David, Goliath, & winning in the new global economy

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is now over five months old, an invasion that was initially expected – by the Russians and to an extent by Western intelligence – to take just a few days. Given Russia’s overwhelming military advantage on paper (>10x difference in military spending), this initial assessment was not surprising.

But superior Ukrainian tactics, creativity and bravery, together with Russian incompetence, held the invasion at bay. And now bolstered with Western arms and other assistance, Ukraine has continued to out-perform – fighting the Russians to a de facto stalemate, at least for now.

This has come at an enormous economic and human cost in Ukraine, but it has been a remarkable performance. Although the outlook on the battlefield remains uncertain, with different assessments made of how the momentum is likely to shift over time, Ukraine has a realistic chance of ending this conflict in a reasonable position. And irrespective of how this ends militarily, Russia has been deeply damaged: its strategic position and economic potential have been structurally compromised.

This experience is not unique to Ukraine. Large powers have an imperfect record of successful invasions, from Vietnam to Afghanistan. And through history, academic research shows that small states can beat more powerful states – under certain conditions. An academic study of ~200 conflicts over the past two centuries found that, although large powers tended to beat smaller powers (by ~2:1), this relationship was inverted when small powers adopted innovative tactics (e.g. asymmetric war techniques, such as guerrilla warfare).

In short, the Davids of the world can beat the Goliaths when they adopt different approaches – the scale advantage can be diluted (or reversed) through innovation and creativity. It is sometimes better to be nimble and agile than to have the raw power of a towering giant.

But small powers need to take deliberate action to reverse the surface disadvantage; seriousness is required as well as agility. Indeed, many small states in exposed positions invest heavily in military capability, total defence, and so on (from Finland and the Baltics to Greece and Singapore).

‘In a world where the big fish eat small fish and the small fish eat shrimps, Singapore must become a poisonous shrimp’, Lee Kuan Yew

War by other means

This relationship between scale and performance can be seen in other domains. For example, it is commonly assumed that small economies are disadvantaged relative to large economies: they have smaller domestic markets, fewer resources, are more exposed to external shocks, and so on. But as regular readers will know, this turns out not to be the case.

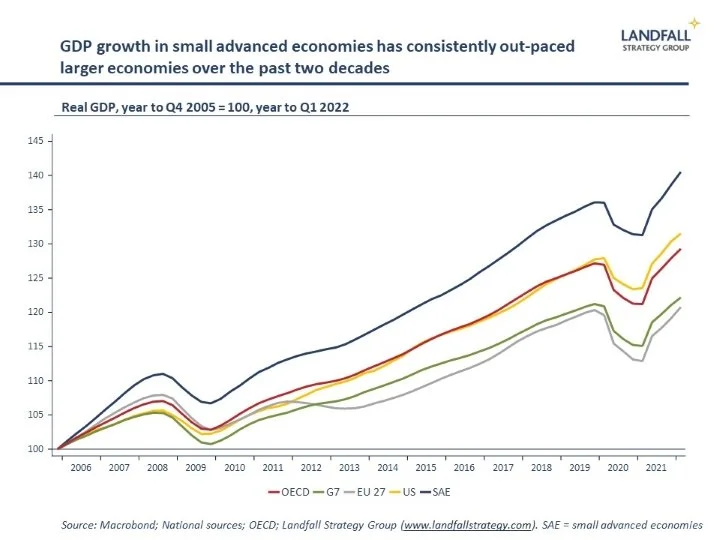

Many obituaries have been written for the small economy model over the past 15 years, commonly after economic shocks like the global financial crisis or due to concerns about the outlook for globalisation. But small advanced economies have continued to consistently out-perform their larger counterparts: they have generated stronger growth through the pandemic (as well as strong health outcomes); over the period since the global financial crisis; as well as over the past several decades.

Although small economies have benefited from a supportive international economic and political environment, the primary reason for small economy success is high quality policy settings – from skills and innovation to macro policy and infrastructure – with a high degree of strategic coherence, supported by effective, agile state institutions.

Being exposed to competitive pressures can be uncomfortable but the imperative to compete in global markets provides a sharpness to small economy actions. For example, small economies have managed the impact of globalisation and technology better than larger economies, designing policy to deliver good outcomes and to retain public support. And small economies produce a disproportionate number of successful, competitive multinational firms.

‘We haven't got the money, so we'll have to think’, Lord Rutherford (New Zealand Nobel Laureate).

However, small economies also have limited margin for error. There are multiple examples of small economies that have encountered difficulties, such as Greece and Ireland, after policy mis-steps. And the increasing frequency of idiosyncratic shocks in the post-Covid world will place particular challenges on small economies given their relatively high sectoral concentration levels.

Agility and responsiveness, as well as resilience and an ability to innovate, will be increasingly important attributes of national economic success. Many small economies are well positioned for this.

Diseconomies of scale?

Neither are the effects of scale on outcomes deterministic elsewhere. Consider just a few examples.

Geopolitics is increasingly shaped by big power rivalry, and smaller states can be collateral damage in an increasingly non-rules based world. But smaller countries also have an ability to stay out of the way. It was the direct protagonists in the US/China trade wars that suffered the biggest losses. And although China often squeezes other economies that it has disputes with, this is as often with larger economies (Japan, South Korea) as small economies (Lithuania, Norway).

Large economies can advance their interests through raw power; but that doesn’t always deliver good outcomes. Creative, agile diplomacy can allow smaller states to manage their exposures and to continue to prosper (Singapore, Switzerland).

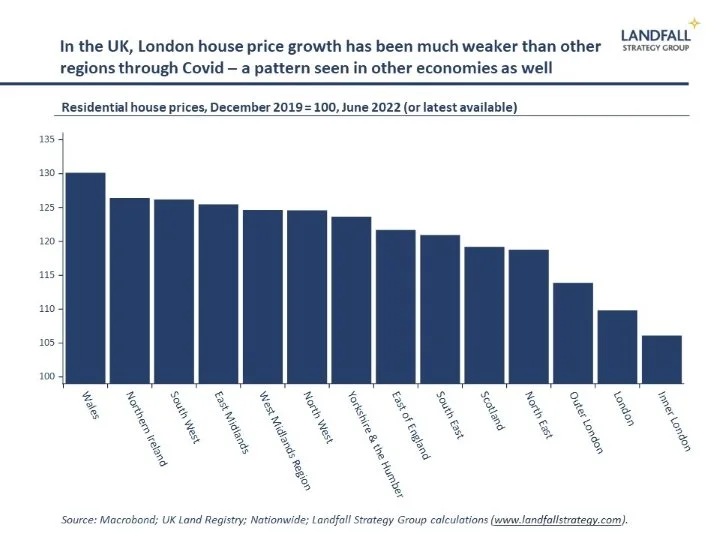

In another domain, there are shifts in economic geography in the post-Covid world – with some evidence of people/firms relocating away from large hubs (New York, San Francisco, London) to smaller cities or regions. The use of technology during the pandemic, coupled with shifting preferences, has loosened the hold of large cities.

Population growth shows this, as does variation in patterns of house prices/rentals in a number of advanced economies from Japan to Canada, the US and the UK. Large cities will remain important, but agglomeration forces are likely to weaken.

In terms of firms, the empirical evidence suggests a positive relationship between firm scale and productivity, exporting, capital intensity, and so on. And numerous studies find that industry concentration has increased, with a smaller number of large firms dominating areas of the economy and earning economic rents. There is a winner take all dynamic, particularly in the technology space (Amazon, Google, and others).

However, many of these now-large firms are young, and either created new industries or displaced incumbents. During the pandemic, new firms like Moderna and BioNTech were central to successful Covid vaccines. Scale has been a function of success, not the other way around.

Creative destruction in the listed company space remains high, and start-up rates and IPOs are also healthy. Over the past decade, substantial amounts of venture capital has gone into funding the next big thing in Silicon Valley and beyond (note a good book by Sebastian Mallaby on the VC industry). Some of this has been juiced by low interest rates over the past decade, but the point remains that small, young firms remain an important source of economic dynamism.

So for all of the plausible talk of the advantages of scale (US, China, Amazon, etc), success does not necessarily belong to the large.

Survival of the fittest

We are likely to be moving into a period of elevated economic and political volatility. Scale is a useful lens to think about which countries and institutions are most likely to prosper in this environment.

‘It is not the strongest or the most intelligent who will survive but those who can best manage change’, Charles Darwin

Scale can buffer against shocks, but can also make change more difficult. Smaller states and firms, which are deeply exposed to external dynamics, are often well-positioned to respond to these changes – they sense change quickly, have agile decision-making, and often have helpful levels of paranoia about the competitive environment.

Even after the destruction wreaked on Ukraine, I would put my money on Ukraine’s long term performance over Russia. And more broadly, I expect disproportionately strong performance from smaller economies.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

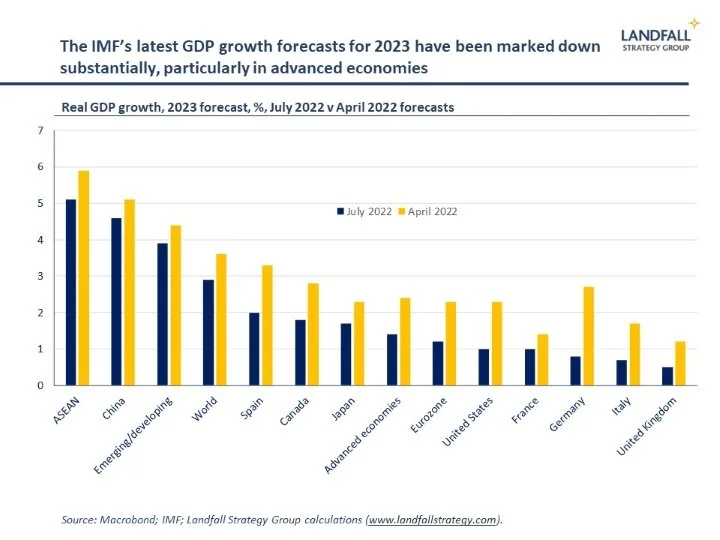

The IMF released its latest World Economic Outlook update during the week. Forecast GDP growth for 2022 and 2023 was marked down substantially from the IMF’s previous set of forecasts in April. World GDP growth for 2023 was downgraded by 0.7% to 2.9% - and advanced economy GDP growth was marked down by 1.0% to 1.4%. Germany and the US saw particularly large downgrades. And the IMF note that ‘the risks to the outlook are overwhelmingly tilted to the downside’.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling