Stormy weather, changing climate

The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook, released on Tuesday, made for grim reading. GDP growth was marked down again, inflation is expected to be more persistent, and financial stability risks are elevated.

As the IMF Chief Economist noted:

The 2023 slowdown will be broad-based, with countries accounting for about one-third of the global economy poised to contract this year or next. The three largest economies, the United States, China, and the euro area will continue to stall. Overall, this year’s shocks will re-open economic wounds that were only partially healed post-pandemic. In short, the worst is yet to come and, for many people, 2023 will feel like a recession.

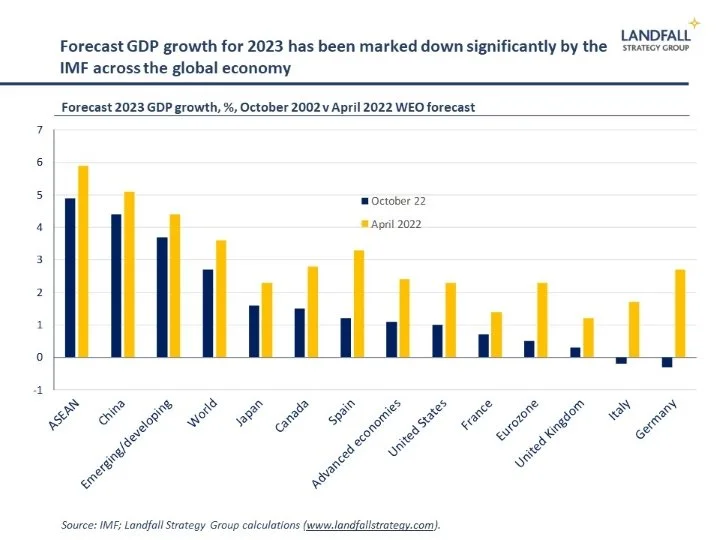

Forecast GDP growth for 2023 is 1.0% in the US, 0.5% in the Eurozone, 4.4% in China, and 2.7% globally. And the IMF estimate a 25% likelihood that world GDP growth comes in below 2%, growth rates not seen over the past 40 years outside the global financial crisis and the pandemic.

GDP growth rates were marked down significantly from the IMF’s last full set of forecasts in April, and also from the interim forecasts in July. The US was marked down by 1.3% since April, the eurozone by 1.8%, and China by 0.7%. World GDP growth for 2023 was downgraded from 3.6% to 2.7%.

This weak performance is due to a combination of factors: the legacy of the pandemic, the spillovers of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Covid lockdowns and a property slowdown in China, a surging USD, and so on.

It is possible that we have reached peak gloom. After a sustained run of negative economic surprises, we may be due some positive surprises. But consensus economic forecasts are negative, and markets remain decidedly downbeat.

Beyond the headline economic forecasts, the IMF data also capture structural changes underway in the global economic and political system.

Convergence, interrupted

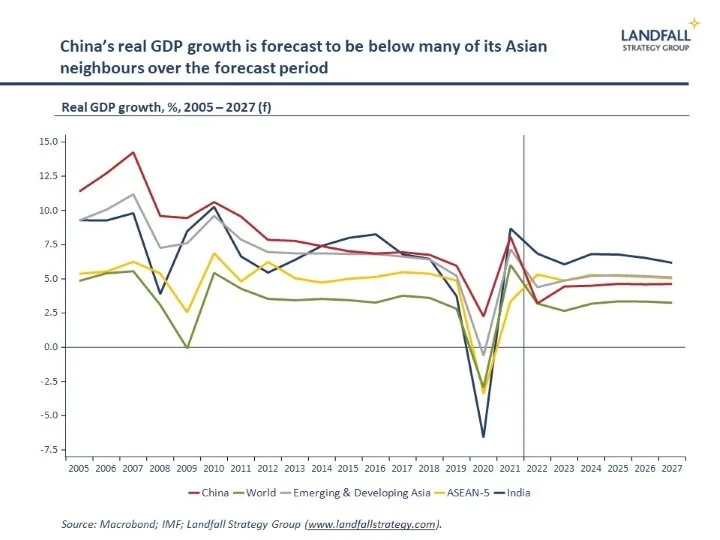

These changing economic outlooks will have an impact on the global economic hierarchy. China has converged rapidly towards the global income frontier on strong GDP growth rates over the past few decades. But China’s economy is slowing sharply, on short-term headwinds (Covid lockdowns) as well as structural weaknesses and contradictions in its growth model.

The IMF forecast 3.2% growth in China in 2022, and 4.4% in 2023, well below its pre-pandemic levels. And China’s economy is expected to grow less rapidly than India, the ASEAN-5 economies, and emerging Asia over the next several years. This is the first time that this has happened in a few decades. China’s shrinking working age population will also create headwinds for the Chinese economy.

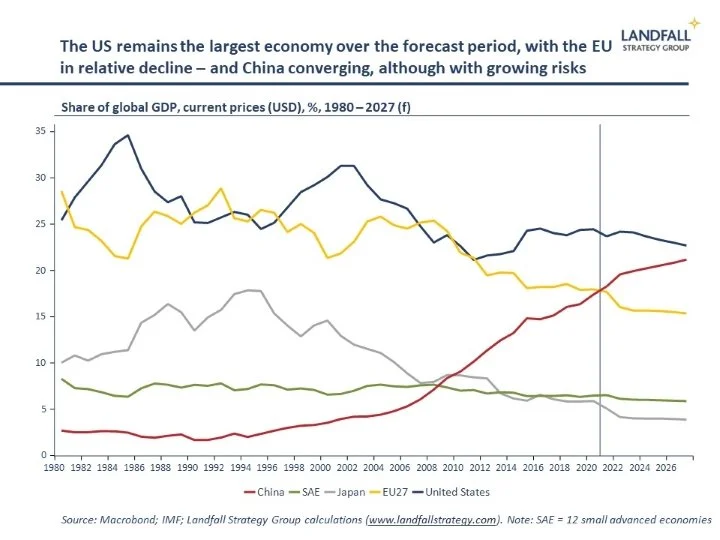

This creates big challenges as Mr Xi takes on a third term at the Party meetings later this month. China is still the dominant market in Asia, but its growth rates are fading. Although the IMF forecast that China’s share of global GDP will converge towards that of the US, there are growing questions about whether China’s GDP will overtake the US – particularly as an agenda of reform and opening up is unlikely under the current leadership.

More broadly, emerging markets are facing headwinds; from higher food and energy prices, to a surging USD and the relocation of supply chains. The growth models of many emerging markets are challenged, and the pace of income convergence has slowed.

Elsewhere, a structural gap is widening between the EU and the US. The EU’s share of global GDP is weakening sharply on slower growth and a rapidly depreciating euro; whereas the US share is more stable. This reflects the challenges to the European growth model. Although economic doom mongering about Europe is often exaggerated, changes need to be made to strengthen Europe’s economic potential (note this recent McKinsey analysis).

These economic relativities matter for the balance of geopolitical power. The US remains the dominant global economic and financial centre, which enables it to project political power. Similarly, the trajectory of China’s economy will shape its geopolitical heft.

Balance of power

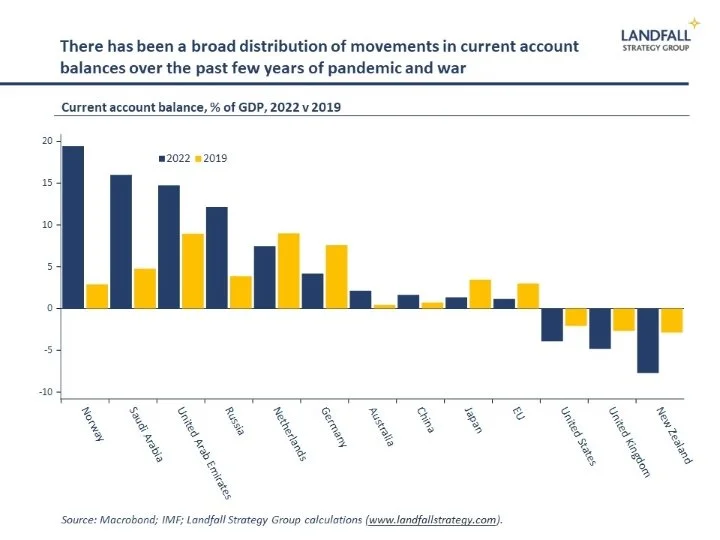

The current account balance is another useful measure of the global reordering. After a decade of compression of current account balances around the world, the pressures of pandemic and war have led to larger current account deficits and surpluses.

This creates stress across the global financial system: larger cross-border capital flows are required to finance larger current account deficits, which can be destabilising.

Changing current account balances also provide a sense of the impact of global shocks on national growth models. Current account balances have shifted markedly between pre-Covid 2019 and 2022, on the back of the pandemic (e.g. tourism) and war (e.g. energy costs).

Many European countries have had markedly weakened current account balances on higher energy prices. This is also challenging the competitiveness of exports from some European countries, such as Germany and the Netherlands. In contrast, the US has been more resilient to rising energy prices due to its energy independence – but a strong USD and a slowing global economy drag on exports.

Energy exporters have done well: the current account balance is 19% of GDP in Norway, 16% in Saudi Arabia, and 15% in the UAE. And Russia’s current account surplus has (temporarily) strengthened. Greater energy independence by oil and gas importers (e.g. renewables) will change this profile over time. In the meantime, surging current account surpluses provide greater political space – for example, note Saudi Arabia’s more assertive actions at OPEC.

Elsewhere, rapidly widening current account deficits provide an indication of structural challenge to growth models. In the UK, the current account deficit has weakened to ~5% of GDP – on energy imports, Brexit, and so on – which created some context for the recent sell-off in the GBP and UK gilts. And New Zealand’s ~8% of GDP current account deficit has contributed to the NZD’s weak performance (down ~20% against the USD this year) despite aggressive policy rate increases.

Small economy resilience

The growing frictions on globalisation and geopolitical rivalry, which are leading to a fragmenting global economy, are commonly argued to create particular challenges for small economies – because small economies are deeply exposed to the global economy (their export/GDP shares are commonly >2x those of large economies).

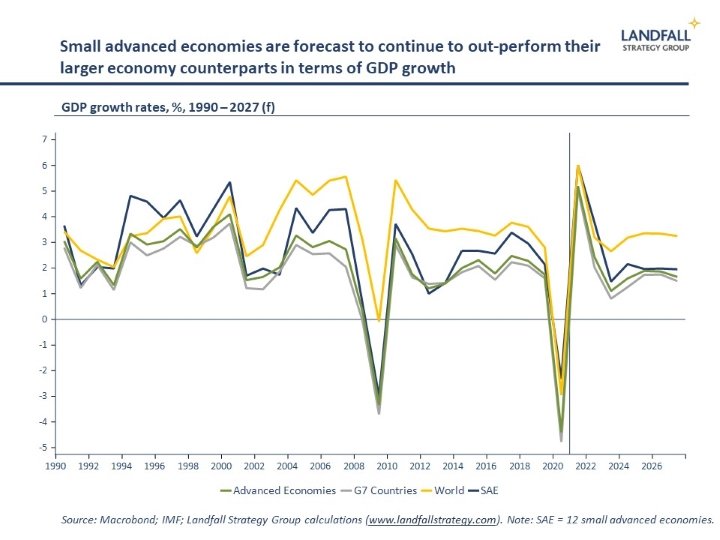

After consistent out-performance over the past few decades of hyper-globalisation and the Great Moderation, the argument is that the changing external environment may compromise the small economy growth model.

But small advanced economies have out-performed through the pandemic. And the IMF forecasts suggest an ongoing performance edge over the G7 economies over the next several years; and for European small advanced economies over the large European economies of France, Germany, Italy, and the UK. Small advanced economies have held their share of global GDP stable even as the share of other advanced economies has declined.

The agility and responsiveness of small economies – combined with the competitive imperative to change – are a valuable asset in responding to disruption. Many small advanced economies are working hard to position for a new environment – from Singapore to Ireland, where I presented last week on adapting economic strategy to a new world.

Some investors respond to rising geopolitical risk by prioritising economies with large domestic markets that are less directly exposed to global shocks. But this recent and forecast performance suggests that small advanced economies may continue to be a place to allocate capital. Strong policies and institutions, and responsiveness to external changes, will likely support small economies in navigating global regime change.

This small economy experience provides a positive message: that it is possible to respond to global challenges, and to continue to prosper.

Overall

Beyond the near-term economic and political turbulence, structural changes are underway in the global economic and political environment. The balance of economic power across the world is shifting, which will have implications for geopolitical power. Countries will need to adapt their growth models to new realities, with greater geopolitical competition and frictions on global flows of trade, energy, and capital.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

It’s not strictly speaking a chart, but the record of votes in the UN General Assembly this week rejecting Russia’s illegal annexation of four regions in Ukraine is striking. The resolution passed with 143 votes for, 35 abstentions, and 5 opposed. This was almost exactly the same pattern as for the first resolution condemning Russia in March (141/35/5), showing broad global support for Ukraine despite the costs imposed by the ongoing war. The abstentions were largely from the Global South - parts of Asia (notably China and India), Africa, and Latin America. Russia’s support came from Belarus, Nicaragua, North Korea, and Syria.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

https://davidskilling.substack.com