Davos, guns & butter

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

This week’s Davos meetings – a good guide to the zeitgeist – had a different tone than previous years. President Zelensky spoke on the opening morning; sessions on geopolitics were heavily attended; and there were widespread concerns about deglobalisation.

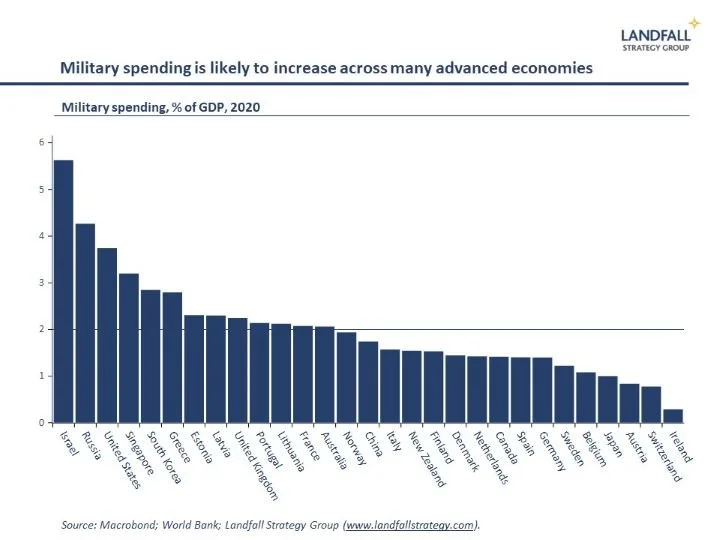

In light of Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent Western sanctions, the change in the global (or at least Western) consensus is understandable. NATO has been reinvigorated; commitments to increased military spending have been made; and politics is shaping economic engagement. In Econ 101 framing, there is a shift from butter to guns.

My recent notes have argued that we are moving to a more fragmented global economy, with fault lines arranged around political divisions. Countries and firms need to adapt: strengthening supply chain resilience, actively managing geopolitical risk exposures, and so on.

Domestic and international politics were not treated as seriously as they should have been in the global economy over the past few decades. This complacency generated costs in terms of heightened exposures. A rebalancing is needed. But there are risks of an over-correction. An over-weighting of politics in approaches to globalisation will also be costly.

Slouching towards autarky?

Geopolitical and domestic political are challenging aspects of global economic integration. For example, there are more examples of Western trade, investment, and technology decoupling from China. Flows to/from China have continued to increase, but restrictions are likely to strengthen over time. And China is turning inwards, reducing its exposure to the West.

There are also growing domestic political pressures for increased self-sufficiency. Successive US Administrations have imposed tariffs and local content requirements, to incentivise local production of manufactures and technology. These political pressures have been reinforced by the global supply chain disruptions over the past few years. In Europe, Mr Macron and others talk of strategic autonomy.

There are often good reasons for firms and countries to strengthen supply chain resilience. But at a national level, there are risks that the supply chain resilience argument is taken too far. The policy choices of larger economies to increase strategic autonomy may accelerate the fragmentation of the global economy (see a good speech this week by Singapore’s PM Lee). Self-sufficiency is likely to be costly, particularly for smaller economies.

Geopolitical realities mean that the global economy will fragment. But the extent and nature of this fragmentation is partly a matter of choice. If trade and investment flows are increasingly shaped by ‘friend-shoring’, committing to open flows within broadly-defined groups of friends is valuable: an ‘open strategic autonomy’ approach. Decoupling is not an absolute, and there should be a bias to openness where this is possible.

But there has been an unfortunate tendency to define these policies narrowly. For example, US trade measures over the past several years have set up economic conflicts with Europe and with its Asian partners. The risk is of a slippery slope to protectionism, where economies respond to a more challenging global context by increasingly hunkering down behind borders.

Guns first?

A second risk of political over-correction relates to the nature of big power competition. This week, the US announced its Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) during a trip to Asia by President Biden. This is a welcome but flimsy substitute for US involvement in the CPTPP, from which it withdrew under President Trump. The IPEF offers a framework for cooperation on issues from supply chain resilience to clean energy and infrastructure, but offers no US market access. The Asian response has been positive but muted: it is better than nothing, but not by much.

US engagement with Asia is increasingly heavy on security engagement, organised around strategic competition with China, through groupings like the Quad and AUKUS. Security engagement is valued by many countries in the region, but it is unbalanced without a strong economic element.

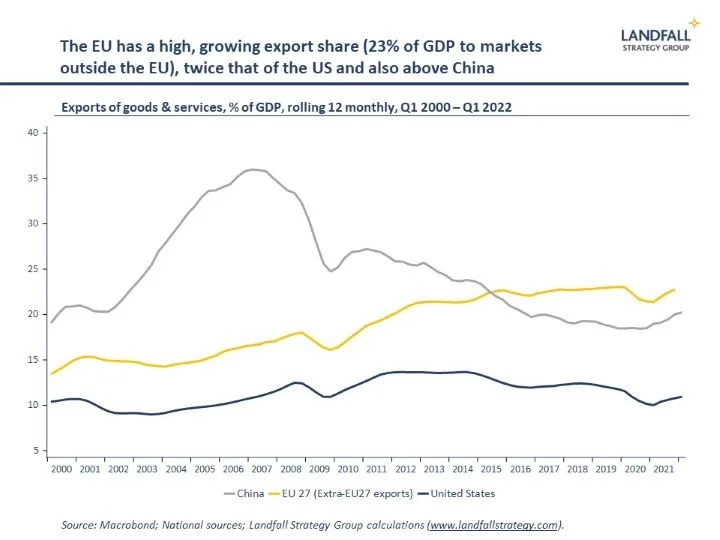

Part of this US policy approach is due to the perceived failure of its economic engagement model with China over the past few decades: this did not deliver desired outcomes, and exposed US labour markets to disruption. The US also emphasises hard power because it is a relatively closed economy compared to Europe and China.

China continues to aggressively use its economic weight to advance its interests. China is the largest export market for countries in Asia (and beyond); is a founding member of RCEP; has trade and investment agreements with countries around the region; and has pursued (patchy) economic integration through the BRI.

But this is increasingly coupled with an aggressive approach to military and diplomatic relations, even as China’s economy slows. Just this week, China conducted strategic bomber exercises with Russia over the Sea of Japan; and Chinese plans to establish a much stronger presence in 10 Pacific Island states were revealed (alongside its recent deal with the Solomon Islands).

None of this is surprising, as a rising power competes with the incumbent. But the dominance of the US, and more recently of China, is built on economic and technological success. Positions built primarily on guns not butter are less likely to be sustained - and will likely weaken the global economic system.

The king is dead, long live the king

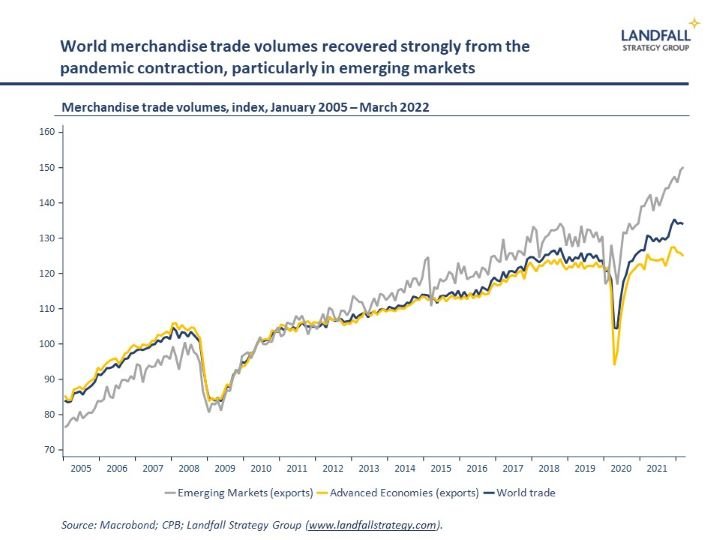

Although my assessment is that there has been a rupture in the shape of globalisation, as we move to a more fragmented global economy, I also judge that the death of globalisation is exaggerated (as I noted in January; see also this good FT piece by Martin Sandbu yesterday). Globalisation is changing structurally, but the rhetoric of deglobalisation runs well ahead of current reality.

Global merchandise trade flows have been resilient through the pandemic; bilateral flows continue to grow between China and the West; and near-shoring activity, often wrongly interpreted as synonymous with deglobalisation, is not yet happening at a scale to be economically meaningful.

Over time, trade and investment flows will become more regional as supply chains compress; and will be increasingly shaped by shared political values as geopolitical pressures strengthen. But this is not necessarily deglobalisation: it is the emergence of a more regional model of globalisation. There will be additional costs and frictions, but the hyper-globalisation of the past few decades is not the only possible model of globalisation.

However, the risk with over-interpreting the political headwinds to globalisation is that large countries (and firms) may reduce the policy commitment to externally-oriented growth, focusing on domestic market opportunities and withdrawing support for international institutions. This could make deglobalisation a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But for most economies, global markets will remain an important source of productivity and innovation. Countries and firms are better advised to aggressively adapt. Indeed, many small advanced economies – that are deeply exposed to global dynamics – are responding by increasing investments to build deep positions of competitive advantage, while also managing emerging risks (supply chains, geopolitics).

Choices matter

The regime change underway in the global system is not a deterministic process. Choices can be made that manage the costs and risks of a more fragmented global economy – or that worsen them. Global trade and investment flows will almost certainly be diverted and reshaped; policymakers need to make sure they are not destroyed. The risks of deglobalisation are manageable - but they need to be managed.

If complacency around the interaction of politics and globalisation has been a major failing over the past few decades, the bigger risk now is of fatalism around deglobalisation - that governments and firms choose to look inwards, believing that an unwinding of globalisation is inevitable given the political context.

Instead, determined efforts should be made to shape national and international policy approaches that can capture the significant benefits from global flows even in the context of new political challenges.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

I provide advisory services and deliver presentations on global economic, policy, and geopolitical issues, for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do get in touch if you would like to discuss these services.

Chart of the week

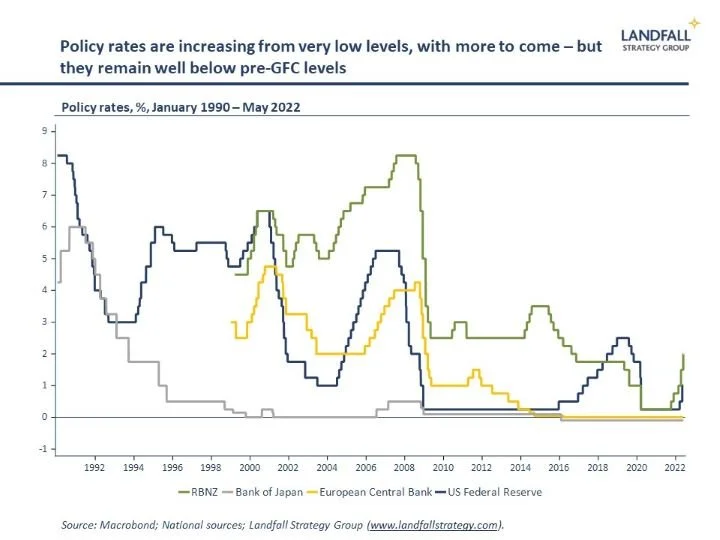

Policy rates continue to increase around the world in response to surging inflation. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand increased policy rates by 50bp during the week; and the ECB signalled rate increases to come by Q3. The issue is whether this represents a structural break from the declining profile of policy rates over the past 30 years. Central banks have encountered increasingly tight limits in raising rates over this period.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling