The politics of inflation

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

There has been much recent economic and market commentary on the return of inflation, with a range of supporting evidence.

In addition to surprises in US CPI data, commodity prices (energy, metals, lumber) have spiked up, international air and shipping costs have increased sharply as supply chains come under pressure, and there are wage pressures in parts of many labour markets.

Markets are pricing in higher inflation and a central bank policy response. Government bond rates have been increasing, and equity markets have wobbled recently – despite the robust global economic recovery underway.

Much ado about…

But my assessment is that the scale of near-term inflation concerns has been exaggerated. Inflation will be higher, but a sustained rise in inflation above the target range for more than several months is unlikely. The price pressures reflect base effects, as well as costs associated with reopening economies from a virtual standing position.

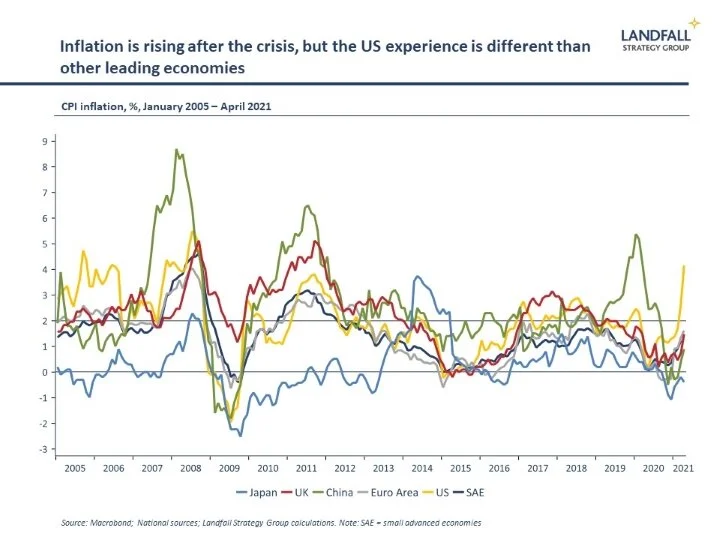

The inflation debate is also largely motivated by the US experience, where inflation was 4.2% for the year to March (April data, expected to be strong again, is out later today). But inflation is less pronounced elsewhere: CPI inflation is 0.9% in China, 1.6% in the eurozone, and across the small advanced economies – deeply exposed to global dynamics – it is 1.2%. Core CPI inflation rates are more modest again.

Central banks, from the Federal Reserve and the ECB to the RBNZ, argue that the observed inflationary pressures are transitory, and will weaken over the course of the next year or so.

It’s political

But despite this positive near-term inflation outlook, structural inflation risks are rising – but primarily for political not economic reasons.

Milton Friedman claimed that ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’. But this deterministic relationship between monetary variables and inflation has not been sustained in the data.

It is better to see inflation as ‘always and everywhere a political phenomenon’. The nature of the prevailing economic policy regime sets the limits for monetary policy. It was US political decisions that set the stage for US inflation from the late 1960s (federal spending on both the Vietnam War and the Great Society, the break with the gold standard, and political pressure on the Fed). And the changing political appetite from around 1980 allowed Paul Volcker to raise rates to 20% to kill inflation.

More broadly, the global economic policy regime change from the late 1980s supported the establishment of independent central banks targeting price stability – led by countries such as New Zealand and Sweden. The Great Moderation followed. And even in the post-GFC period, with the introduction of QE and negative policy rates in some jurisdictions, inflation targets have remained in place (even if seldom hit).

But a policy regime change is underway, with a shift from policy rules to policy discretion, which will shape the inflation outlook. There are two key drivers.

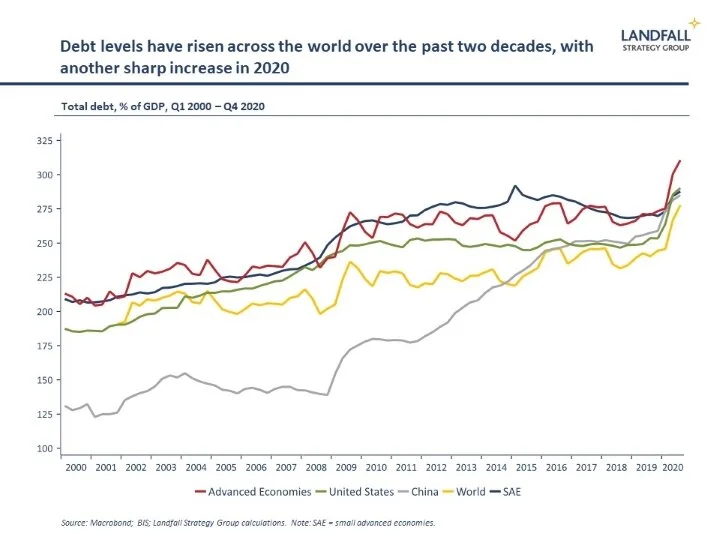

First, the fiscal policy regime change that is underway has direct implications for monetary policy. There has been a marked shift in the consensus on appropriate levels of public debt, and fiscal policy is likely to remain expansionary for some time. Over time, this will create inflationary pressures.

In addition, the structurally higher levels of public debt after the Covid shock, combined with high levels of corporate and household debt, makes raising policy rates difficult – at least without causing economic and fiscal turbulence. As in previous periods, monetary policy will be increasingly subordinated to fiscal policy (‘fiscal dominance’).

Second, this is happening in a context of greater political pressure on central banks. As central bank decision-making has had increasingly apparent impacts on asset prices and the wealth distribution, monetary policy has become increasingly subject to political oversight.

As one example, the mandate of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, a global leader 30 years ago in central bank independence in pursuit of price stability, has been recently broadened to include language on the real economy (and more recently again on house prices).

On the margin, this makes it less likely that policy rates will be increased aggressively. And also that central banks will use other tools e.g. macro-prudential policy, to pursue their mandate rather than interest rates.

Short-term v medium-term

Taken together, this means that central banks will be more likely to keep rates lower for longer, to respond more slowly to inflationary signals, and to be subordinate to fiscal policy imperatives. This won’t be a return to the inflation experience of the 1970s, but there will likely be a higher tolerance for inflation.

So inflation is more of a medium-term risk over this decade rather than over the next 1-2 years. This is the opposite view to those that argue that high inflation is more of a concern in the short-term than in the longer-term when structural forces like technology and global demographics will reduce price pressures.

Indeed, I hold this view despite my optimism about a productivity renaissance, driven by accelerated investment in technology and new business models.

In sum, inflation is about politics as much as economics. The economic data provides a useful perspective on the inflation outlook, but even more important are the political dynamics that shape monetary policy. Inflation will be driven by policy choices: a policy regime change is likely to lead over time to a regime change in outcomes as well.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss this analysis and its implications. I am also available for presentations and discussions on other global economic and political dynamics, and the implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Do let me know if your organisation is interested in arranging a discussion.

Chart of the week

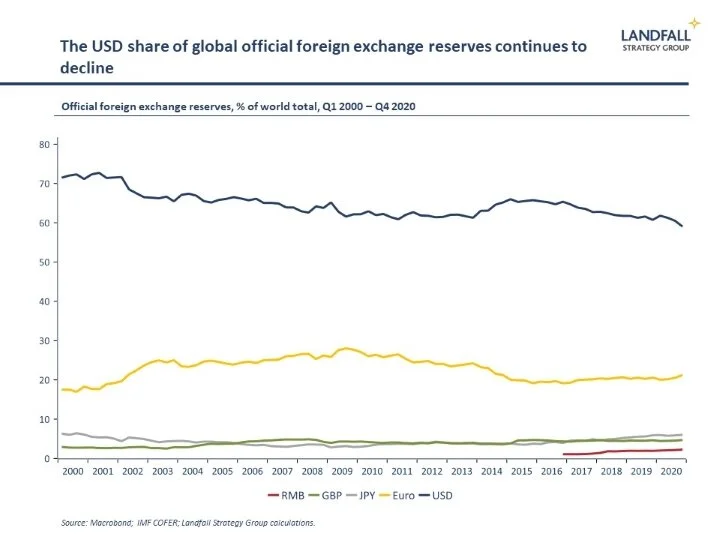

IMF data just out shows that the USD fell to a 59% share of official foreign exchange reserves worldwide, down from a 71% share in 2000. The euro has a 21% share, with small allocations to other currencies. Although there have been many predictions of the demise of the US as reserve currency, with another round of commentary after this data release, this seems a way off (short of some major political or economic shock). In the meantime, reserve currency status confers benefits on the US – although it’s not the exorbitant privilege sometimes claimed (as I wrote in this McKinsey Global Institute report a decade ago).

Other writing

I had an op-ed published last week in Singapore’s Straits Times, with reflections on the small advanced economy experience through Covid – and the outlook and policy priorities for small economies, including Singapore. The piece is available here.

Around the world in small economies

The New Zealand Government delivered its Budget last week, with a better economic and fiscal outlook than the previous forecast. Net debt is forecast to peak at 48% in 2023 before gradually declining, largely due to GDP growth that will trend at 3-4% for much of the forecast period.

Singapore’s ‘Emerging Stronger Taskforce’ report has just been released. This Taskforce was assembled to make recommendations on Singapore’s post-Covid economic strategy, identifying new opportunities for Singapore.

Switzerland has unilaterally ended the cooperation talks with the EU on reaching a new framework agreement to replace the scores of individual agreements. And as of this week, medical technology exports from Switzerland to the EU will be treated as third party exports – subject to additional restrictions.

Negative interest rates are increasingly rare in small economies; only Switzerland now has negative rates, after the Netherlands moved into positive territory. At the end of 2020, there were eight small advanced economies with negative rates. And the Reserve Bank of New Zealand held policy rates this week but projected increasing policy rates from next year as the economy recovers.

A Dutch court ruled on Wednesday that Shell was required to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030 relative to 2019 after a case was brought by environmental activists. This is certain to be appealed, but courts are increasingly active in this space. In 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court ruled that the Dutch Government had to speed up its emissions reduction efforts.

Costa Rica has become the OECD’s 38th member, after a six year accession programme was completed this week.

Being a relatively recent arrival to Europe, I decided to throw myself into Eurovision – hosted just down the road in Rotterdam. Italy won, but for my money the best songs came from small states: Switzerland, Lithuania, and Iceland (Bulgaria, Finland, and Greece were also good). The UK and Germany got the last two places; the Germans justifiably, the UK less so.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling