications of the characteristics of this emerging environment.

The West renewed?

The scale of the Western-led response (economic, military, political) to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has surprised relative to initial expectations. And there are some signs that economic and political relations between countries in the Western orbit are strengthening.

The Russian invasion has redrawn the strategic architecture across Europe: NATO has been reinvigorated, and there are commitments to increase military spending.

On Thursday, the Finnish President and Prime Minister recommended that Finland apply for NATO membership. This application has political support, and will happen – and will be approved by NATO. Sweden is likely to follow suit next week. Security guarantees have been provided to Finland and Sweden for the interim period until they become NATO members.

The EU is using economic instruments to extend its reach. The EU has offered tariff-free access for Ukraine, for example, and is looking to accelerate FTAs with Australia, New Zealand, and others. And this week President Macron suggested a looser grouping of European countries on the periphery of the EU that could receive some of the benefits of EU membership – a way of integrating with countries that may not achieve full membership.

In Asia, several countries implemented sanctions on Russia (including Singapore, Japan, and South Korea). And Japan has been expanding its intelligence sharing arrangements with ‘five eyes’ countries, most recently with New Zealand.

There are risks to Western coherence of course. The US is the dominant member of the West; it has been central to the military and economic support of Ukraine (legislating a total of over $50 billion in support so far). But it is not clear whether a future US Administration would be as committed to these alliances (refer my note last week). And there are differences in Europe on how to approach China; note the calls between President Xi, President Macron, and Chancellor Scholz last week.

Although it will be a bumpy process, tighter strategic relations across the West and ‘friend-shoring’ (per Janet Yellen) of economic relations look likely to expand.

Choosing not to choose

But this fragmentation of the global economy is not simply a binary split between the West and China/Russia. The UN voting patterns show that between the Western-led group of countries and China/Russia lies a large middle ground – from Asia (India, many ASEANs) to the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America - together accounting for over half of the world’s population. These countries are looking to avoid having to make choices between the West and China/Russia. Not everyone is ‘doomed to choose’.

This is where ongoing action is likely to persuade countries on their positioning. India, the largest of the non-aligned, has been invited to the German-hosted G7 meetings in June; and Mr Modi has recently been in Europe for meetings. The US is offering India more in terms of military relations, and India is engaged in the Quad grouping.

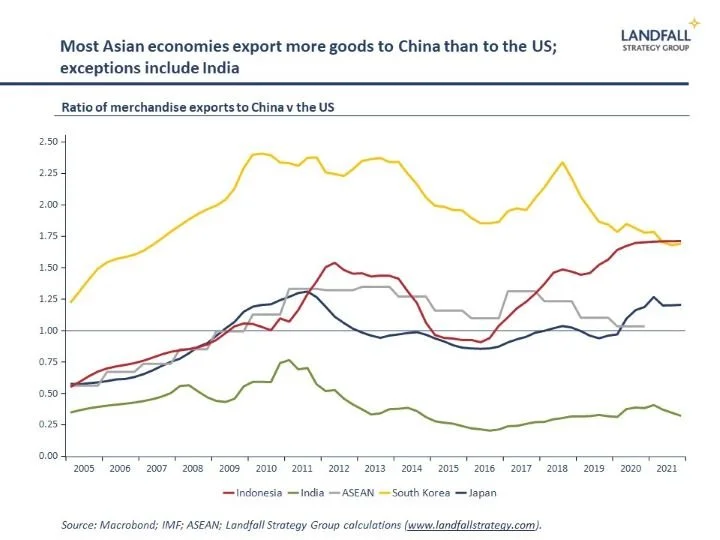

ASEAN leaders are in Washington for a US/ASEAN summit yesterday and today, hosted by President Biden. Most of the ASEANs abstained from the various UN resolutions on Russia (Singapore was an exception) and are reluctant to join any coalition aimed at China, their largest trading partner. But many value the security backstop provided by the US.

The problem is that the withdrawal of the US from the CPTPP has left the US without a credible economic agenda in Asia; and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework currently being offered is a pale imitation. For the ASEANs, together with others in the region like Japan and South Korea, these economic considerations weigh heavily – and will limit the ability of the US to forge a strong, broad coalition in Asia. To understand geopolitics, it pays to follow the money.

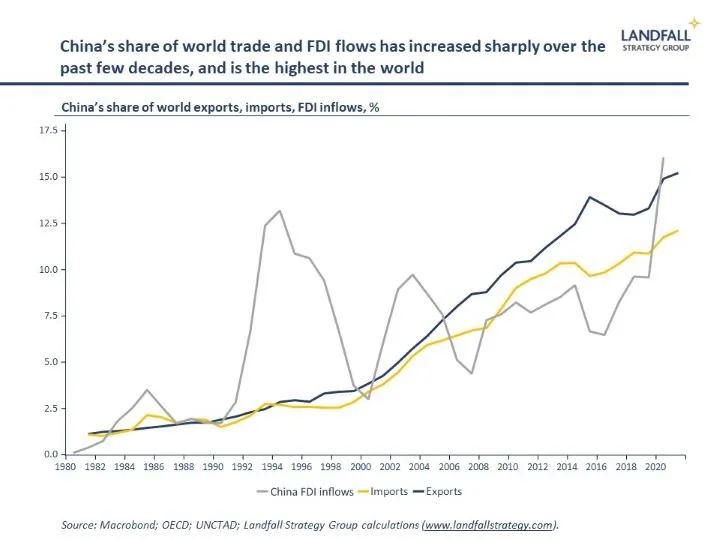

And China, of course, is using its economic weight to strengthen economic and political relations with a broader group of countries. Figuring out the location of these political contours is central to understanding likely future patterns of global trade and investment flows.

The costs of fragmentation

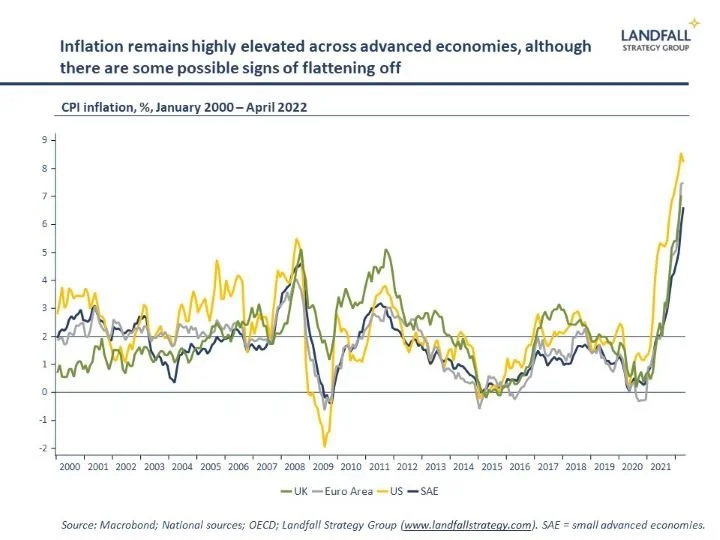

A fragmented global economy is more costly and inefficient, due to additional frictions, disrupted global supply chains, and so on. Indeed, energy, food, and commodity prices remain highly elevated – contributing to the ongoing surge in inflation (refer chart of the week, below).

The economic shock plus the inflationary impulse is causing concerns about stagflation; central banks are raising interest rates into a weaker economic context. These stronger economic headwinds have been a catalyst for the equity market selloff.

A meaningful decoupling from China over time would be more costly again. Some decoupling is underway already, and more is inevitable as geopolitical tensions continue – although China’s scale and centrality means it cannot be sanctioned as completely as Russia.

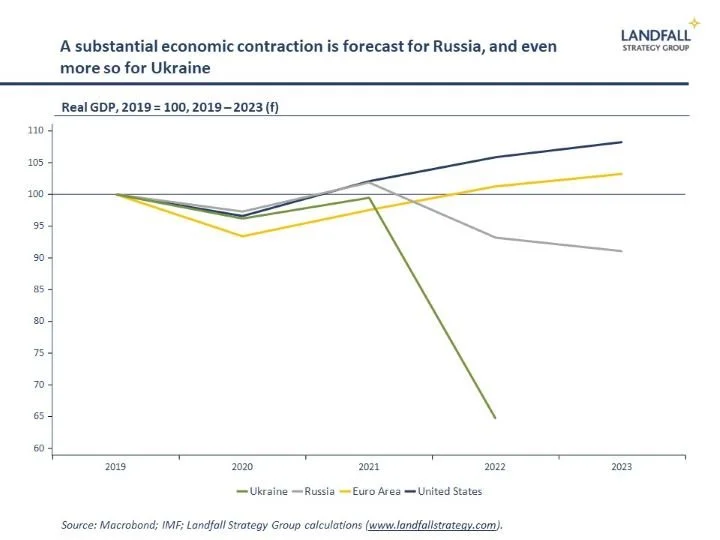

At a national level, Russia has effectively cut itself off from the global economy with a new Iron Curtain. Russian economic data so far is better than initially expected: the currency and interest rates have stabilised on capital controls, and income from oil and gas exports is helping Russia’s economy.

But Russia’s GDP is forecast by the IMF to contract by ~9% this year (and likely by more), there was an outflow of 3.8 million people from Russia in Q1 (~2.5% of the population), its technology sector can’t function, and it has destroyed the major market for its gas exports. The Victory Day ceremonies in Russia this week – and Mr Putin’s speech – were muted for reasons beyond military failures.

And for Ukraine, the invasion plus the involuntary decoupling from the global economy is an economic catastrophe. GDP is forecast to contract by over a third this year, with a reconstruction bill currently estimated at €200bn-500bn, >3x Ukraine’s pre-war GDP. However, post-war, Ukraine is likely to benefit from moving into Europe’s economic orbit.

A new world

We are in the early days of a new global economic order emerging, but some of the characteristics are becoming clearer. The costs and disruptions of a more fragmented global economy are immediately evident.

Although I remain generally positive about the resilience of globalisation – it is changing shape rather than reversing – these global frictions will be challenging for (small) economies that are deeply exposed to global flows. Looking forward, global flows will be increasingly shaped by political factors (‘values-based globalisation’). These political fault lines in the global system are beginning to emerge.

There is much uncertainty. But it is clear that this will be a very different global economy than over the past few decades.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

US inflation came in this week at 8.3% for the year to April, slightly down on the March reading – but higher than expected. And inflation remains high in the Eurozone (7.5%) and the UK (7.0%). Across small advanced economies, deeply exposed to the global economy, inflation is also at elevated levels (6.6%). This is importantly driven by food and energy prices. Core inflation, which strips this out, is lower: ~3% in the Eurozone, and just over 6% in the US.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling