Shifting sands

I have been on the road again, as events and clients begin to return to in-person engagement (hence the 48 hour delay in sending out this note). I wrote this note from a busy Cairo Airport, after 10 days travelling from the Netherlands to London, Dubai, and Aswan.

This note offers some reflections from these different corners of the world, in terms of the near-term trajectory as well as the way in which different countries/regions are responding to a changing global economic and political context.

Multi-speed world

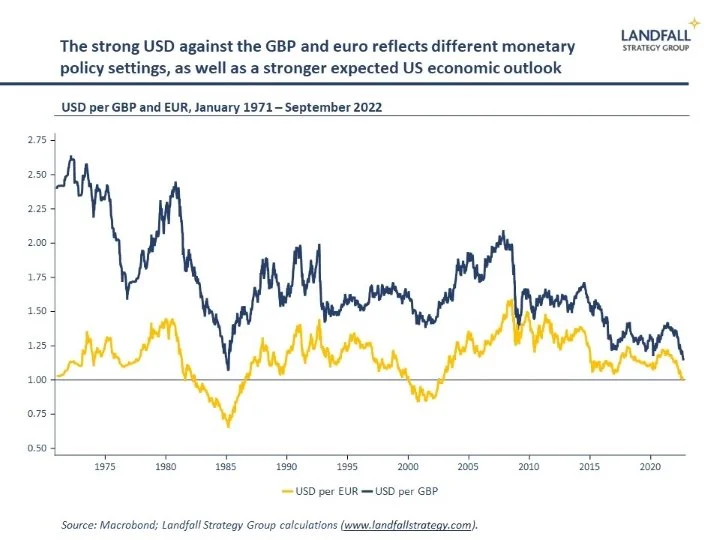

In the immediate term, there is marked variation in the economic outlook. Europe is gloomy, with growth slowing and inflation rising – largely on high energy prices (despite the drop over the past few weeks). These challenges are particularly acute in the UK, with a very demanding agenda for the new Prime Minister. London felt soggy, with the sombre mood reinforced by the Queen’s passing: the economic outlook is subdued, the GBP is at a 35 year low against the USD, and there is little confidence that the new Cabinet has a firm grip.

In contrast, Dubai is buzzy, after a strong Covid performance. Construction and real estate are booming again, and traffic through Dubai Airport is moving close to pre-Covid levels. This is partly bolstered by inflows of Russian people and money. And oil and gas revenues are supporting regional economies.

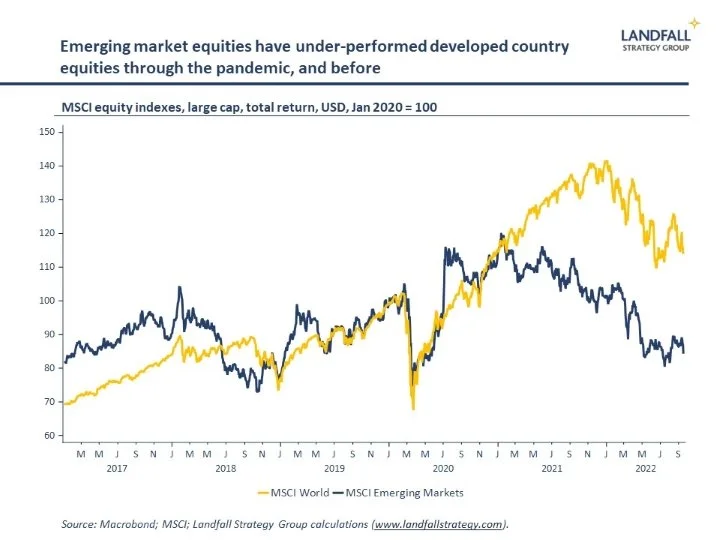

But emerging markets are challenged. Across Africa there are near-term stresses: rising interest rates and a strong USD, capital outflows, and high food prices. This is a reminder of the centrality of the US: the strong USD and higher US interest rates are having an impact worldwide. Even as the US share of global GDP reduces, the US remains the global financial superpower.

On the plus side, in Egypt at least, tourism is returning: planes and hotels are filling up strongly.

Changing global economic geography

Previous notes have discussed a fragmenting global economy, which is more political and regional. Indeed, European Commission President von der Leyen’s State of the Union speech this week talked of the need to reduce the EU’s exposure to Russia and China and to build independence in areas of strategic priority (such as the net zero transition).

Similarly, the US imposed new export controls on technology flows to China this past week, and has recently introduced aggressive financial incentives to locate more of the EV and semiconductor supply chain in the US. And China continues its efforts to build independence in a range of domains – and to reduce its exposure to the West.

These political pressures (friend shoring) will likely reinforce a more regional profile of trade and investment, with the geographic compression of supply chains. Firms are looking to strengthen supply chain resilience (flying over the Suez Canal this week was a reminder of this imperative), as well as to reduce supply chain costs; locating production closer to consumption is one response to these commercial pressures. Geography is back; the world is decidedly not flat. These forces have accelerated through the pandemic and again as a consequence of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

It is those economies/regions that position themselves for the new regime that will likely perform best.

Many East Asian economies performed well over the past several decades, as did many small advanced economies, by positioning themselves for the global economic regime that emerged from the early 1990s. Countries/regions that did not position themselves to capture value and manage risks associated with intense globalisation and new technologies did less well. As the global economy shifts again, adaptation is required.

Dubai also prospered under the globalisation regime of the past few decades, deliberately positioning itself to benefit from global flows of people, capital, goods and services (from Emirates Airlines to Jebel Ali Port). As global flows become more regional and more political, changes will be needed to aspects of this model. Changes can already be seen in terms of its market focus – from Eurasia to Africa.

And as globalisation shifts, new opportunities emerge as well. Africa, for example, can benefit from near-shoring opportunities as some European firms relocate economic activity – as well as by being an important part of the solution for the world’s net zero transition.

These positive examples of positioning highlight the potential costs for post-Brexit UK, which is moving in the wrong strategic direction at exactly the wrong time. In a global economy that is becoming more regional and political, its political unwillingness to engage on Europe – which seems unlikely to change structurally under the new Prime Minister – will come at a growing cost. Over half of the EU27’s trade is intra-EU; it is not possible to escape economic gravity, even for reasonably large economies like the UK.

Geography and geopolitics

‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’, Rufus Miles

Countries are also positioning for new geopolitical realities. Previous notes have discussed the increasing coherence in the West that was catalysed by its response to Russia’s invasion, as well as a hardening of approach on China - although with some geographic variation: note the recent caution of Western-aligned Japan and South Korea on aspects of US semiconductor policy.

But the view from large parts of the global south (Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and many parts of Asia) is very different than from Europe or the US. One marker of this is the pattern of voting at the UN (for example, this week on whether rules should be changed to allow President Zelensky to virtually address the UN General Assembly), as well as imposition of sanctions. Many countries in these regions have abstained, voted against, or have not cast a vote on the resolutions.

There are a multitude of reasons for this. But many countries do not want to get drawn into conflict between the West/US and China/Russia. The preference is to work with all sides. And although being ‘doomed to choose’ is often the reality for countries that are more proximate to these tensions, large parts of the global south have more geopolitical space – and options.

Many Gulf countries are tilting towards Asian markets, including China, and relations with the US are increasingly frosty. Africa is also looking to keep options open: China is an important market and investor in the continent – but there is also value in strengthening the (difficult) ties with Europe and the US.

The fragmentation of the global political order will be messy rather than binary. There will be a Western grouping, a China-led grouping (including a much diminished Russia), and a large group that is in the middle. And the borders to these groupings are likely to be porous.

It was instructive to watch the in-person engagements of the leaders of China, Russia, India and others this past week in Uzbekistan. Mr Modi told Mr Putin directly that war was not the way forward, continuing India’s approach of maintaining independence: it abstained from UN resolutions, is purchasing (discounted) Russian oil, but is not supporting Russia’s invasion.

Sometimes moving away from developed countries provides a sharper perspective on the shifting sands in the global economic and political environment. There will be experimentation and messiness, but it is increasingly clear that global economic geography is shifting and that the geopolitical context is in motion.

Those countries, firms, and investors that best understand and respond to these changes will have an edge over others.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

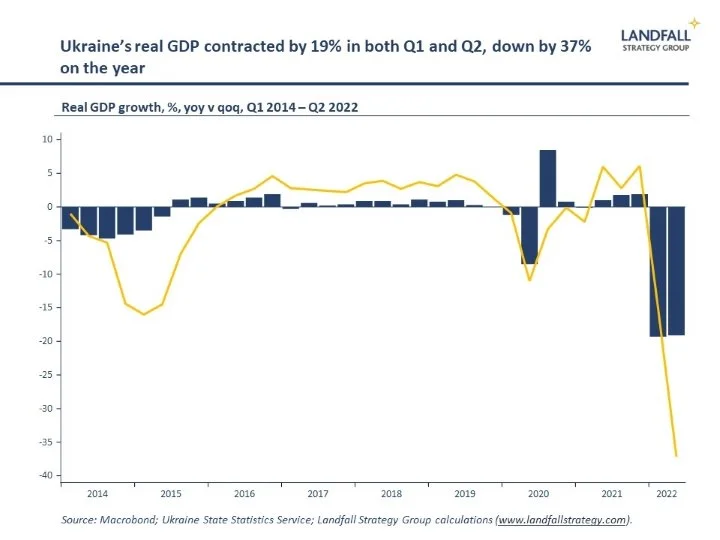

Ukraine is making remarkable progress on the battlefield, breaking through in the north around Kharkiv. The momentum has shifted against the Russians. But the Russian invasion has caused huge, growing damage to the Ukrainian economy. Ukraine’s real GDP has contracted by 19% in both Q1 and Q2, and is down by 37% on the year; and the fiscal deficit may reach 25% of GDP by the end of the year. Substantial financial assistance (and reparations from Russia) will be required.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling

https://davidskilling.substack.com