The worst & best of times

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, …it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair’, Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

On multiple fronts, the news flow this week has been bleak. Record-breaking droughts and heat continue to hit Europe, the US, and China (and beyond), with rivers at record lows, agricultural yields and energy production in decline, supply chains being further disrupted, as well as higher excess deaths.

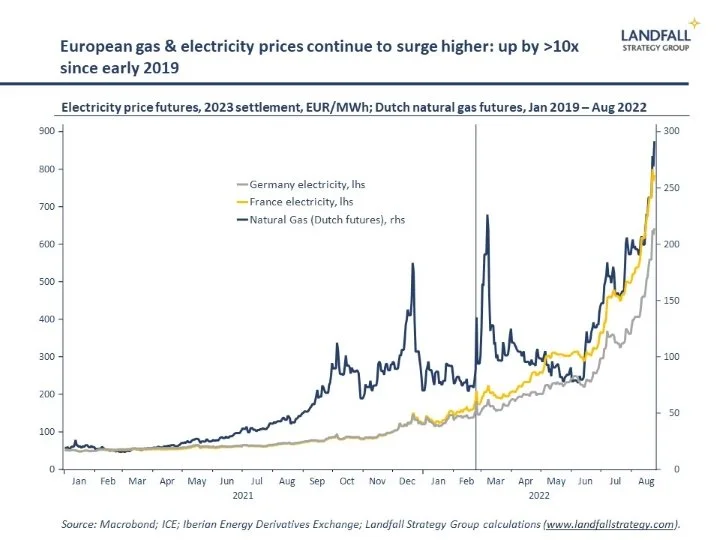

This is contributing to an already-slowing global economy. Part of this is due to surging energy prices, with gas and electricity prices in Europe hitting daily records. A recession in Europe is looking increasingly likely later this year, as industrial production is constrained and household budgets are squeezed.

And inflation is continuing to rise around the world. One striking forecast this week had inflation rising to 18% in the UK. We are likely moving into a new, higher inflation regime: see here, or as Singapore’s Ravi Menon noted this week ‘The era of cheap money, cheap labour and cheap energy is over’.

Partly in response to concerns about faltering growth, equity markets, after a more positive couple of months, weakened again this week. The Chinese economy is looking increasingly shaky. And house prices are beginning to turn in many economies.

On the geopolitical front, the war between Russia and Ukraine grinds on into its 7th month. And tensions continue in East Asia; China’s response to Western visits to Taiwan are contributing to keeping pressures high. Coming on the back of the Covid pandemic, it feels like the world is working through the four horsemen of the apocalypse: Death, Famine, War, and Conquest.

There is domestic political dysfunction in the US; political tensions in China (Covid, property); and looming political challenges in Europe (and elsewhere) as high energy prices bite. And the UK is in all sorts of economic and political trouble, for reasons that extend well beyond Brexit.

Glass half full, glass half empty?

Looking forward, I can (alarmingly) easily develop a list of material things to worry about. It is plausible to make an argument about an unravelling of the system. Mr Macron, in a speech to the first meeting of his new Cabinet this week, talked in sombre language of a ‘great upheaval’ and the ‘end of abundance’.

It is important to take these risks seriously. There has been undue complacency around risks – geopolitical, supply chain, climate, and so on. Governments and firms are now strengthening resilience and actively de-risking on multiple dimensions, having become over-exposed. There is a new economic and political regime, and new approaches are required: a greater measure of paranoia is called for.

But risks can be over-identified: we are much more sensitive to losses/negative surprises than to gains/positive surprises. And firms/countries cannot live (successfully) in a defensive crouch.

A position of excessive risk aversion, where opportunities are ignored, can be costly. Economic and political risks are real and material, but they are not the only dynamics at work. Even in times of disruption and elevated risk, there are opportunities.

‘The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless yet be determined to make them otherwise’, F. Scott Fitzgerald

And it is worth recalling that there have been positive surprises over the past several years as well; for example, the speed with which the world recovered from the pandemic was importantly due to the innovation breakthroughs that enabled the rapid deployment of effective vaccines. Firms and investors that were positioned for this did well.

The roaring 20s?

So let me make the case for a positive structural outlook. This is not to downplay the risks, but to emphasise that there are opportunities. Consider just a few:

First, as I have noted before, globalisation is resilient. Although economic and political factors are generating meaningful changes to prevailing models of globalisation, in ways that make the global system more difficult to navigate, globalisation will continue (albeit in a more fragmented, political, regional manner). Countries and firms can continue to prosper through externally oriented growth models. Indeed, global trade flows have been resilient through the pandemic despite initial concerns.

Economic and geopolitical factors will reshape trade and investment flows, the design of supply chains, and so on. But there are also opportunities here: Vietnam is becoming home to more of Apple’s production that is shifting out of China; Singapore is receiving flows of people, firms, and capital from Hong Kong, China, and elsewhere; and there are growing opportunities for economies (from Africa to eastern Europe) that are proximate to large consumer markets. And there are some new pockets of strong growth, notably around digital trade.

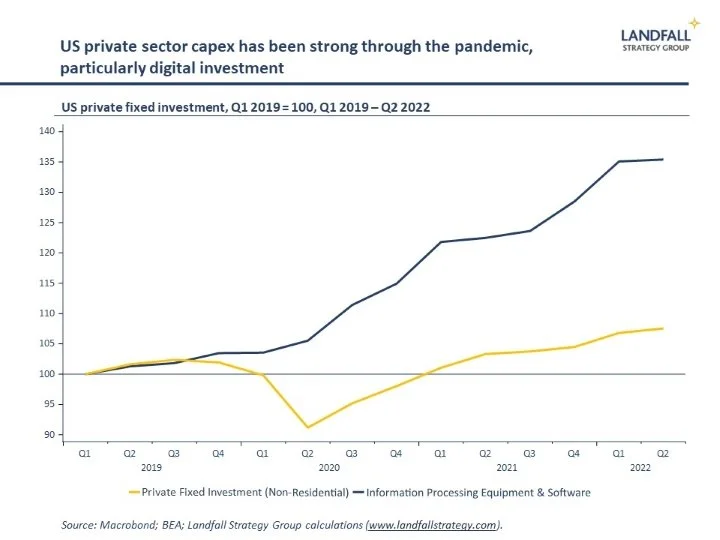

Second, firms are investing behind new business models (automation, digital transformation) as well as in new areas of technology. Capex by US-listed companies continues to be strong, with healthy investment intentions – particularly in technology sectors. Some of this investment behind innovation and technology was accelerated by the pandemic.

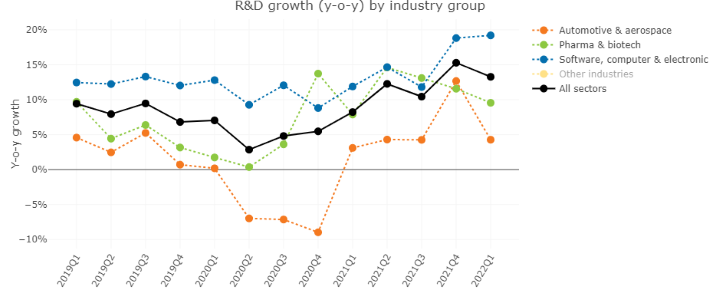

And across advanced economies, as well as China, industrial policy around key areas of technology is picking up markedly – notably semiconductors, but extending into a broad range of other areas. Public sector R&D is being increased in the US and elsewhere (note the recently-passed CHIPS and Science Act). The OECD report resilient and strengthening private sector R&D spending growth. And the pace of innovation in areas from quantum computing to AI is accelerating.

This innovation, and the associated investment, creates the potential for sustained higher rates of productivity growth – a productivity renaissance. The tight labour markets in the post-Covid economies may strengthen these incentives further.

And third, there are opportunities in the net zero transition – which will involve fundamental changes in energy, transport, and industrial systems. The deployment of renewables is picking up pace. From the US to Europe and China, substantial investments are being made in reducing emissions. The EU Recovery Package had a strong emphasis on green initiatives, and recent US legislation has put more public funding behind the transition. The speed of this transition is likely to be further accelerated by the current energy crisis, as well as the growing evidence of rapid climate change.

The Netherlands is a good example, with last year’s coalition agreement committing the government to allocate €35 billion to the net zero transition: from investment in renewables to retrofitting parts of the domestic gas network for hydrogen. And there is rapid private sector innovation in food and agriculture, transport, and other sectors.

Walking and chewing gum at the same time

Periods of disruptive change often lead to innovation. The 1970s led to new institutions, new technologies, new growth firms. There were new risks to be managed, but also opportunities to invest behind.

Small advanced economies are deeply exposed to these global economic and political dynamics, and face strong competitive pressures to respond. As is often the case, Singapore provides a useful illustration. PM Lee’s National Rally Day speech this week struck a balance between risk and opportunity – acknowledging the many economic and political risks facing Singapore, while pushing ahead with the massive Terminal 5 at Changi Airport, the world’s largest fully automated port at Tuas, and various other initiatives to position Singapore for new opportunities.

Risks do need to be managed in ways that they have not been, but there is also a case for investing in opportunities with strategic intent.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

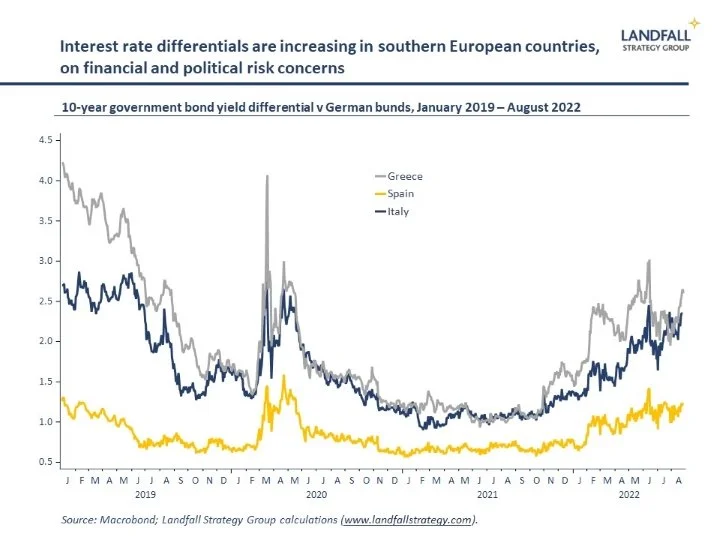

Financial pressures are building in the Eurozone, due to interest rate normalisation as well as political risks in Italy – despite the ECB’s ‘anti-fragmentation’ initiatives. The yield differential of several southern European government bonds to German bunds has widened over the past year – with PM Draghi’s imminent departure a factor in Italian debt markets. The rising interest rates will weigh on these economies because of high government debt stocks: ~150% of GDP in Italy and ~200% of GDP in Greece in 2021.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling

https://davidskilling.substack.com