Too much of a good thing

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

It has been another turbulent week. The S&P 500 is close to bear market territory, partly on concerns about higher interest rates and inflation; China’s Covid lockdowns continue to have major disruptive impacts; Sri Lanka is in financial distress, out of dollars and fuel; Finland and Sweden formally applied for NATO membership; and the EU announced measures to decouple from Russian energy.

These and other developments indicate that we are entering a new, less benign, global environment. As recent notes have discussed, the global economy is fragmenting along political fault lines amid rising geopolitical tensions and there is a growing array of economic and political risks.

Countries and institutions that are highly leveraged to the previous global system face significant exposures. Hard choices will be needed to adjust to the ending of the golden economic and political weather.

Path of least resistance

We are entering a new world after a prolonged period of good times, with strong income and wealth growth, geopolitical stability, and intense globalisation.

The sustained period of good times over the past few decades has encouraged firms, investors, and governments to develop positions that are highly exposed to the prevailing regime. Even when risks were identified, the compelling nature of near-term returns, coupled with a growing measure of complacency, has frequently led to the path of least resistance being taken.

‘When the music stops… things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing’, Chuck Prince (Citi CEO), 2007.

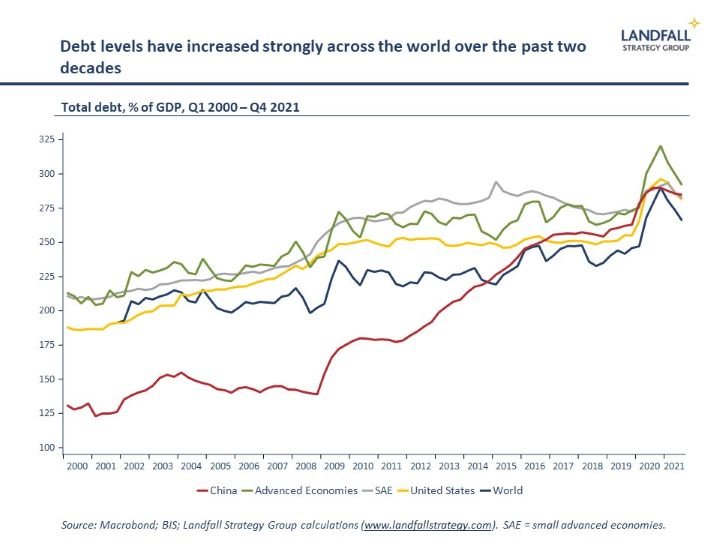

For example, sustained low interest rates and expanding central bank balance sheets have underpinned soaring asset prices around the world, from equities and credit to real estate and beyond. And debt levels in both the public and private sector have increased substantially. The ‘central bank put’ was seen to de-risk investment in financial markets. Borrowing and investing was good advice for much of the past few decades.

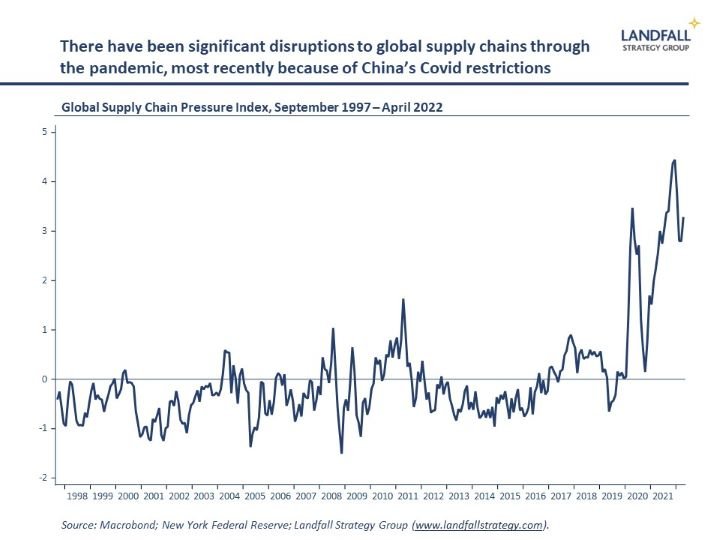

Similarly, many global firms created far-flung supply chains in pursuit of operating efficiencies. Production was located in China and other emerging markets, reliant on an increasingly complex system of international logistics. This has worked remarkably well, acting as a significant global deflationary force and supporting firm profits. Although this system is vulnerable to disruption, firms generally did not see the business case for paying a premium for resilient supply chains.

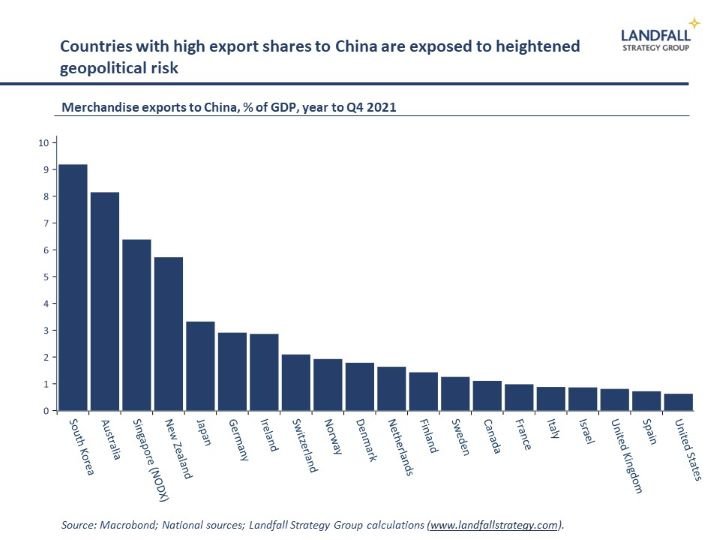

A third class of exposure is to geopolitical risk. On assumptions of tolerable geopolitical stability (or some hope of Chinese reform), many Western economies have become deeply exposed to China – as an export market, a production platform, and as source or destination of investment capital.

And despite the growing frictions between the West and China over the past decade, from the trade wars to Chinese sanctions, the trade and investment relationships continued to grow. From Europe to New Zealand, China was seen as a commercial opportunity – with political issues able to be quarantined for the most part. Indeed, those countries that maintained the more stable political relations with China now have particularly deep economic exposures to China.

And in Europe, Russia became embedded as the dominant energy supplier as a matter of deliberate policy: the economic advantages of low cost energy, and the desire to support political relations with Russia. Geopolitical risk was downplayed by most European countries, notably Germany.

Swimming naked

‘Only when the tide goes out do you discover who's been swimming naked’, Warren Buffet

An economic and political regime change is underway, which will create exposures for those that are heavily leveraged to the aspects of the system that are changing.

The expectation of higher interest rates is hammering equity and bond markets, for example. Although I don’t think interest rates will return to pre-GFC levels, those that are reliant on super-low interest rates and QE will face challenges. Governments and institutions that have high levels of debt are exposed.

Similarly, there will be growing action to strengthen the resilience of global supply chains. Events like the blockage of the Suez Canal last year and the ongoing pandemic-related disruptions to global supply chains have focused the minds of companies and governments. Firms with more resilient supply chains have been advantaged over the past two years. Many firms report greater interest in re/near-shoring activity, diversifying production bases, building inventories, and so on.

But the most significant set of exposures to a changing world is through the intersection of geopolitical risk and commercial relations. In a fragmenting global economy, where trade and investment flows are increasingly shaped by shared political values and interests, there will likely be a rebalancing across key markets: trade and investment will increasingly occur between friends (note another speech by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen this week).

This will be challenging and costly for Western economies that have developed deep economic exposures to China. In many cases, there are few/no near-term substitutes for markets of China’s scale. And recent events show the near-term costs involved in Europe moving away from Russian oil and gas.

Hard choices ahead

Over the past few decades, countries, firms, and investors, have optimised their approaches to the prevailing global economic and political regime. Now that the regime is changing, these approaches will need to be changed as well. It would be surprising if the world changed but government and firm strategy required no change. In general, the more rapidly firms and governments adjust to a new world, the better.

But this is not an easy transition. Big investments have been made in the old world, which will be costly to unwind. And there is uncertainty about exactly what this new world will look like, how rapidly it will emerge, what competing countries firms/investors are doing.

Given that loss aversion is one of the more powerful behavioural biases (where losses are weighted more heavily than equivalent gains), it may be that there is a tendency to adapt only gradually. Inertia is a very powerful force.

‘When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?’, quote often attributed to John Maynard Keynes

Indeed, some will argue that it was right to take full advantage of access to cheap Russian energy, Chinese demand, or low interest rates; and that a pivot should only be made when change is evident. But this argument downplays the costs involved in changing. If a continuation of the status quo leads to further exposures accumulating, the eventual change will be more costly and disruptive.

By the time that facts change definitively, it may be too late. You may find yourself with diminished options, with reduced ability to change.

The same logic applies to the net zero transition, another major structural change underway. Although this transition will involve costs, there are also opportunities – and these are most likely to be captured by the early movers.

Overall, governments, firms, and investors need to deliberately adapt to a new economic and political regime. Exposures that have been accumulated – from high debt and emissions levels, to fragile global supply chains and economic exposures to geopolitical rivals – need to be managed (and not increased further).

Deliberate action is required by firms and governments to respond to the structural changes underway: building options, altering areas of strategic focus, exiting some markets and business models, investing in new growth areas, and so on.

This may require breaking with the short-termism of stakeholders, that may prefer to stick with a version of the current model. The quality of these decisions will be a first-order driver of future performance.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Elsewhere

I joined Amar Breckenridge from Frontier Economics last week for a new podcast series on international trade and economic issues. We talked about the implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the fragmenting global economy, Brexit, and values-based globalisation. A link to the podcast is available at: https://www.trade-knowledge.net/podcasts/

Chart of the week

Iron ore and dairy prices have weakened markedly over the past several weeks. Despite their differences, these hard and soft commodities have tended to move together because China is the marginal buyer. So the weakness in iron ore and dairy prices says something about a broadly slowing Chinese economy; iron ore prices were also impacted by restrictions on the real estate sector last year. This is an exposure for Australia and New Zealand, big iron ore and dairy exporters respectively.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling