Mind the gap: firms, governments, & geopolitics

The intersection of governments, firms, and geopolitics continues to be front and centre this week. From the costs of high energy prices in Europe, to the US bans on the sale of advanced semiconductors by Nvidia and AMD to China announced on Wednesday, firms are increasingly in the financial firing line of geopolitics.

This is likely to continue. There has been a marked hardening of (Western-oriented) government attitudes on geopolitical issues over the past few years, reinforced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. After a period of complacency, many Western governments are taking geopolitical realities much more seriously.

The coalition against Russia is still holding despite the economic and political costs. Indeed, the German Foreign Minister argued this week for an additional package of EU sanctions – coming on the heels of visa restrictions on Russian visitors.

This ‘geopolitical awakening’ has reinforced already toughening policy stances on China. The US has strengthened its hawkish stance, on issues from Taiwan to reducing flows of sensitive technology and investment between the US and China. Japan and Taiwan have announced big defence spending increases. And there is a shifting stance in New Zealand, with official encouragement for firms to diversify away from China; and stronger language on Chinese behaviour in the Pacific.

In the UK, Liz Truss has promised to declare China a ‘national threat’ to the UK if (when) she becomes PM. This is partly for domestic political consumption, but also represents an ongoing shift in approach.

And across the EU, governments have become much more assertive on China – putting various economic agreements on ice, implementing tougher FDI screening regimes, introducing human rights legislation, and so on. China is explicitly seen as a strategic rival. And episodes of bilateral tension between European countries and China are on the rise.

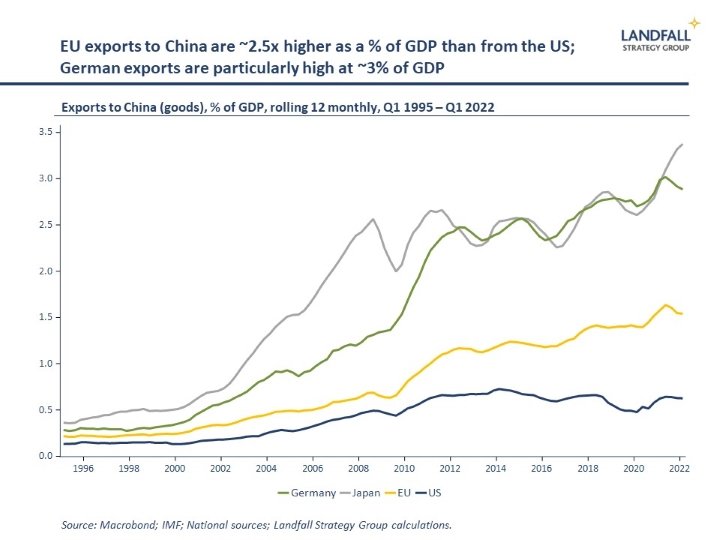

This represents an important change from a period in which Western geopolitical approaches were dominated by economic considerations. For example, the relatively hawkish stance of the US on China relative to Europe was importantly due to its more limited economic engagement. And countries that were economically exposed to Russia (notably Germany) were less inclined to respond forcefully to Russia’s breaches of international law and norms.

These dynamics will remain relevant; there will be ongoing variation in approach between the US and Europe. But there is now greater willingness to absorb economic costs when geopolitical interests are at stake.

Indeed, it is striking that many small economies, such as the Nordics and Baltics, who are deeply exposed to external markets, have tended to be the most active – exactly because they understand the stakes of a weakening of the rules-based system, and the dangers of big power politics.

Whither business?

‘Show me the money!’, Jerry Maguire

But so far, this is largely a government-first approach. Firms have responded less rapidly to changing geopolitical realities.

The Russian invasion led to a mass reduction of operations (or exit) by Western firms from Russia; 1,000 at last count from a Yale University tracker. Firms did this because of the legal requirements of the sanctions; the disruptions to supply chains; or for values-based reasons.

But many Western firms are still active in Russia, or have only gradually reduced business in or with the Russian market; some are taking a ‘wait and see’ approach. Eurozone exports of goods to Russia have fallen by less than half since the invasion; there is still significant export business being reported with Russia.

This is even more true with respect to China. For most Western firms, Russia is a relatively small share of overall income – and the costs of exit are manageable. But the economic scale and centrality of China makes it a different proposition: ~18% of global GDP and ~15% of world exports of goods.

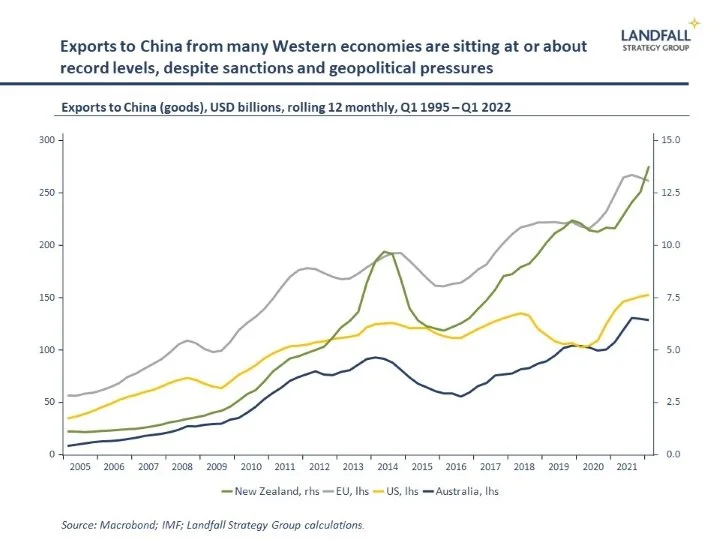

Indeed, it is striking that despite the toughening geopolitical rivalry, exports to China are at or near record levels in economies from the US and EU to Australia and New Zealand. The recent softening of exports is largely due to reduced import demand from China on a weakening economy. And a recent survey from Rhodium Group reported that EU investment into China is at record levels.

Although some firms are diversifying out of China (e.g. Apple into Vietnam), this is as much for commercial reasons rather than in response to geopolitical concerns. There are some firms in sensitive sectors (such as technology) that are different, but at-scale movements out of China are hard to identify. Very few (if any) countries have meaningfully (and deliberately) reduced their export market share to China.

Some of this caution by firms is understandable: there are immediate costs and foregone income from reducing a China presence (and there are few good alternatives); early-movers may weaken their competitive position relative to firms that stay; and there is little pressure from stakeholders. The path of least resistance in the near term may be to maintain the status quo. In periods of uncertainty, keeping options open can make commercial sense.

Mind the gap!

So a gap is opening up between Western government action on geopolitics and the strategic choices being made by firms. This is particularly true with respect to China. But this creates medium-term risks for firms and economies.

Firms need to be careful that they don’t make strategic choices in ways that leave them exposed to changes in the geopolitical environment. A growing array of Western commercial interactions with China will likely be impacted by geopolitical tensions over time, which may require firms to adjust course quickly in response to policy actions by China, the US, and others. Firms that remain highly exposed to these actions are likely to incur financial losses.

And shock events are increasingly likely. Taiwan is perhaps the most obvious risk; a military conflict or economic war would have global consequences, and particularly for firms with a large China exposure. But geopolitical tension are also likely to generate financial costs more broadly: there are increasing examples of sanctions and constraints being imposed on flows in and out of China in response to episodes of bilateral political tension.

More broadly, Western public/consumer preferences are shifting: note the German survey below. Western firms should prepare for growing stakeholder pressure against doing business with geopolitical rivals.

The implication is that firms need to take these geopolitical dynamics seriously. At a minimum, firms need to develop scenarios around geopolitical risk so that they are less likely to be surprised. Beyond this, investing to develop a broader portfolio of options – through diversification and long-term market development – may be a valuable way to manage risks.

The current disconnect between geopolitical risk and economic flows seems hard to sustain. Some firms and investors may be playing a waiting game. But if this geopolitically-driven decoupling is structural – as I assess it to be – waiting to respond may come at a cost, both to firms and to their host economies.

These firm-level commercial decisions aggregate into national-level economic exposures (as Europe is currently discovering with respect to Russian energy). In general governments cannot dictate firm-level decision-making on external markets, but policy-makers need to be thoughtful about the incentives that they create around market concentration and geopolitical risk.

After a period of hyper-globalisation, the global economy is fragmenting with trade and investment flows increasingly shaped by political values and interests. Near-term commercial incentives may make this a gradual process, but firms should be actively preparing for these new realities. Geopolitical risk needs to be on the strategic agenda.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

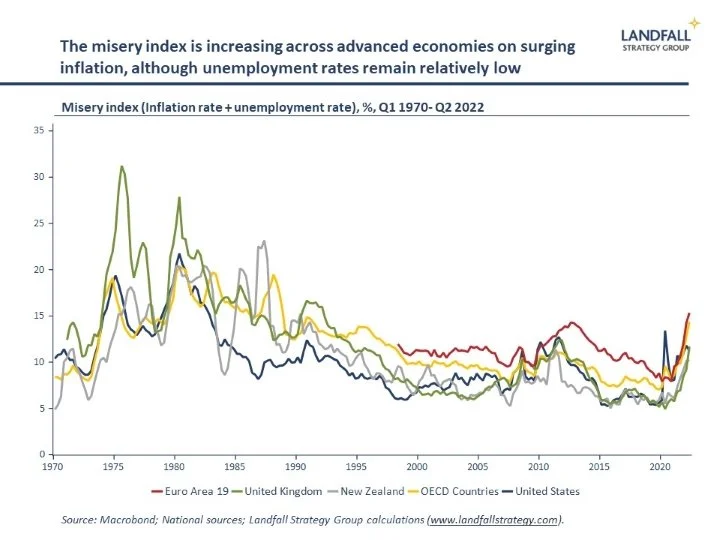

The ‘misery index’ – the sum of inflation rate and unemployment rate – has moved up sharply across advanced economies. It is now sitting at levels at or above those seen during the global financial crisis; and before that last seen in the 1980s and 1990s – although we are still a distance from the 1970s. One key difference from the 1970s is that this increase is driven mainly by surging inflation – with very tight labour markets. Indeed, this week the Eurozone reported both record high inflation (9.1%) and record low unemployment (6.6%).

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling

https://davidskilling.substack.com