Brexit, Biden, & turning points

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

2016 was a pivotal year in the political backlash against intense globalisation. The combination of the Brexit vote (‘take back control’) and the election of President Trump (with an America First agenda) represented an unexpected break with the prevailing policy consensus of economic integration.

Despite PM Johnson’s promise to ‘get Brexit done’, and the victory of Mr Biden over Mr Trump in 2020 on commitments to return US politics to normal, various events this week – from London and Geneva to Singapore and Washington – show that these remain ongoing political processes. And these dynamics have been further complicated by the regime change in globalisation crystallised by the Western-led response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Taking back control?

Brexit negotiations since 2016 have been largely about political symbols (and internal Tory party politics) rather than about delivering better outcomes. This has been seen again over the week, with the introduction of a Bill to unilaterally override aspects of the Northern Ireland Protocol (to which the DUP in Northern Ireland and some on the Tory Party right objected).

This Bill will likely not pass, will put relations with the EU into the deep freeze (legal action has already been commenced), and does not address the real issues – most Northern Ireland politicians and business leaders want the Protocol to remain, with some practical modifications.

Much of this is performative politics. It is increasingly apparent that the hard Brexit deal is imposing economic costs: the UK’s trade with the EU has been sluggish (and fewer firms are trading); UK inflation is among the highest in advanced economies (partly on higher import costs, labour shortages); and UK GDP growth has been slow (this week, the OECD forecast UK GDP growth for 2023 will be the second lowest in the G20, only ahead of Russia).

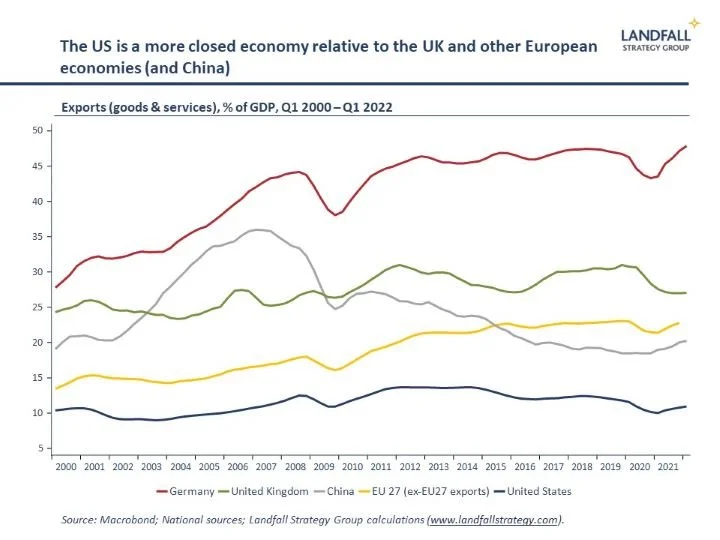

This was predictable (and predicted). Some of these costs could have been avoided had Brexit been managed better. But the emerging global environment makes a successful Brexit challenging. Indeed, the timing for exiting the EU was almost exactly wrong: a highly open, medium-sized economy removing itself from its largest market just as a fragmenting global economy began to manifest.

Brexit-led Global Britain may have had a better shot in the 1990s, when multilateralism was in vogue and hyper-globalisation kicking off. But we are no longer in this world. Indeed, the WTO Ministerial meetings in Geneva this week show the difficulties in delivering meaningful multilateral progress. The action is in bilateral and regional trade deals, where national economic scale matters.

It is difficult to see how Brexit can deliver in the emerging global economic and political context. Applying for CPTPP membership, and signing trade deals with Australia and New Zealand, are good things to do – but they are not a substitute for EU membership in a fragmenting global economy with big power politics. The status quo is not a stable equilibrium: the UK needs friends that are close to home.

And of course, Brexit raises a series of constitutional issues – from Northern Ireland to Scotland. Coincidentally, the campaign for a second Scottish independence referendum was launched this week (see this Scottish Government paper, which references my analysis).

My assessment is that we are at the low water mark of economic/political engagement between the UK and the EU. Over time, and with a new government, there will be pressure for improvement of relations. Indeed, I think it likely that over the next decade or so, the UK will seek to negotiate a partial reversal of the hard Brexit deal. Although returning to full EU membership is unlikely, there will likely be space for some relationship that includes market access. This would be positive for the EU as well.

America First redux

In contrast, the Trump Administration looks increasingly to have represented a turning point in US economic engagement with the world. President Trump withdrew from the TPP negotiations on his first day in office, and subsequently imposed tariffs and other trade/investment sanctions on economies from China to Canada, Japan, and the EU (among others). This was motivated by a desire to reduce the US trade deficit, as well as by his sense that the US was being ripped off by the rest of the world.

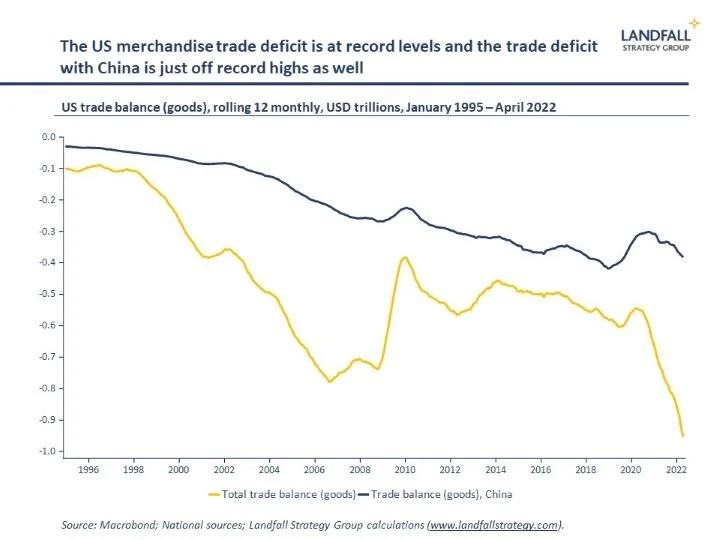

On its own terms, these policies have been unsuccessful – the US trade deficit has expanded, imports from China have increased, and China has breached the deals signed. But it has changed the strategic policy approach of the US. This America First agenda drew a line under the economic engagement approach of previous Administrations (which was shaky anyway); and introduced a much more hawkish approach on China.

And despite the clear differences in tone of the Biden Administration, there has been a high level of policy consistency on international economic/trade issues and on China policy. Indeed, there is broad bipartisan consensus on many of these issues.

Although there has been recent talk of lifting some of the Trump-era tariffs in order to reduce inflationary pressures, this does not detract from the bigger picture of a more inwardly-focused economic policy. There are limits to friend-shoring.

The Biden Administration is not pushing on trade liberalisation or economic engagement, is not progressing WTO reform, and is focused on reshoring economic activity. Legislation is being debated in Congress this week to make it harder for US firm to invest in China.

This means that US engagement in the Indo-Pacific is biased towards security policy rather than economic engagement. US military statements at the Shangri La Dialogue in Singapore last week are more consequential than various US economic engagement initiatives (although note this NYT piece by James Crabtree on US military engagement in Asia).

And if a Republican Presidential candidate wins in 2024 – as currently looks likely – this America First bias in international economic policy is likely to become more pronounced.

In a sense, the US is becoming more like China: focusing on building up domestic capabilities (technology, energy, manufacturing) and reducing exposures. Although there will be selective US economic engagement with friends and allies, general engagement through the WTO or broad trade deals is unlikely. The US has turned, and will become a less open economy over time.

2022 > 2016

2022 is a powerful global turning point – or Zeitenwende to use Chancellor Scholz’s phrasing – reframing events of 2016.

The Western response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine represents a rupture in the global economic system, crystallising stresses and tensions that had been building for several years. A more fragmented global economic system is emerging, with trade and investment flows increasingly shaped by political values and geography.

These dynamics have reinforced the America First agenda, and will lead to an enduring change in US international engagement. In contrast, this emerging model of globalisation weakens the Global Britain model defined by hard Brexit. I am less persuaded that the UK experienced a lasting turning point in 2016; a rapprochement with the EU is likely over time. Geography matters, as I discussed last week. And large economies like the US have more options on decoupling than open economies like the UK.

The economic aftershocks from the Russian invasion of Ukraine will profoundly reshape the global economic and political system, from the UK and Europe to the US and beyond.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly in your inbox, you can subscribe by clicking on the button below:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

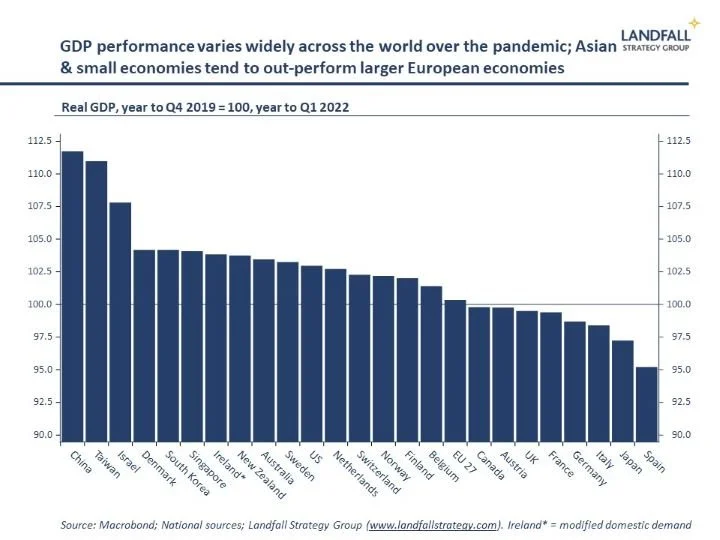

All advanced economies have now reported GDP for Q1 2022. Looking across the full pandemic period since Q4 2019, there is broad variation in performance. Many economies in Asia have performed strongly (Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore), although the ongoing lockdowns in China and Hong Kong will constrain their future performance. Small advanced economies around the world have done well. The bottom of the table is dominated by large European countries.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling