Return of the state

‘The era of big government is over’, President Clinton, 1996 State of the Union

One of the striking aspects of recent policy across advanced economies has been an expanding role of the state. The massive government support to households and firms to cope with Covid and now the energy crisis, as well as commitments to increased defence spending, provide recent examples.

Small state models of economic policy work better in more benign conditions. The pandemic, war, and strategic geopolitical competition are now generating new policy dynamics. Indeed, global economic and geopolitical regime change have previously led to regime change in the role of the state: the emerging narratives around the Washington Consensus, the flat world, and the end of the Cold War, supported a shrinking of the state from the mid-1990s.

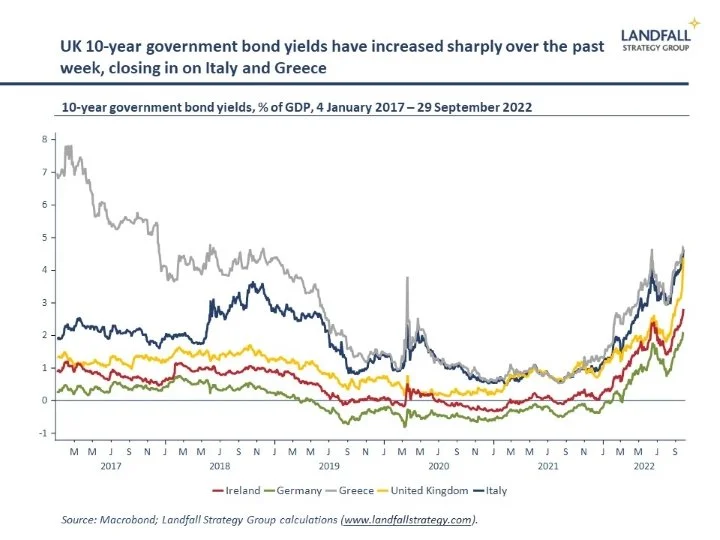

This transition will likely be turbulent. The omnishambles of last week’s UK ‘fiscal statement’ (debt-funded tax cuts on top of substantial fiscal support for energy payments) shows what can go wrong if governments try to mix new (high spending) and old (low tax) regime playbooks. And particularly in the UK context of high inflation, a large external deficit, and deep concerns about policy and institutional credibility.

Shifting centre of fiscal gravity

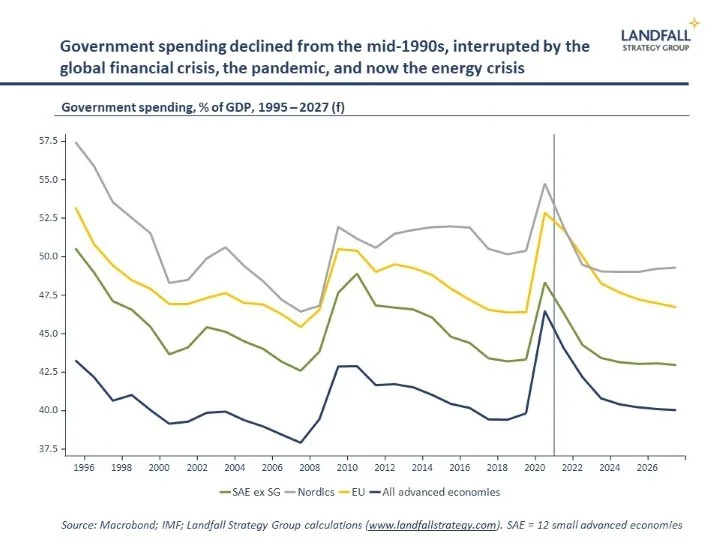

Advanced economies have had generally reducing government spending levels over the past few decades, together with reducing public debt levels – although with variation across countries.

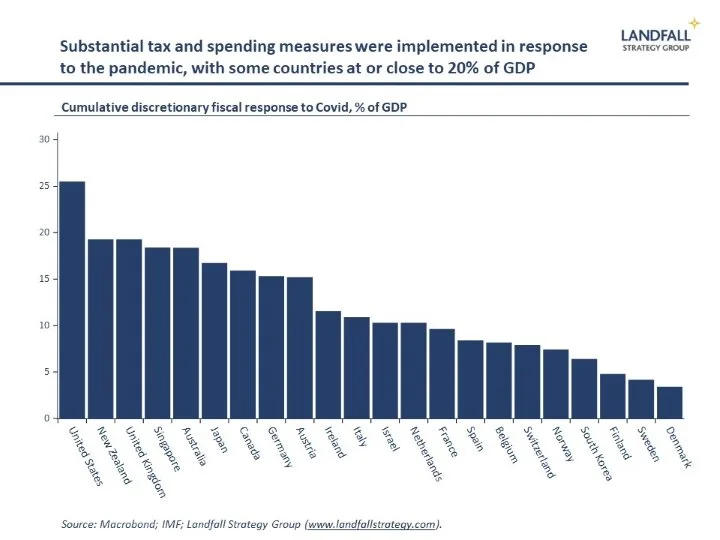

This began to change through the global financial crisis, as growth slowed and stimulus was required. There were some subsequent efforts at fiscal consolidation, supported by low borrowing rates. But spending increased through the pandemic as governments stepped in to provide substantial support to firms and households. In many advanced economies, discretionary fiscal support amounted to over 10% of GDP – with several close to or above 20% of GDP (Singapore, New Zealand, UK, US).

These schemes helped to limit unemployment and supported economic activity. But across advanced economies, gross government debt rose by ~20% of GDP through the pandemic.

And substantial fiscal support is being provided across Europe (and beyond) in response to the current energy crisis. The estimated fiscal cost of commitments made to date in the UK is ~€180 billion (6.5% of GDP) and over 2% of GDP in several other European countries (3.3% in Italy, 2.9% in France, 2.8% in Germany). Last week’s Dutch government budget announced measures to buffer households from rising energy costs (estimated at 2.7% of GDP), as well as a 10% increase in the minimum wage to address cost of living issues.

The depth of the crises over the past several years has led to changes in attitudes to government spending. Governments are under pressure to protect households and firms against major shocks. Higher levels of government spending are likely in areas from public health to social insurance in response to growing public demands. In the US, there is increased spending on measures from industry policy to the partial forgiveness of student loans.

Even in right-wing political parties, there is greater appetite for increased government spending (the Tory Party in the UK is an example on energy support payments). Indeed, my assessment is that the UK government is more likely to increase spending than to reduce spending and cut taxes; a partial reversal of last week’s fiscal announcements is likely.

Although some of these spending measures are intended as temporary, there is frequently a ‘ratchet effect’, in which government spending increases in crises but is difficult to lower subsequently.

And structurally, there will be demand for higher government spending and investment to finance the net zero transition as well as the fiscal costs of population aging. And military spending is likely to increase sharply, with many governments committing to raise spending to at least 2% of GDP. Taken together, government spending as a share of GDP is under upward pressure.

Bond vigilantes no more?

‘I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope, or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody’, James Carville (advisor to President Clinton)

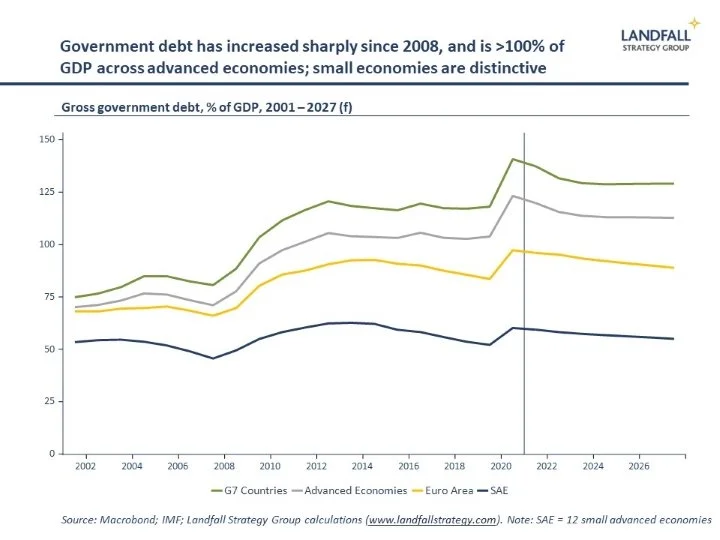

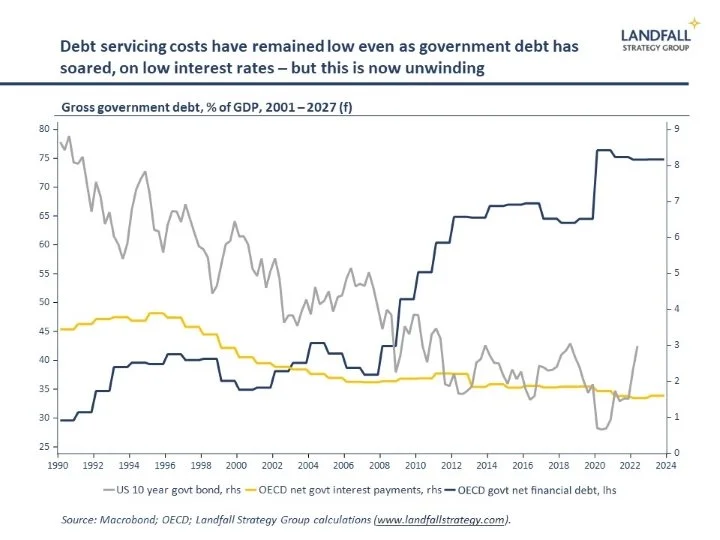

Government spending is no longer constrained to the same extent by a hard government budget constraint. In the very low interest rate environment of the past decade, public debt accumulation has been less of a concern. Government debt levels have increased markedly over the past decade, to over 125% of GDP across the G7. The IMF forecasts government debt to remain at these elevated levels over the next several years (with significant upside risk).

Even short of extreme MMT/Dick Cheney (‘deficits don’t matter’) positions, governments are acting with more freedom of manoeuvre on debt. For example, proposals are being developed to effectively relax the EU’s fiscal rules (the Growth and Stability Pact), when they are re-introduced after being suspended during the pandemic.

Note, however, that the picture is different across small advanced economies: many small economy governments (notably in Northern Europe) have government high spending but are conservative on fiscal balance – in part because they are more exposed to external shocks, and take greater care to manage risks.

Of course, bond vigilantes occasionally reappear – such as in UK gilt markets this week – when there are concerns about the scale of fiscal loosening, the quality of decision-making, and the strength of institutions. The government’s budget constraint has weakened, not disappeared.

Indeed, governments are looking to bolster their revenue-raising ability. The international minimum corporate tax agreement brokered by the OECD was motivated by a desire to increase revenue-raising capacity for larger economies (reducing tax policy competition). Firms and investors should expect increases rather than reductions in corporate tax rates – and increases in wealth taxes are likely.

Implications

The past 30 years of the Great Moderation have supported a declining government spending track, but that is now unwinding. Global stress and disruption combined with changing public expectations are leading to upward pressure on government spending and public debt levels.

Government capability becomes even more important as the size of the state increases, and as policy rules weaken in favour of policy discretion. It does not take much imagination to develop scenarios in which a larger, more activist state generates poor outcomes.

Equally, strong state capability can be a source of national competitive advantage. Many small advanced economies (such as those in Northern Europe), with strong state capability, have high levels of government spending while remaining competitive and productive, with healthy economic and social outcomes.

Indeed, the Dutch, Irish (and French) government budgets over the past week or so, announced spending and tax initiatives to support firms and households facing energy and cost of living pressures, but were judicious on tax cuts and reiterated commitments to public debt sustainability. These budgets barely made a ripple in markets.

There are broader implications of these dynamics for macro policy. The need for fiscal space is one reason that I remain cautious about the likely extent of interest rate increases. Monetary policy will need to accommodate high levels of debt: if government debt servicing costs were to increase markedly, available fiscal space would contract – requiring hard budget choices – and financial stress would accumulate. A form of fiscal dominance seems likely.

Overall, we are moving into a world with a larger role for the state – likely accompanied by higher public debt, higher inflation, and constrained policy rates – in response to political, geopolitical, and economic regime change.

There will be economic and policy turbulence as this change occurs – this week’s UK experience provides a cautionary example. In this world, state capability as well as trust in government and in institutions is of first order importance.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

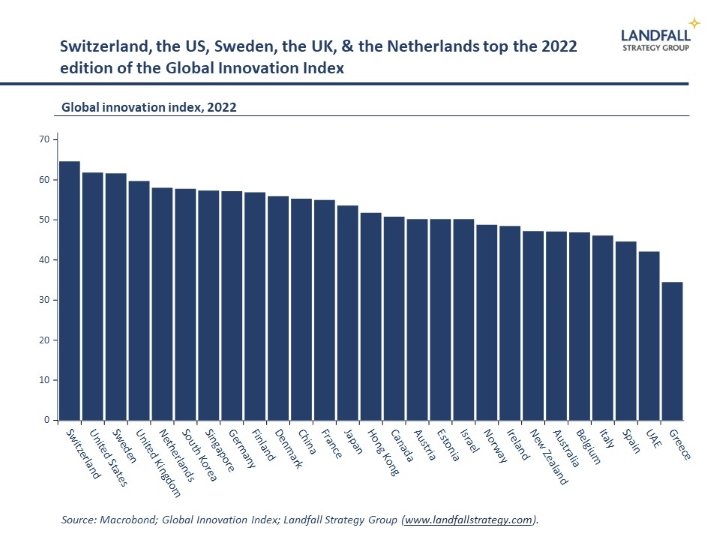

Switzerland, the US, Sweden, the UK, and the Netherlands, topped the 2022 Global Innovation Index, released this week. This is a useful measure of underlying productive potential across economies. The strong performance of many small advanced economies on this measure is instructive. Particularly for small advanced economies, innovation performance is central to developing and sustaining positions of competitive advantage in global markets.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling

https://davidskilling.substack.com