Geography is not history

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Global economic geography has become more distributed over the past several decades, with global supply chains knitting together global production networks. But disruptions from the pandemic, combined with rising geopolitical rivalry and the net zero transition, will structurally change the geography of globalisation.

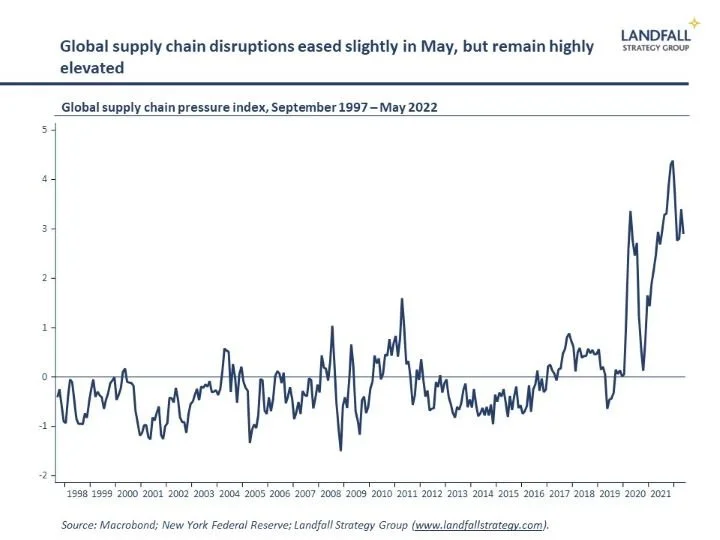

Recent global supply chain disruptions have reminded that far-flung supply chains are a source of economic risk. And weakening labour cost advantages in many emerging markets and the enhanced ability to use technology to produce closer to home reduces some of the attraction of global supply chains.

This increasingly regional global economy will be reinforced by geopolitical frictions, with decoupling likely to become more pronounced. Increasingly, trade and investment flows will be shaped by political relations; and a more fragmented global economy is likely.

Further reinforcement is likely from the net zero transition. The growth in renewable energy, which tends to be highly local, will displace internationally-traded flows of fossil fuels over time. And emissions pricing (and shifting consumer/firm preferences on emissions) is likely to put pressure on activities such as long haul air travel and international shipping.

So far, there is little evidence of a reduced average distance of trade or of increased intra-regional trade within groupings like ASEAN or the EU. But regionalisation dynamics in global geography are likely to strengthen. Firms and countries will need to respond to the economic consequences of this shift.

Winners & losers

One of the biggest winners from the globalisation of economic activity over the past several decades have been East Asian economies: their export-oriented growth models have supported strong convergence towards the per capita income frontier.

But looking forward, as global supply chains retreat, Asian economies will likely have to reorient towards the Asian consumer market. It is less likely that the next generation of Asian growth economies will be able to follow the same global supply chain-driven growth model of the Asian tigers.

However, some Asian locations will benefit as firms diversify supply chains out of China. Apple recently announced that it is moving some iPhone production into Vietnam out of China, partly motivated by supply chain disruptions in China. Expect more of this.

The global centre of economic gravity will likely continue to move towards Asia. But although the largest agglomeration of economic activity will be in Asia, in a fragmented global economy this does not mean that global trade and investment flows will be anchored in Asia. Asia will become more Asian, with stronger regional flows.

We will likely see strong growth in other geographies that are adjacent to large consumer markets. Mexico, for example, is currently seeing strong inward investment flows from companies looking to produce for the US market, partly in response to global supply chain disruptions. Similarly, locations on the periphery of Europe will likely benefit in a similar way to the central and eastern European economies from the 1990s, which leveraged low cost structures and proximity to Europe.

The global economy out of sync

Intense globalisation over the past few decades has been accompanied by an increasingly synchronised global business cycle: the tight global network of trade and investment flows means that economic shocks propagate around the world.

These global co-movements are clearly seen in small advanced economies. My calculations show a tight relationship between world GDP and trade growth and national-level export and GDP growth in small economies.

A more fragmented global economy will likely lead to a less synchronised global business cycle. Economies will be more exposed to the strength of the regional economy rather than to the overall global economy; their external exposures will likely be more volatile, as they will be less diversified across regions; and there will be a greater dispersion of economic outcomes around the world as countries are impacted by different idiosyncratic shocks.

European economies will be exposed to European shocks, Asian economies to Asian shocks, and so on. But the profile of risks is unlikely to be even across geographies.

One of the biggest risks in the global economy is the economic trajectory for China. China accounts for ~13% of world (merchandise) import demand, ~19% of global GDP, and 25-30% of annual global GDP growth.

In the near-term, Covid restrictions are hitting the Chinese economy: both the OECD and World Bank marked down China’s growth outlook significantly this week. Indeed, some forecast that the US will out-grow China this year for the first time since 1976. And over the longer-term, there are headwinds to Chinese growth (contracting working age population, capital misallocation) as well as political and geopolitical risks.

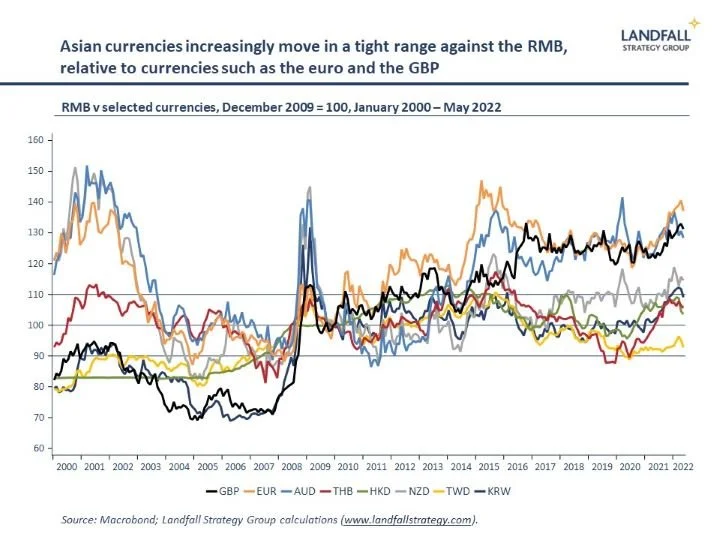

But as China decouples from Western economies, these exposures to the Chinese economy will increasingly be felt in Asian economies. Of course, China’s scale means that a China shock will remain a global event – but fragmentation of the global economy will reinforce the regional impact of the shock. Indeed, many Asian currencies move in an increasingly tight range against the RMB.

Strategic economic deals

These emerging economic ‘blocs’ will not be closed; the economic logic of globalisation remains powerful, which will ensure inter-regional trade and investment flows continue – just not at the same intensity.

And geopolitical blocs do not align perfectly along regional lines. Most notably, there are several Western-aligned economies in the Indo-Pacific – from Japan and South Korea to Australia and New Zealand. These economies have strong economic links in the region, but have strategic/security links with the US and Europe, and want to manage China exposures. The ‘friend-shoring’ idea implies ongoing economic relations (trade, investment, technology flows) between these physically distant economies.

Although many trade agreements are explicitly regional in nature (CPTPP, RCEP, and others), it is likely that trade deals will increasingly be framed in strategic terms to tie together political ‘friends’. This might be seen in deals such as the US-led IPEF (although this is very modest), as well as bilateral agreements such as various US trade deals (Japan, South Korea, Singapore) and the EU’s current trade negotiations with countries such as Australia and New Zealand.

Strategic economic/trade deals will provide important institutional scaffolding for friend-shoring, and will offset some of the tendency to regional flows. This will provide options for firms/countries in the Indo-Pacific that want to manage economic and geopolitical risk exposures.

The WTO Ministerial meetings in Geneva next week are unlikely to deliver anything of great substance; the future will be in these bespoke deals between friends.

Flat world no more

‘Geography is destiny’, quote often attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte

Globalisation is continuing, but it will be more regional in nature. We will see an archipelago global economy, with agglomerations of economic activity that are less tightly connected.

Geography is not quite economic destiny, but physical location will increasingly shape trade and investment options as well as economic exposures. This is not new – gravity models already explain trade and investment flows well – but it will become more acute. For many countries and firms, the world will become a smaller place.

This will vary by sector – some activities are less constrained by geography than others – as well as the extent to which national economic and political interests align geographically. Global strategy for countries and for firms will increasingly need to grapple with positioning for these emerging geographic realities.

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

Chart of the week

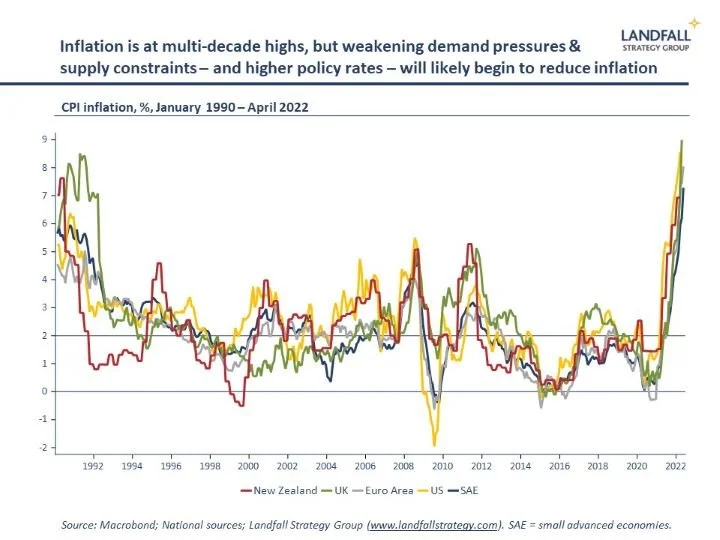

Inflation rates have continued to move up to multi-decade highs, although with a slight moderation in the US in April. The OECD, World Bank, and the ECB, marked up inflation forecasts this week: higher inflation will be more persistent than initially expected. On Thursday, the ECB committed to begin to reduce its large balance sheet and to lift the policy rate from July. And other central banks (such as Australia, New Zealand, Israel, South Korea), have raised rates over the past two weeks.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling