Much ado about everything

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

‘When sorrows come, they come not single spies but in battalions’, Claudius in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Act IV, Scene V)

An eventful week of international meetings in Europe demonstrates the scale and scope of the challenges facing decision-makers around the world. From the G7 meetings in the Bavarian Alps, to the NATO Summit in Madrid, and the ECB conference in Portugal, policy-makers have a full and complicated agenda.

Three things struck me from this week’s discussions: the multiple, intersecting economic and political challenges that governments are dealing with; the global reach of events in Europe, and the strengthening coherence of the West (for now); and the rapid adaptation of countries and institutions to a disruptively changing world.

Polycrisis

The G7 and NATO meetings were dominated by the response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But there are also a broader set of economic and political challenges, which policy-makers are struggling to address.

The G7 again communicated full-throated support for Ukraine and condemnation of Russia – supported by further sanctions on Russia (on technology imports, gold exports). But G7 leaders were also grappling for ways in which to alleviate the economic spillovers from the ongoing conflict, notably on the cost of living.

A price cap was proposed on Russian oil exports, using Western control over shipping and insurance to deliver compliance. But it is not clear that this idea has legs. And actions to increase global energy supply to control energy prices were promoted, even though these actions were not fully consistent with commitments to reduce emissions. Indeed, coal plants are being fired up in several European countries to reduce the risks of energy shortages.

There is a difficult political balancing act between sanctioning Russia, delivering good domestic outcomes (such as inflation), and achieving objectives such as emissions reductions.

Mr Putin is likely counting on Western resolve to waver due to the economic costs. Policy fatigue is not yet evident, but recent polling suggests that a significant share in the EU favour an end to the conflict. Indeed, many G7 leaders face political challenges due in part to cost of living issues: PM Johnson just survived a vote of no confidence; President Biden is polling poorly; President Macron lost his Parliamentary majority; and PM Draghi’s coalition is fraying.

At the best of times, G7 meetings struggle to develop consensus around ambitious actions. And these are clearly not the best of times. The G7 is performing much better than when Mr Trump prevented anything from happening, but there is a sense of muddling through in response to multiple, intersecting crises under conditions of deep uncertainty.

‘A polycrisis is not just a situation where you face multiple crises. It is a situation… where the whole is even more dangerous than the sum of the parts’, Adam Tooze.

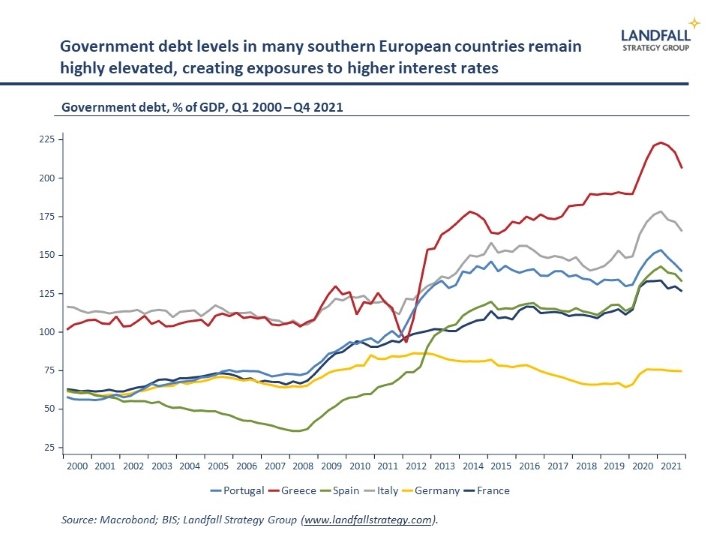

Responding to inflation is another dimension of this polycrisis. The ECB, which held a conference in Portugal this week, is juggling surging inflation (importantly due to higher energy prices), a weakening Eurozone economy, as well as high debt levels in key member states.

This is further complicated by uncertainty about whether a hawkish approach is required to prevent a higher inflation rate regime emerging (a risk identified in this week’s annual report from the BIS): Ms Lagarde and her peers sounded a tougher note this week. The stakes are high.

Overall, we should position for substantial economic and political turbulence. There are no easy policy answers, substantial uncertainty, and conflicting political and economic imperatives. This means a lot of policy experimentation in the transition to a new policy regime. Small advanced economies, with distinguished policy innovation records, are likely to lead this process.

From Europe to the world

Europe is ground zero for the war, exposure to high energy prices, and so on. But these issues have global reach: the Russian invasion of Ukraine has crystallised structural change in the global economic and political system. We are seeing a shift to a more fragmented global system, with trade and investment flows increasingly shaped by political considerations.

A key locus of these aftershocks will be in Asia, particularly in terms of relations between China and the West. This broader focus was evident in discussions at NATO and the G7. In an unprecedented move, the leaders of South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand joined the NATO Summit. The invitation of these countries reflects the broad challenge to the rules-based international system.

Indeed, China was explicitly mentioned in NATO’s new Strategic Concept. It noted that China was a source of ‘systemic challenges’ to the Euro-Atlantic space: China’s ‘stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values’.

The G7 communique also considered relations with China, on issues from human rights to international law. A $600 billion ‘Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment’ was (re-) announced, a de facto rival to China’s BRI (which has been struggling recently). And just prior to the G7 meetings, a ‘Partners in the Blue Pacific’ initiative was announced – involving the US, the UK, Japan, Australia and New Zealand – in response to China’s greater assertiveness in the Pacific.

Taken together, this suggests a coherent, strengthening Western response to various challenges to the rules-based system. And support for NATO and the US remains generally high across advanced economies.

This shouldn’t be taken for granted. The clock is likely ticking on constructive US engagement in institutions such as the G7 and NATO; a future ‘America First’ President may be less engaged. This matters because the US remains central to the Western alliance: the US has provided the majority of military and financial support to Ukraine for example.

Present at the creation?

These meetings also provide a sense of the emerging shape of the global system. Countries and institutions are adapting to a disruptively changing world in ways that would not have seemed likely several months ago. There has been a surprising amount of policy and institutional innovation.

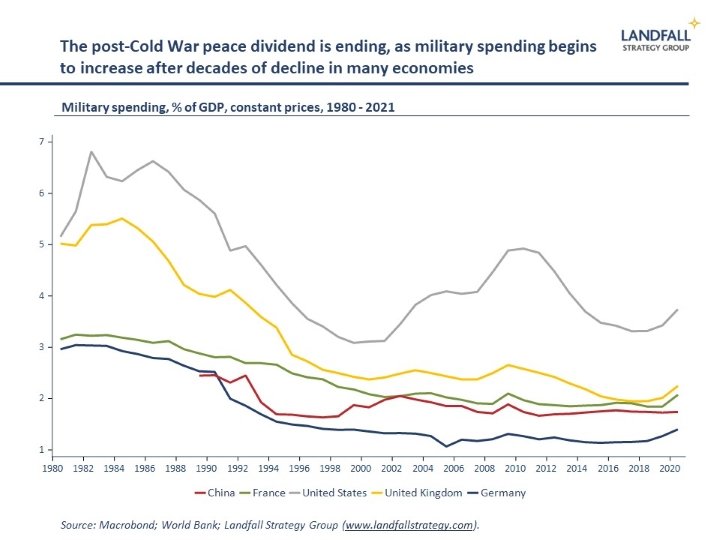

Increased clarity of purpose was evident at the NATO Summit; it has gone from ‘brain dead’ in Mr Macron’s 2019 framing to an increasingly forceful coalition, largely due to Russia’s behaviour. Decisions were taken to significantly increase NATO’s forward presence in eastern Europe; a new Strategic Concept was agreed; and Sweden and Finland were admitted as members. And numerous NATO members committed to significantly increase military spending.

Many countries (Sweden, Finland, Germany, New Zealand, and others) have been re-assessing their external positioning over the past months, and are making different choices. Complacency has reduced and there is a much greater degree of seriousness about the world that we are in. And, of course, China and others are responding to these changed behaviours.

This new global economic and political regime will require further institutional innovation. New institutions often emerge after crises – from the UN, IMF, and GATT after WWII, to the G6 (now G7) after the Bretton Woods collapse. Expect institutional flux as old institutions reinvent themselves (the WTO has surprised positively) and as new institutions emerge.

These issues are too important to be left to the big powers, as the patchy record of the G20 shows. Small states can add significant value, as the Baltics and Finland have in shaping the EU and NATO debate on Russia; and as small economies in Asia did with respect to the CPTPP. And the EU/New Zealand FTA agreed yesterday was pathbreaking, integrating trade liberalisation and sustainability.

Big powers have no monopoly on wisdom in institutional and policy design, particularly in times of full-spectrum disruptive change.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

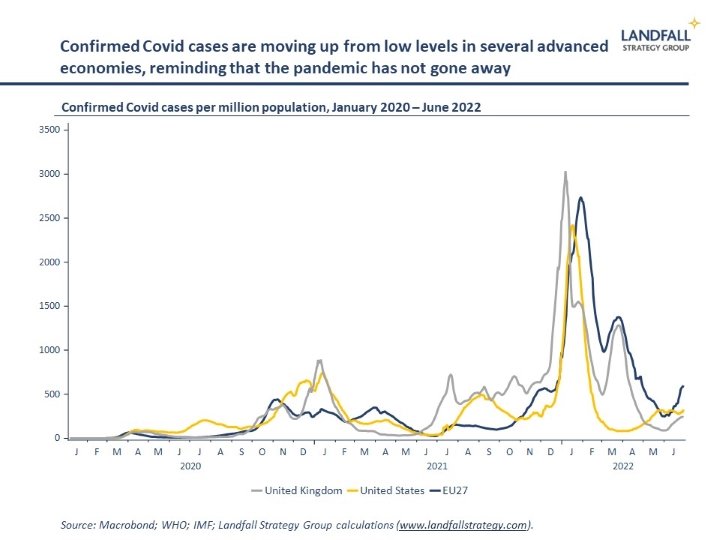

Chart of the week

Covid, another element of the global polycrisis, has not gone away. Daily cases have begun to move up again in Europe, as well as parts of Asia, although death rates remain relatively low. In the US, the UK, and the EU, confirmed cases are higher than this time last year despite much lower rates of testing. Almost all restrictions have been removed, new variants are spreading, and there is substantial reluctance across advanced economies to impose meaningful restrictions again. Ongoing case growth is likely.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling