Economic war of attrition

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Over four months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, what was expected by the Russians (and multiple foreign intelligence services) to be a lightning raid has turned into a grinding war of attrition.

Assessments vary in terms of how momentum on the battlefield is likely to change over time (see these pieces by military academic Lawrence Freedman and the Economist). Some point to Russia’s superiority in raw power (ammunition, weaponry, soldiers) as a growing advantage over time relative to Ukraine, which has been taking heavy losses. In contrast, others point to the arrival of sophisticated Western military equipment and the morale and capacity constraints facing Russia and suggest that momentum is with Ukraine.

First world economic war

But the outlook for the war between Russia and Ukraine is as much about economics as it is battlefield assessments: I have previously termed this ‘the first world economic war’. There is a war of attrition in economic terms also, as countries weigh rising economic costs against desired strategic outcomes.

Russia’s headline economic numbers look better than initially expected. The rouble has strengthened above pre-invasion levels, for example, on capital controls as well as the stronger trade balance: export income is up, imports are down. In a recent speech at the sparsely attended St Petersburg International Economic Forum, Mr Putin talked a big (and delusional) game about the resilience of the Russian economy.

But the Russian economy is expected to contract substantially this year, there is a substantial brain drain underway, Russia can no longer access leading technology from offshore, and commercial planes will not be able to keep flying for much longer. There are reports of cannibalising washing machines for electronics to insert into military equipment, and some military factories are stopping production.

Russia can export commodities, but structurally its economy is in deep trouble. This economic hollowing out creates meaningful capability constraints, and means that time is not on Russia’s side. Indeed, Russia has now been forced to begin to move its economy onto a war footing.

For Ukraine, the near-term economic costs are very large. The IMF projects a contraction of over a third in Ukraine’s GDP this year. The Ukraine central bank is struggling to finance the costs of the war. And a donor conference in Switzerland this week heard estimates of a reconstruction bill of $750 billion (almost 4x pre-invasion GDP). Housing, infrastructure, and productive assets are being progressively destroyed.

Ukraine is reliant on both military and financial support from its allies, particularly in North America and Europe. Russia can only ‘win’ by inflicting economic pain on the West, pressuring it to reduce support for Ukraine and to push for a peace deal. And so the outlook is importantly dependent on whether the economic costs bind more deeply and quickly in the West or Russia.

Is economics > politics?

Mr Putin has (wrongly) claimed that the conflict and sanctions are having a bigger economic impact on the West than on Russia. But although the costs imposed on Russia will be much more substantial and lasting, there are also significant near-term costs on Western economies.

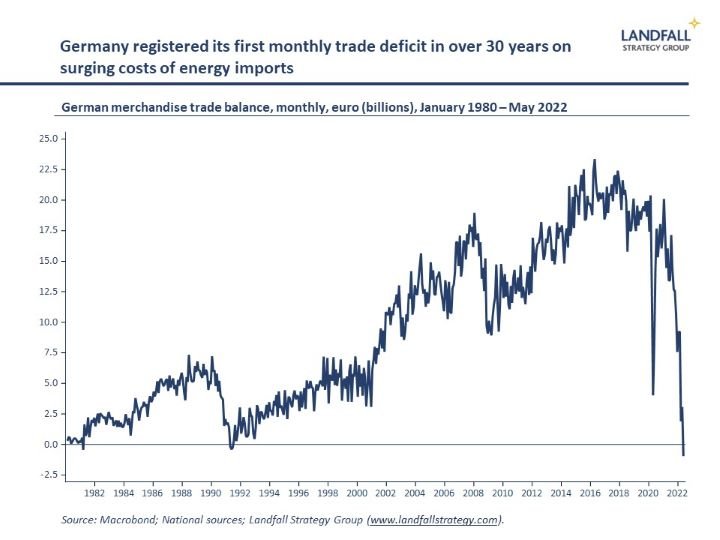

One marker of these macro pressures was this week’s data that showed Germany’s first trade deficit in >30 years: exports are at record highs, but this was offset by surging costs of energy imports. And over time, higher input costs will reduce German export competitiveness. This geopolitical conflict is doing significant damage to the German economic model.

Across Europe, energy prices have spiked higher – largely as a consequence of higher Russian gas prices. Higher energy prices, as well as the potential for higher interest rates, are creating a drag on economic activity – recessions in Europe are seen as increasingly possible.

And high energy prices will create political difficulties. Governments are acting to offset some of the costs, and are developing alternative energy supplies. But even so, political unrest is likely: the gilets jaunes protests in France from 2018 provide an example. And across Europe, industrial action is on the rise in response to cost of living pressures.

So far, Western governments have been coherent and aggressive in imposing sanctions on Russia and providing military and financial support to Ukraine – and with broad public support. But sustained steeply higher energy costs, the potential for energy rationing, and economic recession, will test public support and political resolve. Opinion polling in Europe suggests some economic reservations in support for Ukraine. These political risks create a race against time to support Ukraine.

‘All politics is local’, Tip O’Neill

A key country to watch in this regard is the US. Although less directly exposed to Russian energy than Europe, economic costs are being imposed on the US – and President Biden’s poor polling is partly due to cost of living pressures. So far, there are no signs of slackening support for Ukraine by the Biden Administration. But the economic costs, and the potential for a change in the centre of gravity in US policy after the November mid-term elections, create risks.

This matters because the US is – by far – the largest military and financial supporter of Ukraine. On these numbers, European strategic autonomy is a way off.

The question is whether this economic war of attrition will weaken Western attitudes towards sanctions on Russia and support for Ukraine. Can the West or Russia better absorb the economic costs that are being imposed? Can Western countries sustain sufficient political resolve on Ukraine in the face of mounting economic costs?

This is a major test for the West. And for smaller states that are exposed to big power politics (from Eastern Europe to Taiwan), the demonstrated strength of this commitment to defending the rules-based system is of existential importance.

Nowhere to hide

The emergence of the economic war of attrition also has implications for the nature of country and firm exposures. The immediate economic exposures to the conflict related primarily to countries and firms that had major direct exposures to Russia. However, economic wars of attrition lead to much more generalised costs being imposed.

High energy prices, slowing economic activity, and so on, have broad effects on firms and countries irrespective of their direct exposure to Russia/Ukraine. The dampening effect on economies around the world – with a rising risk of recession across European economies – means that even domestically-focused firms face costs.

Indeed, this is the historical experience with economic sanctions, particularly when deployed at scale against an economy that has material linkages with the global economy (note this recent piece by Nicholas Mulder, an historian of economic sanctions). Sanctions are not a precision scalpel, and have boomerang effects.

Small economies can stay out of the way of some conflicts (like the US/China trade wars), but these attritional economic conflicts have a global economic impact that is hard to avoid.

These realities should be borne in mind by countries and firms in positioning for future economic conflict. Beyond Russia, the most likely geopolitical flashpoint is with China – a much more material, central part of the global economy than Russia.

Of course, countries and firms with direct exposures to China should be particularly deliberate about managing these exposures. But simply reducing China-related exposure is not enough given what would be very broad-based economic costs in the event of meaningful sanctions – as with Russia, the indirect exposures will be very significant. Economic fragmentation and decoupling will be a costly process, reaching far into domestic economies.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

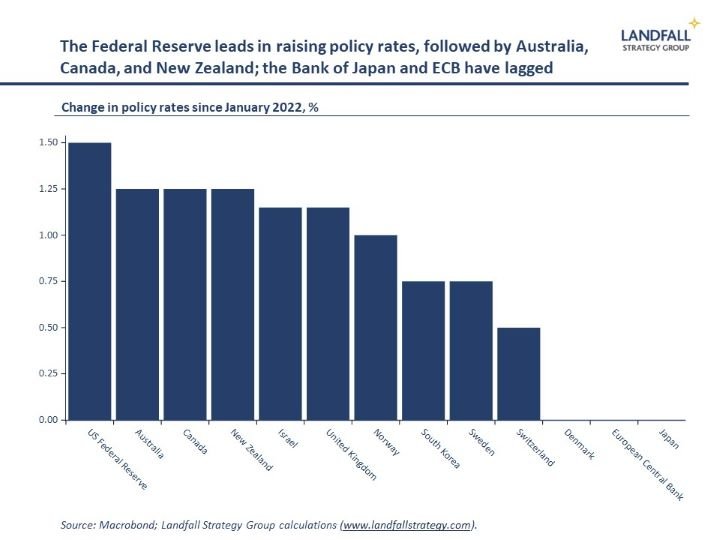

Central banks continue to raise policy rates in response to surging inflation. This week, Australia, Sweden, and Israel lifted rates; Switzerland surprised by lifting by 50bp a couple of weeks ago; and the ECB is set to move later this month. Since the start of the year, the Fed has lifted the policy rates by 150bp, with the RBA, RBNZ, and Bank of Canada lifting by 125bp, and with more to come. In contrast, the ECB and Bank of Japan have not yet moved – which partly explains why the euro and JPY have depreciated significantly this year.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling